Every veteran of high school American history knows that the rallying cry of the American revolution was “No taxation without representation!” But what did that rallying cry actually mean? What were the greater principles behind it? And, in an empire upon which the sun never set, were the 13 North American colonies the only place that Britain’s colonial subjects were agitating for a larger role back in London? In this second of a two-part episode, guest James M. Vaughn walks us through the long and often painful process that took our founding fathers away from their original goal of from wanting representation and equal standing with the British motherland to the decision to split off from the world’s most powerful empire and go their own way.

Guests

James M. VaughnAssistant Professor in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin

James M. VaughnAssistant Professor in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Henry Alexander WiencekIndependent Scholar

Henry Alexander WiencekIndependent Scholar

It sounds like you’re really suggesting that this wasn’t a situation in which it was America vs. Britain, it was two people within the empire debating how that empire ought to be run. Can you point to any other places within the British Empire in which a similar debate was taking place?

That’s an excellent point, that it really should not be seen as mother country vs. colony, or American vs British, but rather debate taking place throughout the British Empire about what the future of the British Empire is, and that debate involved people and ideas that were not just British, but beyond the boundaries of the British Empire, from across the Atlantic, and, indeed, beyond the Atlantic world. A good example, to answer your question, is that around the same time the colonial resistance movement is beginning in the 1760s, and the revolution breaks out in 1774 and 1775, is also the period of the origins of the British empire in India, principally in northeastern India, in the richest province of the Mughal Empire, Bengal.

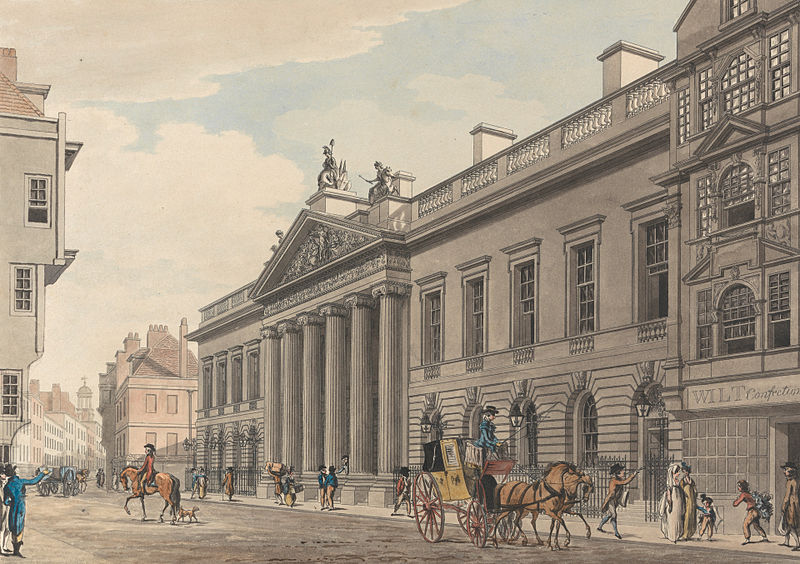

In Bengal, the East India Company has become a sovereign power. It’s transformed from a corporation to a sovereign state, and the British are confronting–British ministers, officials, merchants, how to govern this new empire. There’s actually debates in Calcutta, and debates in the boardrooms of the East India Company on Leidenhall Street in London, and debates in parliament over how this empire should be governed and many people are arguing that this empire needs to be free and open, that there has to be free trade in India, that to some degree British subjects and Asian subjects and indigenous subjects have to be included in processes of governing, that colonists have to be sent out so that Europeans and Asians can mix and create a cosmopolitan society; but ultimately that position loses out. The position that wins out in the boardrooms of the East India Company, and in the committee meetings of Calcutta, and the British political classes is to create a more authoritarian empire, where a small British bureaucratic and military cadre, through a largely indigenous Sepoy army, govern in a despotic fashion these vast territorial acquisitions in northeastern India, and pump out land revenues from those acquisitions.

This kind of development reverberates throughout the empire. There are people in Ireland, there are people in Virginia, there are people in Massachusetts that are deeply disaffected by this kind of authoritarianism brewing in India. A lot of scholars read this wrong, because a lot of scholars point out that, “Oh, look at all these Americans pamphlets making references to Nawabs or Nizams in India, and how they refuse to be like that,” and scholars read this as some kind of [long pause] ethno-centrism, or some kind of racism or Orientalism, which it isn’t at all. What they’re actually suggesting is that the kind of empire that’s being built in British India doesn’t carry the kind of rights or representation or political transparency that the empire has carried elsewhere, and they fear that this might be a new form that will come to them. Invariably colonial radicals interpret increasingly authoritarian and increasingly militaristic and increasingly bureaucratic British imperial measures in North America, like the Quartering Act, like the Stamp Act, like the Intolerable Acts, as part of a new spirit of imperialism that is manifesting itself even more strongly in British India, in Bengal with this despotic authoritarian military state that’s being set up. So you get people in America saying, “We will not be Nawabs,” and they don’t mean anything Orientalist by it. What they mean is, “We will not accept despotic governors that rule above our society instead of in collaboration with and through our society.”

So, it sounds like what you’re suggesting is that the American was not as unique and national as we like to believe and, in fact, was part of a larger and very ordinary debate that was taking place within the Empire as a whole.

That’s absolutely right, and it was a debate that was informed not just by ideas that were brewed in the Empire, but brewed in this wider cauldron of this trans-Atlantic world of the Enlightenment and of the public sphere and of new urban forms of sociability. That’s exactly right.

The first question is: what is the future of the British Empire? And it’s not that the British and the Americans have different answers to that, rather, some conservatives and reactionaries have one set of answers to the future of the British empire, and some radicals have another set of answers to the future of the British empire. And it happens to be that the conservatives and reactionaries win out in the metropolis, they win out in Britain, and they win out in India. But they lose out in North America. But because the conservatives and reactionaries win out in the commanding heights of the British Empire, in London itself, it becomes necessary for the radicals to break from the British Empire.

If I could just stay on this point a bit: the colonial resistance movement does not view itself in isolation. It emerges at exactly the same time as Wilkesite and Parliamentary reformist movements in Britain in the 1760s. There’s a wide sense of the British imperial state both at home and abroad being inadequate to the new commercial and enlightened and manufacturing world of the mid to late 18th century. There are many people, not just the provincial, not just the colonial planters, lawyers, doctors, merchants of north America, but also middling sort and Plebian groups: artisans, shopkeepers, middling merchants in Britain itself demanding reform. The transformation of political institutions so as to make them more responsive to, more representative of this new kind of society. Civil society has developed and changed, and now political institutions have to be more responsible and representative of them.

The cry of “no taxation without representation” is as much a cry of Wilkesites and reformers and members of the society and supporters of the Bill of Rights. SSBR, one of the first major supporters of parliamentary reform that’s founded in 1760s Britain–that’s as much their cry as it is colonial radicals’. So, this was really a pan-British cry, but it’s also a cry that’s taking place in the trans-Atlantic world. It was a cry taking place by radical enlightenment and patriot figures in Rotterdam, in Amsterdam, in Paris, in Lyon, in Naples, in Geneva, all over this world. That’s what’s at stake.

Fundamentally, you can put it this way: the American revolution was about three things. First, it was about the democratization of the British state. It was part of a broader movement across the whole empire and indeed across much of the Atlantic for democratization, and particularly democratization of the British state. And that question, would the british state be democratized–here I mean democracy in the 18th century sense, not necessarily in our sense–would the British state be democratized” opened a second question, which was “What was the future of the British empire?” And behind all of these other things was the profound question of were the political forms of the 18th century Atlantic world adequate for the kind of new society that had come into being in that world?

So, given this new interpretation of the American revolution that you’re proposing, that it’s a real, trans-Atlantic, imperial matter as much as a national one, how would you describe the meaning of the American revolution?

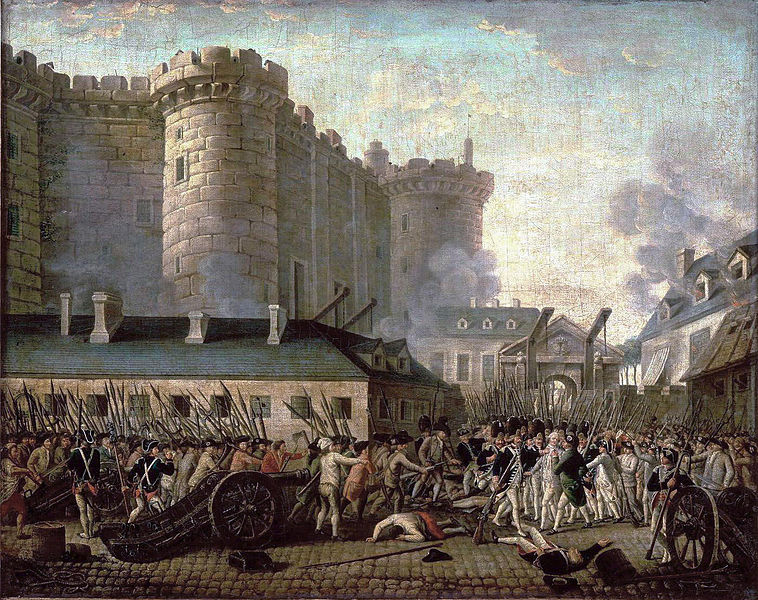

The preface that I’ll say to giving a meaning of the American revolution is that I really think the American revolution should be seen, as you said, as part of this wider trans-Atlantic process. I really think that it should be seen as part of an age of revolution. And, not an revolution that begins in 1789 or even begins in 1776, but rather an age of revolution that begins in the 1750s and 60s, when the old regime, including the absolute monarchies of France, and Austria, and the British parliamentary system begin to experience a lot of crisis and upheaval. These crises and upheavals could be transcended-they had been transcended before-and, in fact, they opened up processes of revolutionary change, and these processes of revolutionary change gave birth to the constitutional republic or the democratic republic.

The essence of that process is that unlike prior political revolts, it wasn’t simply the case that you could make adjustments to the existing political system, as the Glorious Revolution had done, by taking one part of that political system, the traditional parliament and raising it to supremacy over the monarchy and ending the absolute monarchy. That was an incredibly important change that the Glorious Revolution introduced, but the American revolution was part of this wider revolutionary epoch stretching from the 1760s to the 1840s, the fundamental achievement of which was not just to make changes to the pre-existing institutions but to wipe the slate clean and to reconstitute, to literally constitute a new world, to begin the world anew.

And that’s really the most important achievement, of which the American revolution is the first of that revolutionary epoch stretching to the 1840s, which is really the wiping away of all prior institutions. The whole state apparatus of the British Empire, just like the whole state apparatus of old regime France in 1789, begins to be deconstructed and replaced, but it’s not just replaced ad hoc, it’s replaced on the idea of an objectified, written constitution, which provides a framework for a democratic republic of ever expanding participation.

What, I think, people wrongly interpret the constitutional achievement as, they interpret it as a straitjacket, where essentially you’re held in place, like Moses coming down. Washington and Madison and Jay and all these guys, like Moses coming down from Mount Sinai delivering the Ten Commandments and they never can change, no, that’s quite the opposite. These men of the Enlightenment—and women too—believed above all that the world could change. But that the world needed to be subject to self-conscious change, that people rationally and openly debating the fundamental principles of their society and setting up rules for how society changed itself. And so a constitutional republic was about setting down a framework with which everyone in society, even the illiterate, could know there’s no more arcane imperium, there are no secrets of empire, secrets of the crown. Affairs of state are no longer the product of those noble of birth of blood, but are the product of anyone who could read or had read to them the principals of their polity, of their constitution.

Thus, by having those principals read to them, those principles can be subject to a reflective process of ever-expanding debate. Are those principles right? Do those principles grant voting and powers to the appropriate amount of people? Should more people be included? Should they be changed? Really, constitutions were frameworks for societies to have continual debate, critique, discussion about the nature of those societies themselves. And to make them susceptible to change without being destroyed or dissolving. That was the greatest achievement of the American revolution, and really set the stage of this revolutionary epoch was the constitutional democratic republic that allowed people to, for the first time, understand the fundamental principles of their government so as to be able to subject those principles to an ongoing never-ending discussion and debate.