In the age of coronavirus and COVID-19, comparisons are being made to an unusually long-lived and virulent epidemic of influenza that occurred a century ago. The so-called “Spanish” flu went around the world in three waves, claiming more than fifty million lives–more than perished in the just-ended First World War. What was the Spanish flu? Why was it called that? And can we learn anything about what’s in store during the coronavirus pandemic of 2019-20 by casting our eyes back a century?

Guests

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Hi, everyone. Welcome to 15 Minute History. I am here with my good friend, Dr. Christopher Rose, who is here to talk to us about the 1918 Spanish flu.

First off, I hope everybody everyone is keeping safe and social distancing and staying at home. And we’re so glad that you’ve tuned in to our podcast to learn a little bit more about the Spanish flu, which is making its rounds on social media and in the news as a comparison point for the current COVID-19 outbreak. But there’s a lot of misinformation and so we thought it would be a good idea to bring on one of our former co hosts to give us a little bit of information about the Spanish flu. Chris, thanks for being here.

Thanks for inviting me.

Just to inform our listeners if they aren’t familiar with your bio, our newly minted Dr. Christopher rose is a historian of the modern Middle East, specifically focusing on Egypt. He got his PhD in 2018 from the University of Texas at Austin in History, I was there at the defense, it was very exciting. He has authored an article titled “Implications of the Spanish Influenza Pandemic (1918- 1920) for the History of Early 20th century Egypt“, which is forthcoming in the Journal of World History.

So let’s start off with just as a baseline, what was the Spanish flu?

The so called Spanish flu pandemic was a epidemic event that took place between 1918 and 1920. It went around the world in three waves, it was eventually identified as a mutated strain of the H1N1 virus. This is the same one that caused the the so called swine flu pandemic about 10 years ago in 2009. And it was usually virulent and had a very high mortality rate. A mortality rate means the number of cases that ended in fatality. And it also had an unusual morbidity curve is what they call it, which is where, in addition to the usual suspects who are at the highest risk from from death from influenza, which is the very young and the very old people with very strong immune systems, those between the ages of 15 and 25, globally, were also at very high risk of dying from the pandemic because it triggered the body into and an over response, so the immune system would cause the the lungs to fill with fluid in an attempt to kill the virus. And ultimately what would happen is that victims would drown basically from an overstimulated immune system. And the pandemic came right at the end of World War One, as the the treaties were being signed, and troops were on their way home. And so this is believed to have contributed to the spread of the pandemic globally.

One of the questions that I’ve definitely seen on social media is what we should call the virus, because we’ve seen a lot of comparisons between should we be calling COVID-19, the Chinese coronavirus or the should we use the technical term, but I’ve also seen comparisons with the Spanish Flu saying that that was a xenophobic term similar to using Chinese flu now. So why was it called the Spanish flu? And could you talk a little bit about the origins of that term?

So the irony here is that the the name Spanish flu is actually a false analogy with the idea of referring to the corona virus as Chinese because we know for a fact that the the pandemic didn’t originate in Spain. There are three theories as to where the virus actually originated. One is that it originated in France at a British military base. One is that it was imported from China, with Chinese laborers who are being deployed to the Western Front to assist with the French war effort. And one is that it originated in Kansas, and it was actually first detected at a US army base in Kansas that’s now Fort Riley. Apparently, this is well known in that local community. But it was the it was the army medics on the base who first were the first chronologically as far as we can tell with the records that we have to realize that this was an unusually virulent strain of the flu.

But the term Spanish Flu came about because Spain was a neutral country during World War One. And as such, its press was not subjected to military censorship. And so it was the first to sort of freely report on the unusual nature of the outbreak, and when other nations picked it up and their presses were under military censorship, they would sort of refer to the quote unquote virus as seen in Spain as a way of talking about the disease in code. So that people who were reading articles would were supposed to be able to read between the lines and understood that what was being described in Spain was, was actually happening in their own countries, and was what they were seeing in person. And so eventually, the the disease became known as the Spanish flu.

Another term that that was thrown about, interestingly was it was also called the Spanish lady. I guess that made sense in the early part of the 20th century. It seems a bit odd to me now. But in fact, over time, the reason that that was the name has sort of been lost, and people frequently now assumed that that was called Spanish flu because it came from Spain. In fact, I was having a conversation on Twitter last week. And it turns out that a number of people who are Spanish have, at some point been told, you know, your country killed 50 million people in the 1910s. So that memory is still very, very strong. And the idea that that the name was was unfairly given to the Spanish is still very present.

I was actually going to ask, bringing up the historical memory of the Spanish flu and that Spanish being blamed for this. We’re seeing a lot of instances with COVID-19 of racism against Asians. Were there similar racist actions and restrictions against the Spanish during this time where there were travel or people were putting quarantine Was that something that took place during the Spanish flu?

Only to an extent. I think one of the things we have to remember is that one of the reasons that the Spanish stayed out of the war was that they had fought a war with the United States a little over a decade earlier, and lost a number of their global possessions. You know, Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines, Guam, so the Spanish were already kind of our Boogeyman here in the West. So, you know, I think there are probably parallels to be to be made.

One of the things that also came out of the Twitter conversation was people were pointing out that we’re more concerned with with clearing Spain because it’s white, whereas diseases like Zika, or Ebola, which are named for places in Africa don’t get the same treatment.

I think there is a question about the degree to which the Spaniards were considered “white” in the early 20th century, quite frankly, this is the era when, after all, the US was restricting immigration from Southern Europe, because they were too different, that they didn’t want Spanish and Portuguese and Italians and Greeks migrating to the country. So they might not necessarily have been considered of color, but they weren’t considered equals to, you know, Britons and French and Germans and, and, and Scandinavians and the like. So there’s definitely a racial component behind all of this.

You know, viruses have neither ethnicity nor passport nor belief. So viruses aren’t having no nationality. We can talk about whether governments were able to effectively control them, but we have not seen a lot of effective control of viruses pretty much at any point in history.

Yeah, and I want to come back to that point in a second. But first, can you talk a little bit more about what context the Spanish Flu took place in considering the First World War? And you know, you already mentioned Spain being neutral and the important role that that played, but what else is important to know about the role that played in the pandemic.

So there’s a demographer of the war named Jay Winter, who is very adamant that the war didn’t play any role at all in the pandemic. And I would agree with that only insofar as I don’t think World War One caused the Spanish influenza pandemic. Viruses come as they will. And this is probably just a seasonal flu that you know, mutated somewhere, somehow. And there have been conspiracy theories that it was some sort of bio experiment gone bad. But you know, I, again, we’ve seen this virus emerge at other points. But one of the things that it did come into was a world where medical resources were already strained to their maximum, where food resources had been stretched beyond what they could reasonably carry. And so basically, it came into a world where people were already immunocompromised.

Because of the draw down from the war, there was a lot of movement troop bases like the one in Kansas where the virus was first detected. Those guys came from all over the country, they were being stationed there waiting deployment orders. And so, you know, you just had a bunch of people in close quarters, who were a terrific pool of victims who were susceptible to the virus who might otherwise have been exposed. Right now, we’re all about social distancing, right, you know, everyone has to stay at home. And that wasn’t possible because it was wartime.

Right.

So, so that played a huge role. One of the things that that I have argued, and I’m picking up on on work done by other people, is that the food requisitions particularly in colonial settings, I looked at Egypt and I would argue that this is also the case in India as well, where food was being taken by the British colonial government, the French colonial government or what have you, for military purposes, left the local populations malnourished and put them at higher risk for for the disease.

And we see this reflected–because I don’t think I’ve actually mentioned it in this in this episode so far–in the global death toll, which is believed to have been in excess of 50 million, that’s five zero million people. 675,000 in the United States, that is 6.5% mortality. So basically, of the people who caught the disease that’s 6.5 per thousand, you know, that’s extremely high for for a disease like this. And so the war is looming in the background, and and it was definitely a contributing factor. There are large parts of the world that we don’t even have that much data for.

For a long time, it was stated that it’s possible that the virus came from China because there doesn’t appear to have been a very high incidence rate in China. And the fact is we just don’t actually have data for China. So we’re not sure that there wasn’t high incidence, or if we just don’t know, war time destroyed records, records aren’t being kept properly. And this is one of the reasons why the numbers have been in flux, about the death toll and and the infection rates, right.

So in the context of, we have sort of more limited or fluid data about the mortality rate and strategies that different nations were using, what steps were countries taking to try and curb this pandemic? How prepared were they? What happened once it hit? You know, we’re hearing about lots of different approaches now used by different countries. Some are seeing social distancing. Some are, you know, in Italy, there’s full lockdown. So what were some of the strategies that were used were countries prepared when this happened, and then once it did hit, what was it looking like for everyday people dealing with the pandemic?

It’s really interesting from a historical perspective how how little has actually changed in terms of our ability to deal with such a thing. As I mentioned, the the pandemic spread in three waves. The first one was not terribly lethal, it was virulent, by which I mean people got it and one of the reasons why it caught the attention of the medics was that it presented in March. And usually that’s toward the end of the annual flu season. And not only was it in March, but a lot of people seem to be getting it. The really lethal wave was the second wave which popped up toward the end of summer, August, September, that timeframe. Most areas appear to have been hit very hard start between the October and December timeframe. So for example, in Egypt, which is the case study I’ve been looking at, the estimate is that 140,000 Egyptians died in the last eight weeks of 1918, which at the time was over 1% of the population.

The medical infrastructure was overwhelmed. And one of the reasons for that, well, there are a couple of reasons, one of which is that in countries that were at war, a lot of medical professionals had been pressed into into military service. So they weren’t available to serve the civilian population. So those people were just sort of left to carry on as on their own.

The other thing is that this is a time when hospitals were places you went if you had sustained injury and needed constant treatment, but most people were treated at home, the doctors made house calls, right? The idea of when you became sick enough because “it’s just the flu,” to call a doctor and to seek medical treatments. You know, what was also something that played in here. In a number of places there were actually cultural aversions to going to hospitals because, you could recover best at home in the care of your own family.

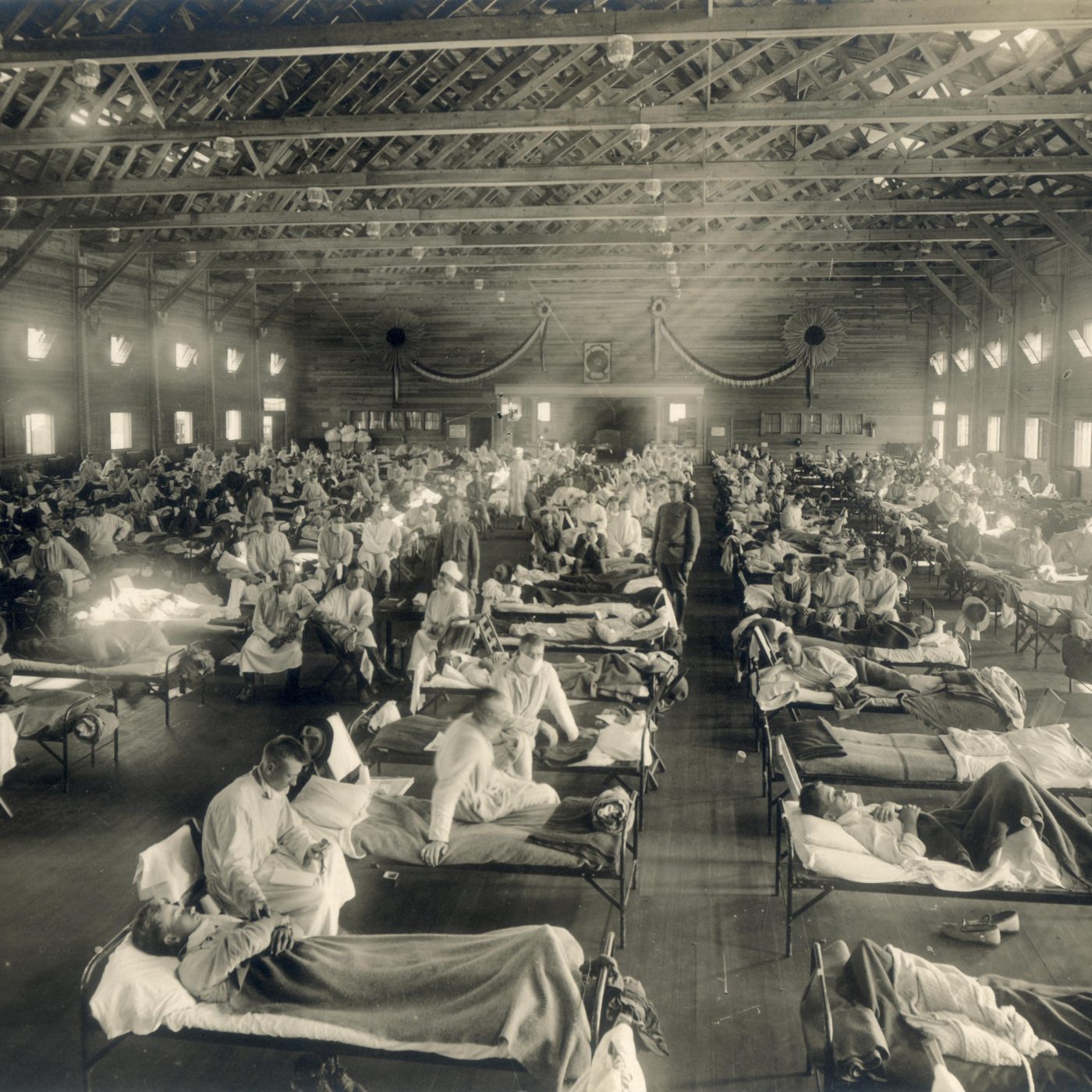

And this is before we even get into to issues of things like racial dynamics, you know. So for example, in the United States, a lot of white doctors would not treat patients of color and that sort of thing. So what you really had in 1918 as we see today was the medical infrastructure just being completely overwhelmed you know, that we’ve I think we’ve all seen now photos and social media of you know, the the sort of field hospitals set up in gymnasiums and, and other structures to treat victims of the influenza, just like we have with Corona virus, but the other, you know, simple factors that this is prior to the age of antibiotics, you know, there really was no effective treatment for influence at the time. So you just kind of had to rideit out and hope that the the disease would eventually wear down on its own.

But in terms of government response, shutdowns, yeah, schools started to shut down factories were shut down, and sometimes it wasn’t even done necessarily, by government order. People just didn’t show up to work because too many people were sick, there were places where agricultural production ceased. And so, you know, it’s almost harder to tell whether or not you know, people died of the the influenza per se or whether it was coupled with malnutrition because, again, food delivery and supply was shut off. And really there’s a reason why people still remember this as a time of massive suffering, because, you know, the the response was, was was inadequate on on a global level.

And what were the economic impacts of the pandemic?

So it this is an interesting question. And honestly, there haven’t been a lot of global studies about the economic impact. So there was a study that came out in 2003 by Elizabeth Brainard and Mark Siegler, looking at the impact in the United States. And basically, their argument was, again, this will ring familiar to a lot of our listeners–that the the sort of global shock of the epidemic had its biggest impact on small businesses, which were the most likely to fail. And that a lot of this sort of economic growth that we saw in the 1920s was really returned to normality, especially in the early part of the decade. They don’t go as far as drawing a connection between the economic shock from the influenza and the Great Depression, because their argument was that we had exceeded you know, we’d return to normality and then exceeded it by then. But that there was a bit of a slump in and economic production. So that’s one of those areas that we’re just starting to look at much of the new scholarship on the pandemic and it’s both both its medical and social, and economic effect is real. I had a list in front of me and most of the articles have been written since the year 2000. So, you know, this is all all pretty new scholarship.

But that’s fascinating and to end I wanted to ask you, even though you’re a doctor, you’re not the doctor that actively is saving people right now, but I wanted to ask you what lessons you think we can draw from the Spanish influenza to the current pandemic.

I think there’s a number of lessons that we can draw, one of which is that especially in the last few days, you know, we’ve had these these debates about whether or not we’re doing more harm than good by by ordering people to go home is that the Spanish influenza pandemic really was a period when we saw what happened when the medical infrastructure gets overwhelmed and that the rationale for what we’re currently calling social distancing isn’t just about making sure that people don’t get sick, but it’s also about making sure that the hospitals are able to treat patients who need treatments.

So, for example, you and I are in Austin, Texas, where we have just under 100 confirmed cases of COVID-19. And the statistics that were released on Tuesday, that Tuesday, March 24, said that of those half of those cases in people under 40 years of age. Number one, this this sort of belies the the prevailing narrative that this is a disease that only affects the elderly. And it may be true that the elderly are more at risk of dying. But again, for every one of those 40 people who may need a medical boost in order to get through their case, you know, that could also be a hospital bed that would be denied somebody who is at much higher risk of dying. And you you, we don’t want to have obviously make judgment calls about who shouldn’t shouldn’t be treated, or at least that’s what we’re trying to avoid here.

Right.

Again, if we look back in history, we’ve seen that this has happened before. And I think this is one of the things that we’re trying to avoid encouraging people to stay home and encouraging people to just try to be healthy and practice good hygiene. And I won’t lie. I have wondered what people were doing before the the current crisis since we apparently nobody knew how to wash their hands

I was thinking about how many people have suddenly started washing their hands?

Right? What were you doing beforehand? (laughs) But, but you know, part of it is this, this is where it comes from is, you know, we’ve been through this before. We are now as as they were in 19 1918, quarantines were relatively useless because once the virus is in a place and started to spread, you can’t do much about it. What you can do is try to slow it down to spread internally in order to give the infrastructure a chance to work in order to give the government chance to put a response into place. And that’s what we’re doing now. And I think it’s important that we not lose sight of, of that being the ultimate goal, which is this is about making sure that more people don’t get sick and that we can slow it down. It’s not necessarily about, you know, trying to stop the epidemic altogether, although this is certainly one of the ways that it can be done.