Slavery marks an important era in the history of the United States, one that is often discussed in terms of numbers and dates, human rights abuses, and its lasting impact on society. To be sure, these are all important aspects to understand, but one thing that is often given relatively short shrift is what it was like to actually be a slave. What were the sensory experiences of slaves on a daily basis? How can we dig deeper into understanding the lives of slaves and understand the institution as a whole?

Guest Daina Ramey Berry has given this question serious thought. In this episode, she discusses teaching the “senses of slavery,” a teaching tool that taps into the senses in order to connect to one of the most important eras in US history and bring it to the present.

Guests

Daina Ramey BerryOliver H. Radkey Regents Professor in History at the University of Texas at Austin

Daina Ramey BerryOliver H. Radkey Regents Professor in History at the University of Texas at Austin Leslie HarrisAssociate Professor of History at Emory University in Atlanta

Leslie HarrisAssociate Professor of History at Emory University in Atlanta

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Why don’t you start off by telling us what you mean by the “Senses of Slavery,” and how you use it?

A lot of times when I say senses, people think I’m talking about the census, the enumeration of counting people, but I’m actually talking about our senses—the touch, sight, sound, smell, and feel. It’s a pedagogy I’ve created over the years on how to teach slavery in a way where students can really tap into understanding the institution. By tapping into their senses, I’ve found that they were able to connect to a history that is horrific to some, embarrassing to others, painful, it angered some folks, or they felt “Oh, it was too long ago, I can’t really understand what happened then.” By tapping in to their senses, I brought it to the present. That’s one of the reasons why I use this in my teaching.

Well let’s start with some examples. What about the sense of touch? How do you connect our own sense of touch with slavery?

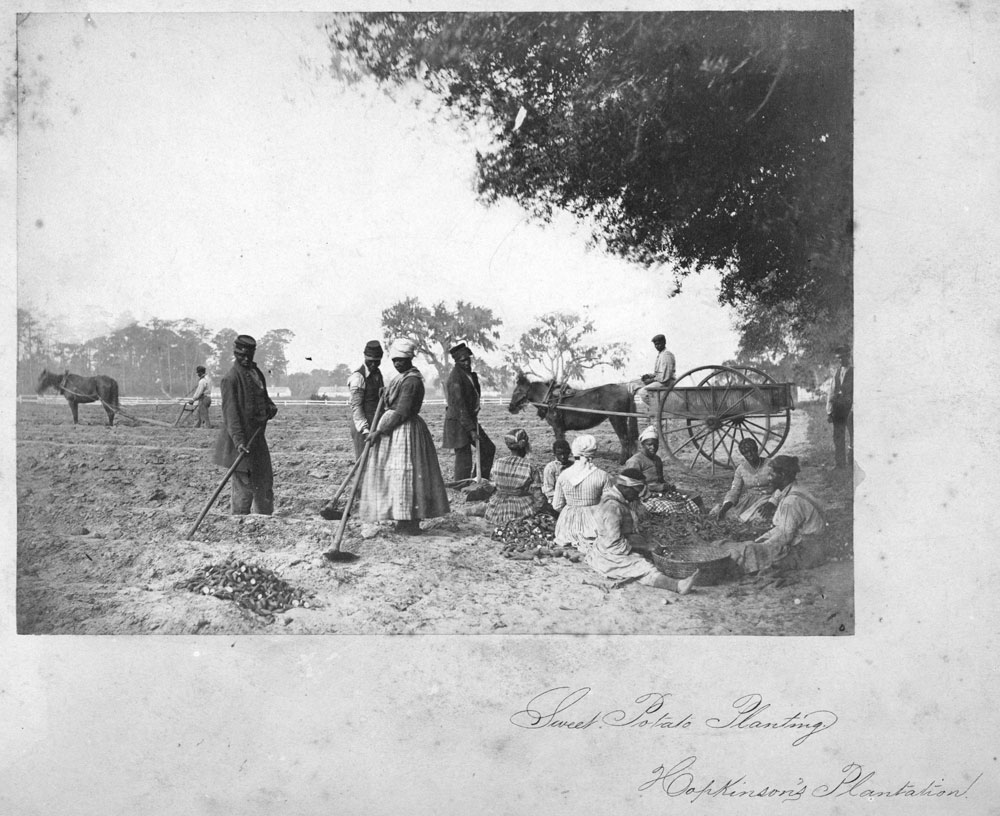

One of the things I do is I bring in cotton. When people think about slavery in the United States, they often think of these large cotton plantations. I’ll bring in cotton or I’ll tell the students, if I’m dealing with a younger group of kids I’ll tell them to bring cotton to school. I don’t tell them what kind. Some of them will bring in a tee shirt, some might bring in some cotton balls or a Q-tip or something, and then we’ll talk about what it feels like. Then I’ll bring in raw cotton. I have these cotton kits that show all the different stages of cotton production, from when it’s in the boll and they have to take it out and find the seed that’s in there, the leaves, the dirt. So they’re really getting a sensory sense of that touch. I’ve also brought in rice and had them shine rice with a mortar and a pestle, where they’re actually pounding the rice to see how it changes. They’re also using their sight because they’re seeing how it shines. Also we look at tobacco and tobacco leaves and raw sugar. So I bring in all the types of crops that enslaved people worked on and then we do a lesson on slave labor, but they’re also touching and feeling and understanding the crop they worked with.

So you can go from touching the actual things that slaves touched as they were working to a lesson about what that work was like?

Exactly

You can see how that would work with students of a lot of different ages. What about sight?

It’s funny, we’re talking about these separately, but I actually try to bring them in all at the same time. So on a lecture on labor, if they’re touching the cotton, I’ll bring in images of former slaves picking cotton or field photographs, which is difficult because we don’t have that many photographs. We have a lot of them from the late 19th century, after slavery was over, and these were former slaves picking cotton. We also have those taken during the Civil War. We have some images of slaves. We also have a lot of sketches, and I’ll bring some of those in. We’ll also look at videos, the videos with still photographs and scholars, the PBS specials where they’ve done reenactments. When I was teaching at another institution there was a cotton field not far so one of my classes went (this was a college class) and picked cotton. The students got to see what it felt like, and imagined what it would be like for twelve to fifteen to eighteen hours a day. Giving them ways to make them — to see slavery. What kind of things would enslave people have seen? What do the cabins look like? What do the fields look like?

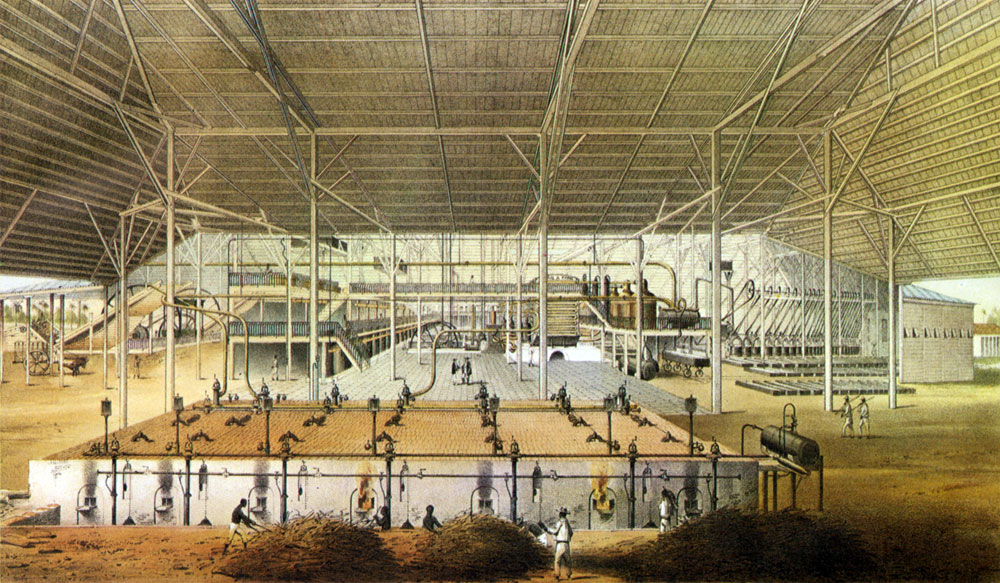

Also, looking at urban forms of slavery, if you’re in a factory—they were brick making—I would bring in a brick. They’d say, “Oh, I didn’t know slaves worked in factories.” Or coal. So I’d make sure they’d see and feel all the different products that enslaved people produced.

It is really interesting just hearing you talk about it, bringing in a brick or touching cotton really brings something to life in a way. What about taste? Do you get to feed them?

Actually, I make that a project for my classes. Not every semester, but I’ve done that. One of my group projects was on slave nutrition and health. They looked at enslaved diets. We looked at the kind of foods that plantation records showed that they ate: salt pork, cornbread, hominy. We also look at different recipes. One time we did a full sensory discussion/experiment where we were actually eating the cornbread based on a recipe we found. We tried some okra and collard greens. It was really kind of neat and the students enjoyed that while we learned about diet, health, and nutrition. We looked at the calorie intake; how many calories are they burning, picking cotton or working in a rice field for that long. We were looking for the imbalance, and that explained some of the health issues we had read about. It really allowed them to connect in ways that they hadn’t necessarily thought about.

So then do you connect taste with smell?

Absolutely. Smell actually was hard for me at first, when I first started doing this. I would bring in liquid smoke. The only reason I knew about liquid smoke was my grandmother used to use it in her collard greens.  Instead of putting in pork, she would put in liquid smoke, and my mother did too. So I would bring that in because often times in the fields, in the early part of the season, in January through March, when they were preparing the fields, enslaved people would have to burn the crops from the previous year. So often, for those that live in the south, you’ll drive through and you’ll see different parts of the crops being burned as they’re preparing the fields for the following planting season. So I’d bring in that as the smell, but I’d also have them smell raw tobacco and cotton, I’d bring in raw forms of that. I’d bring in the oil version of cottonseeds. Those are some of the things we’d use for smell. We’d also smell the foods. That was another way to connect the students to the work.

Instead of putting in pork, she would put in liquid smoke, and my mother did too. So I would bring that in because often times in the fields, in the early part of the season, in January through March, when they were preparing the fields, enslaved people would have to burn the crops from the previous year. So often, for those that live in the south, you’ll drive through and you’ll see different parts of the crops being burned as they’re preparing the fields for the following planting season. So I’d bring in that as the smell, but I’d also have them smell raw tobacco and cotton, I’d bring in raw forms of that. I’d bring in the oil version of cottonseeds. Those are some of the things we’d use for smell. We’d also smell the foods. That was another way to connect the students to the work.

And finally, what about hearing? What about sound?

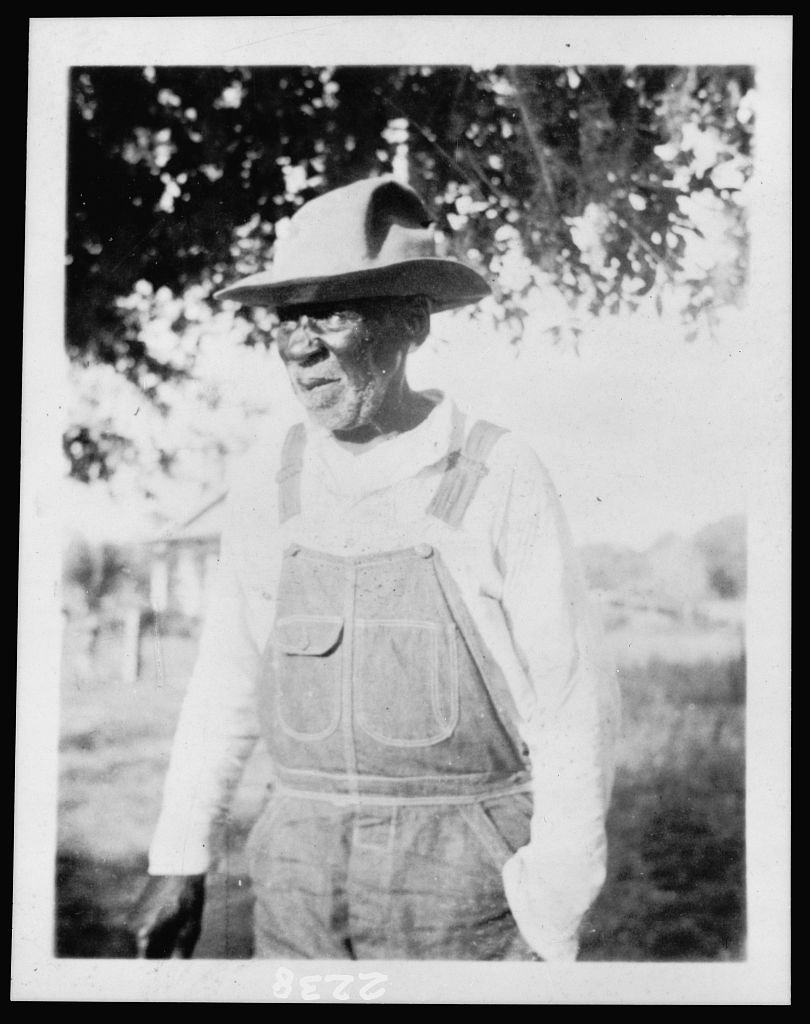

That actually was a lot easier than I thought, primarily because enslaved people sang work songs when they were working in the fields. They sang spiritual songs in church services, whether they were at praise meetings or by a tree or in an organized church setting. I would play slave spirituals. These are accessible now through the Library of Congress, the Voices from the Days of Slavery. There are a number of songs on their website, you can listen to former slaves actually singing the songs they sang during slavery. One of my favorites is by an enslaved man named Wallace Quarterman, and he was enslaved on Saint Simons Island, Georgia, and he sang a song called Jesus is a Rock in a Weary Land.

[Jesus is a Rock in a Weary Land plays]. Interview with Wallace Quarterman, Fort Frederica, St. Simons Island, Georgia (Gullah), June 1935. Library of Congress, American Memory Project, Voices from the Days of Slavery Collection.

That’s very moving. How do your students respond to these songs? Do they seem familiar in some ways? Completely unfamiliar?

What I’ll do is (if we’re doing music for the day) I’ll bring in songs that they may have heard of in their own church congregation. Then I’ll bring in songs that they may have not heard at all. I also bring in the lyrics, which is the sight part. So they actually read the words of the songs. They can talk the hidden meanings. We analyze the lyrics, we think about what they might have been saying, what hidden messages, why they might have chose to sing that song. When they hear the audio files, like the one we just listened to, they’re always amazed at their [the slaves’] voices. They’re embedded within the slave narratives, which are also on the Library of Congress website. They’ll hear them talking and say, “the slaves don’t sound angry; they don’t sound bitter, they’re talking about praying for people.” And then they hear their prayers and they hear their songs and it allows them to feel a sense of closeness to the group of people who we’re studying. Just reading words on a page is so flat. It seems very flat and not multi-dimensional, like it is to hear the song, to read the words and then look at the photograph of the person who was singing. That’s right there tapping into three or four of the senses that we’ve already discovered.

It’s seems that putting all these senses together, all these aspects of everyday life, helps students relate to slaves as familiar human beings. They worked, they cooked, they sang and danced together, and really this is something that all historians try to do, to see the past as both familiar and different. But that also seems to normalize slavery in a way. How do you use the senses to bridge the normality of everyday life with the degradation and violence that were also a part of everyday lives of enslaved peoples?

That’s a really good question, and it is something that I deal with every time I teach. Partly because students are looking for a place to enter, and so by giving them music and song and things that are familiar they can enter into this conversation about slavery in a way that they’re comfortable. But they also sometimes want to distance themselves when they hear about the brutality, or they don’t want to look at it or they don’t want to have to think about it because it’s so hard to hear. The stories that are told or the descriptions that we have of brutal whippings and beatings, children having to whip their parents or husbands witnessing whippings of their wives or vice versa or remembering the sound of their mother’s cry after they were separated at the auction block. It’s tough to balance that, but one of the ways I try to is to show the diversity of slavery and talk about how one person may not have ever been sold, they may have stayed in the same plantation their entire lives, while other people could have changed hands four or five times. When I talk about the stories or we’re reading the narratives where enslaved people were describing brutality, whippings, and all kinds of violence, but there are others that rarely saw or experienced that. By allowing students to understand that this was a very diverse institution depending on where you lived, what kind of crop you produced, the attitude of your owner was key to an enslaved person’s experience. The number of slaves on the plantation, the number of family members that were present, biological or fictive, all of that mattered. By remembering that, when we talk about song and dance and music and food, those are just coping mechanisms, because these were just human beings and they had to live.

Do you find that talking about these sort-of everyday experiences actually helps students or hinders students when they are actually confronted with the violence of slavery?

Absolutely. I did an experiment this past fall with my undergraduate class here at the University of Texas and I brought the students to see 12 Years a Slave. I teach all my classes with the senses in mind, even when they do presentations they have to think about trying to tap in to two or three of the senses in their course presentations, and if they can get all five then I’ve done my job. Anyways, we went to the screening of the film and I knew I would be able to get them to feel, they would get the sense of touch because they would be emotionally moved by the film (I had already seen it), the sight of what they would see—a lot of people say, when they’ve seen videos or movies on slavery, but they’ve never had that kind of imagination. They might have read it, but what they imagined wasn’t the same as what they see on screen. So the sight part is very powerful. In that film the music, and the spirituals, Roll Jordan Roll is played in there. It’s a very powerful song, and it builds. They didn’t smell things in the theater, but the students were overwhelmed. They came out of the theater, they loved the movie, but they came out emotionally exhausted. They said, “Dr. Barry, we felt everything.” They were at a theater where they could have food, and some of them said, “I couldn’t eat because I was so overwhelmed by the sights, the sound, and everything else. All of my other senses were in such high gear that I couldn’t finish the food that I had ordered.”

I felt like, on the one hand they really understood it and were able to connect with it in a way that just me telling them about the book, 12 Years a Slave, or having them just read it wouldn’t have been the same.

Sounds like they were really prepared for the whole experience in a way that they could take in all the senses. They could take in so much more information by being prepared the way that you prepared them. You use this with younger kids too. Tell us a little about using it with people of different ages.

Well, I have taught the Senses of Slavery from kindergarteners up to senior citizens. I’ve given lectures at senior citizen facilities, or lifelong educational programs, and it works across the whole span. I just recently did a cotton exercise with some ten year olds, a fifth grade class. I was amazed at how well they understood the complexity and the diversity of the institution of slavery. They understood slavery because I gave them the tools to think about slavery in an empowering and honest way. It was something that they could access. They were dancing at the end of class, doing the work songs, imagining picking cotton. But it wasn’t like doom and gloom, this is so depressing or so sad, and it wasn’t necessarily celebratory. It was a way to enter in to slavery that wasn’t so frightening to ten year olds. I think they really got it.

Related Episodes

- Episode 105: Slavery and Abolition

- Episode 120: Slave-Owning Women in the Antebellum U.S.

- Episode 54: Urban Slavery in the Antebellum United States

- Episode 6: Effects of the Atlantic Slave Trade on the Americas

- Episode 88: The Search for Family Lost in Slavery

- Episode 114: Slavery in Indian Territory

- Episode 21: Causes of the U.S. Civil War (part 1)

- Episode 22: Causes of the U.S. Civil War (Part 2)

- Episode 41: The Myth of Race in America