In 7th century Arabia, the Islamic community was nearly torn apart by a civil war over the assassination of the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (d. 656), and the accession to the caliphate of Muhammad’s adopted son Ali, supported by Uthman’s assassins. The events of the first fitna, as it is known, are often portrayed as a struggle over the right to rule the Islamic community, but it was much more—a power struggle between Muhammad’s wife Aisha and Ali, and a dispute over who had the right to avenge the murder of Uthman.

In picking up where Episode 57 left off, guest Shahrzad Ahmadi describes this tragic turn of events that sent shockwaves through the nascent Islamic community, and that continue to reverberate today.

Guests

Shaherzad AhmadiAssistant Professor of History, St. Thomas University

Shaherzad AhmadiAssistant Professor of History, St. Thomas University

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

This is the second of a series of episodes we’re doing on the origins of sectarianism in early Islam.

If you missed our last episode, we ended with the death of the third caliph, Uthman in the city of Medina in the year 656. Ali, who is the prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law, adopted son and cousin has been declared the caliph. This is not sitting well with two of his remaining companions, men by the name of Zubayr and Talhah, nor with his favorite wife, Aisha. So let’s pick up the story there.

You had mentioned how Ali and Aisha hadn’t had a great relationship. Does that contribute to this situation?

Some say it does, but agaiin I think it is oversimplifying two very complicated figures. I don’t think that Aisha would have led a war simply because she did not like Ali. But certainly his character had been in question for her for some time. She had been accused of infidelity when she was married to the Prophet and the Prophet was very, very hurt by the whole fiasco and really at the brink of indecision. He simply didn’t know what to do about the situation.

He went to Ali to ask for advice and Ali basically says, ‘Women are replaceable, this is becoming complicated, just get rid of her.’ And Aisha never forgives him for this—not only not siding with her, but encourage Muhammad to divorce her. And the two of them really hadn’t been on the best terms since then. But again, it would be too simple to say that she didn’t support him because of this one incident.

Right. As we mentioned at the end of the last episode, one of the more immediate causes of the disagreement was that Ali’s claim to the caliphate had been supported by the very people who had assassinated the previous caliph, which was also considered quite controversial.

Exactly. And she considered herself the Mother of the Believers. I think the other wives of the prophet were not politically active because they had very strong male figures in their lives who prevented them from being politically active. She did not have those things. Her father was dead at that point, she had a brother who actually sided with Ali, and she didn’t have anybody restricting her. She was pretty free in that respect. So she was able to exert some authority over the Islamic community and she believed it to be her right to do so.

What is the fallout of this disagreement? You mentioned that not everyone supported Ali as caliph. What actually happened as the community tried to sort this out?

Zubair and Talhah actually originally swear allegiance to him. There’s a lot of discussion that this was by force, that they felt really intimidated and pressured to do so. And, in fact they eventually defect and go to Aisha’s side and say that he shouldn’t be the caliph. And of course this is also politically motivated. They were the other two companions left. They probably also wanted that political power for themselves in some way. And Talhah and Zubayr were also Aisha’s cousins, so there’s that allegiance as well. Aisha and Talhah and Zabayr organize to fight against Ali.

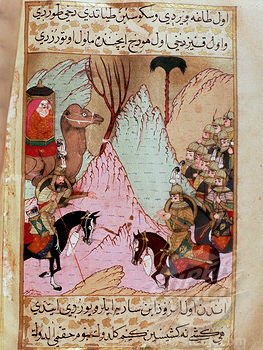

There’s an epic battle that takes place in Basra, it’s called the Battle of the Camel. The camel actually refers to Aisha. It’s a way of talking about her without directly referring to her. She is sitting in a howdah, which is sort of like a carriage, on the camel and she’s the one figure that’s situated on this camel to which the battle of the Camel refers.

So she’s visible to the entire battlefield. Is she the one who rallied the troops to battle?

Absolutely. She’s a really fascinating and powerful woman.

Zubayr and Talhah are dead by noon. It’s a very bloody war and an incredibly dramatic event for the Islamic community. There are hadiths narrating that this is an incredibly violent gruesome battle, and especially for a community that had not experienced this kind of bloodletting before. There’s so many scenes described in histories of limbs flying and people dying—and here is this woman on a camel that’s been pierced with so many arrows that people describe it as a hedgehog. It’s just been attacked to no avail because she doesn’t get actually injured. But it really is an incredible moment in Islamic history. Here’s a woman, sitting in the howdah, directing men to fight battle. And there wasn’t a pre-Islamic tradition to this. Women had traditionally been present on the field of battle. They would encourage men to fight. But to be essentially a general on the field, it’s an incredible thing.

So this is, as you mentioned, a really traumatic event. It’s 656, which means it’s barely twenty-five years since the prophet Muhammad died, and the community is literally tearing itself apart, which is, of course, antithetical to the notion of the unity of the community. So how does the battle end? You’ve mentioned a lot of bloodshed. What is the outcome?

Like I said, Talhah and Zubayr die pretty early on. Aisha remains unhurt, but they do surrender. So Aisha’s side loses. The legs of her camel are actually cut out from under her and her half-brother, who’s fighting for Ali, comes to the howdah and opens it up and calls her by the prophet’s nickname for her, a sort of sneering attack. And people are really angry with the Mother of Believers. They’re angry about the death and bloodshed. Ali is actually really respectful of her. He puts her in comfortable lodging and promptly sends her back to Medina and says, ‘Stay there and don’t be involved in politics.’

And she ends up being a very important figure for hadith literature. She narrates a lot of hadiths. So we have a lot of stories from the prophet and stories from the era narrated back to Aisha. And that makes her very important for the Islamic community because we have a history from her.

So what happens with Ali then?

So, Ali can’t catch a break. After he defeats Aisha, he has to continue the civil war. After all, Uthman had been killed, and the people who killed him were never reprimanded. This had to be addressed at some point. So in 657 there is another civil war continuation of this in Siffin.

Mu’awiyah, who is the relative of Uthman—he’s from the same clan as Uthman—says that he’s responsible to revenge Uthman’s death. The way that murders were addressed in this period was the person who was killed was the responsibility of one’s clan or ones relative. So not anybody could go and kill the murderer of that person. Someone associated with the deceased would then address the issue. The proper person to address the issue of the death of Uthman was Mu’awiyah, and not Aisha. And so many of the people who criticized Aisha said this. They said, ‘Look, you’re not the person to be reprimanding Ali for anything.’ She would say, ‘No, I am the Mother of believers, and Uthman was a believer, therefore he is relevant to me.’ But in terms of Arab tradition it was actually Mu’awiyah. He wants also to take over the caliphate. He’s also a contender politically. And Ali does not want a long, drawn out war. It’s really in his best interest to negotiate with Mu’awiyah.

So is the responsibility for Uthman’s death really shifted to Ali at this point? One of the things we’ve noticed is that we have a lot of names, but we’re not discussing the names of the actual assassins themselves. So is he sort of taken on by proxy the role of murderer here?

In a way. He is the leader of the Islamic community. It is his responsibility to address the death and he hasn’t. And this really plagues his entire caliphate. Really, from beginning to end, it is civil war. We call Ali’s period the first fitna. He’s always at war with somebody and it’s because of this first rupture, this first moment of ‘this man has been killed and I am responsible for addressing it and I cant because those are the very people who put me in power.’ And because he didn’t punish these people, Mu’awiyah does have the right to claim a stake to the caliphate.So this dogs him forever—well for the very few years actually, not forever, the very few years that he is caliph.

And he does eventually negotiate with Mu’awiyah, but his followers are disgusted by him. They’re so disgusted that he would negotiate that they walk out, many of them, and they are called the Kharijites, which basically means ‘the people who walked out.’ And then they fight with Ali. So he never really has a moment to be caliph. And this is part of what’s so painful for Shias, that the person that they wanted so much to be caliph never really has a fair chance to rule the Islamic community.

So you mentioned that there were negotiations between Ali and Mu’awiyah. What was the outcome of those, other than the departure of the Kharijis from the scene?

Well he does successfully negotiate with Mu’awiyah, and they do come at a peace. It’s not long lived because he gets killed by a Khariji very quickly thereafter. He comes to a deal with Mu’awiyah and then after dealing with him, he has to turn his attention to the Khariji and start fighting the people who were just supporting him the year before. And he battles with them in a very, very bloody war. It’s in Nahrawan in 658 and he creates opposition against him in a time when he really cannot afford it. And while praying in a mosque in Kufa, he’s killed by one of the Khariji seceders. And with his death ends the first fitna. So he rules from 656 to 661.

So does the story end there? Is Mu’awiyah now the unparalleled caliph of the Islamic community? Those familiar with history will recognize the name of his clan; Mu’awiyah was from the Umayyad clan and the Umayyad dynasty is recognized as the first Islamic state outside of the peninsula. So is that the end of the story?

He does become caliph after Ali’s death and the real continuation of the story is with Ali’s children, Hasan and Husayn, and they become really central. Hasan actually cuts a deal with Mu’awiyah and he says, ‘I don’t want any piece of this, I am walking out of this battle.’ This is really problematic for Shias because it contests the very notion that the party of Ali was the one that really deserves the right to rule. He concedes that to Mu’awiyah. He’s eventually killed by his wife, who was actually supporting Mu’awiyah in some way. He’s poisoned and there’s a lot of theories about what this was and what happened.

It was eventually Husayn who would be the one to really go up against another very corrupt caliph, and he’s killed. Shias are more focused on this death, this martyrdom essentially, than any other. This is a real focal point of pain for them, that he would be unsuccessful in defeating an unjust ruler. It calls into question many things, but they have many ceremonies that refer to this. The Ta’zieh plays refer to this, Ashura refers to this. So while the story doesn’t end with Ali, it does sort of reach its end with Husayn in many ways, even though there are imams subsequent to him.

So after Husayn’s death, and this was at the battle of Karbala, what happens to his supporters, the Shia?

At the battle of Karbala, the Shias are really decimated. They don’t have a lot of support from the surrounding communities that did actually support Husayn. So a lot of the mourning ceremonies are more about ‘why didn’t we come out and support Hussein when we had the chance?’

The sister of Husayn, the daughter of Fatimah and Ali, Zaynab becomes really important for Shias. Much like Aisha, who narrates a lot of stories, Zaynab ends up narrating a lot of stories for the Shia community. And this also demonstrates the rift. At this point it’s no longer an issue of who’s the next just caliph; the issue becomes the Shia, the party of Ali, the people who believe Ali should have been the very first caliph, his son should have been the next caliph, and it should have gone on like that, and the people who that believe the Islamic community selected certain leaders and they accept Ali as a just leader.

I think a lot of Shias have a misconception that Sunnis don’t appreciate or accept Ali and that’s not true. He’s part of the four rightly guided caliphs. It goes Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali. And the fact that Aisha fought against Ali is problematic for Sunnis. It does complicate her memory, but they do also accept that there was a rift in that small group of close friends. This is in many ways a family drama. A lot of people didn’t like each other, a lot of people believed the Islamic community should go in different directions, and the Shias and Sunnis have been sort of adding on to the story, elaborating the story, and they continue to be really hurt by this initial moment of warfare that has really lasted for centuries in the imaginations of Muslims.

Related Episodes

- Episode 51: Islam’s Enigmatic Origins

- Episode 58: Islam’s First Civil War

- Episode 82: What Writing Can Tell Us About the Arabs before Islam

- Episode 107: The Yazid Inscription

- Episode 30: Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an

- Episode 57: The Succession to Muhammad

- Episode 61: The Fatimids

- Episode 75: The Birmingham Qur’ān