Between 1910 and 1920, an era of state-sanctioned racial violence descended upon the U.S.-Mexico border. Texas Rangers, local ranchers, and U.S. soldiers terrorized ethnic Mexican communities, under the guise of community policing. They enjoyed a culture of impunity, in which, despite state investigations, no one was ever prosecuted. This period left generations of Texans with a deep sense of injustice, and representations of this period in popular culture still celebrate police violence against ethnic Mexicans. Yet families fought back, demanding justice for atrocities against Mexican-American communities.

Guest Monica Martínez of Brown University joins us today to discuss what happened on the Texas border a hundred years ago. She also reveals the striking similarities of the period to the Trump administration’s November 2018 decision to send military troops to the border.

Guests

Monica MartínezAssistant Professor of American Studies at Brown University

Monica MartínezAssistant Professor of American Studies at Brown University

Hosts

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Hi, everyone. My name is Augusta Dell’Omo, and I’m here with Professor Monica Martínez, who is an assistant professor of American Studies at Brown University, focusing on Latinx studies, immigration, histories of violence, policing, and public memory in US history. She’s also a public historian and activist, as a primary investigator for “Mapping Violence,” a digital project that documents histories of racial violence in Texas, and she is a founding member of the nonprofit organization “Refusing to Forget” that calls for a public reckoning with racial violence in Texas. Professor Martinez is here today to discuss the historical context of the Trump administration’s decision to send military troops the border, which is strikingly similar to what took place 100 years ago. Professor Martinez, thank you for being here.

Thank you for having me.

So why don’t we start with what happened a hundred years ago on the Texas border?

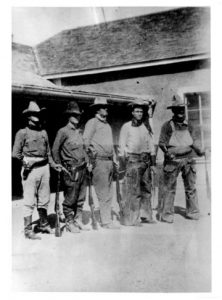

Well, a hundred years ago, that was really an era of violent policing that took place in Texas, I study more specifically the decade between 1910 and 1920 and it was a period of state sanctioned racial violence and terror. So, one of the events that is a good example of this, is the Porvenir Massacre in January 28, 1918, a group of Texas Rangers, local ranchers, and US soldiers descended on the community of Porvenir in the middle of the night and woke the residents from their homes and separated you know, the men and boys, fifteen men and boys, from the rest of the families, and they massacred them. And so, you know, these victims were in police custody, and they died, you know, at this brutal, brutal death.

But this massacre brought to light, it shone a light, on the kinds of abuse that was taking place, where ethnic Mexicans were being murdered without due process. And the Texas Rangers, US soldiers, or local vigilantes that participated in these kinds of crimes were not being prosecuted. And so they enjoyed a culture of impunity. And so, this massacre is one of the cases that is seen as the most egregious, but it really give us an example of the kinds of murders that were taking place throughout the decade. So, the Porvenir Massacre resulted in state investigations, investigations by the Mexican government, by the US government. And despite the final findings of the atrocity itself, nobody was prosecuted. And so it also gives us a sense of this period of racial violence that left generations of Texans with the sense of with a deep sense of the injustice, not just of the violent itself, but the injustice of there never being prosecutions, people never being held accountable. And even in the way that the history has been told, you see historians and popular culture, you know, celebrating violence at the hands of police, of Texas Rangers, in particular, when they are policing racial and ethnic groups. And so that lasting sense of injustice has lingered throughout the 20th century.

And so it sounds like there’s an intersection of local and state violence that’s happening in this period. Is that similar? In what ways is it different from the kind of national dialogue that we see now, and sort of the Trump administration and differences between how state power is executed in the same or different ways?

Well, it’s, it’s complicated. So in the early 20th century, there had been a long history of using the US military as a mechanism for nation-building. And so, you know, of course, some people are familiar with, with Texas history and Texas independence, most Americans don’t know about the US-Mexico War. So this war between 1846 and 1848, which resulted in the United States acquiring half of Mexico’s territory, and, you know, the residents that were in the states and, you know, what is now California and Arizona and Texas could decide whether or not to become American citizens. But with the acquisition of that territory, and those residents becoming American citizens in 1848, that doesn’t mean that the ways in which we understand the US-Mexico border existing today, you know, happened overnight: wasn’t really until not even until the late 19th century, I mean, the 1880s and 1890s, when the US-Mexico border was actually mapped by survey teams and military teams. And so the development of this border region through war, and conquest, and colonization is something that is a longer deeper history.

But what we’re seeing today are the ways in which, you know, the current administration, but also Texas officials, call for a militarization of the border. They described the border as a place the border between, for example, Texas and Mexico, as this place of danger. And so what you see are politicians that use the border and the need to police the border and border residents as political rhetoric that gains currency, stokes fear, and so there was a lot of fear that was used to justify, between 1914 and 1917, you know, there was 100,000 US troops that were sent to police the border between Arizona and Brownsville, Texas. And so we’re seeing, again, the ways in which the border is being used as a place to stage national power. And in state building, it’s a way of nation building by, again, performing this control of the ability to be able to police the border.

Right. And from your research. Do you have any sense of what kind of triggers these patterns have increased militarization, violence, you spoke a little bit about revolution and Mexico or is it driven just as much by sort of internal demands, like you said, for, for nationhood and state building and self-identity and formation?

Well, in the early 20th century, it was also deeply connected to what has been described as the farm colonization of South Texas. And so you have the arrival of the railroad to Brownsville in 1904, you know, for, for example, which opens up South Texas for an agricultural economy. And so it becomes possible for farmers to start to change the way that the landscape is used in South Texas. And so previously, you know, the economy was a ranching economy, farms that existed were large, you know, about 1000 acres of farm land. But with the arrival of the railroad, you started to see land companies and development companies recruiting Anglo farmers from other parts of the country. And so you what you saw was a shifting racial hierarchy. And so there was an effort to displace Mexican landowners in South Texas. And this is something that had taken place over decades, but in the early 20th century that is expedited. And so you start to see, you know, lands being transformed from ranch use to farm land. And so the farmers are much smaller, but what these farmers bring with them, what Anglo farmers bring with them from the south and from other northern states, are new understandings of racial hierarchies.

And so in addition to changing the way that land is use, they also introduced Jim Crow segregation style laws. And so you start to see laws that segregate Mexican children, you know, even those who are American citizens, from white children, you start to see laws that discriminate and disenfranchise Mexicans who were voting at the time and, and also that change in this farming agriculture really supplants and replaces the Mexican landowning class and Mexicans are relegated to wage labor that so then they’re working for, for wage labor on these farms. So that shift in this period of colonization of south Texas is coupled with this call to interrupt the ways in which people who lived in that period, moved fluidly across the border. And so you had people who worked in Brownsville, but owned a home in Matamoros, just south of the border. And so part of the calls by these new-Anglo farmers to change the racial hierarchy, right to make Anglo, these new Anglo rivals, the economic and cultural elite, was also that they wanted to change the movement across the border. And so it became a way of actually, of nation building, but also bringing white supremacist ideals to South Texas. And so those inform the kinds of calls also for policing in border militarization.

Right. And it’s that kind of fluidity as threatening to the kind of hierarchy that you’re talking about, right? And so when you’re working in this period, how do you center the victims of this state violence and reconcile their experiences with official narratives and collective memory for most Americans that hides a lot of these atrocities?

Well, you know, part of it is to, to tap into the long tradition of generational memory. And so for this period of violence, when you had state-sanctioned violence in between 1910 and 1920, it’s estimated that that hundreds of ethnic Mexicans were murdered, that, you know, when you return to state archives, very few of these murders have been recorded. And so there isn’t a complete index of the people that died during this era. And so there’s the, the popular corrido tradition, the Mexican ballad tradition, that describes some of the violence and some of the conflict from this era. But I’ve made use of oral histories that give me access to the tradition of generations of Texans, passing down stories from one generation to the next, of the kinds of murders that impacted their families or their neighbors. In some cases, it’s people who witnessed a murder and were impacted by that. And these, this oral tradition wasn’t just preserved within Mexican-American communities. There were Anglo-Texans who witnessed atrocities and preserved the memory and did so as a way of refusing for these injustices, refusing for the injustices to be forgotten. And so in terms of centering the humanity, I talked about, in my book, that the recovery effort is a search for lost humanity. And so, you know, documenting the names of people that were murdered, the circumstances, the people who brought them harm, the circumstances of their death, but also trying to give readers access to what their lives were, like who they were the, for the example of the Porvenir Massacre, if you look at the newspaper accounts, and some of the police reports in the aftermath of the massacre, you know, the men and were described as men, there were actually two boys were a part of the victims and number of victims and, but newspaper accounts, described them as squatters, as bandits. And so part of the archival work that I’ve done to come back to that community is to actually show how many of them owned land, how many of them were farmers, the kinds of produce that they grew, and the school – there was a school run by a local teacher – and he kept the names of the students that attended the school so I can list the families that sent their children to school. And so giving those details of the community give us access to the people that we lost, but also to the community that was disrupted.

The other important part of this recovery work is also describing and documenting how these murders, these massacres, in this case, impacted the survivors, the people who were there that night, the widows, the children, the neighbors, and showing the impact on those families in the days and the weeks in the month after, but also the impact across generations. So for the Porvenir massacre, there were twelve relatives that filed a suit against the United States government, you know, and this took, you know, the very next day after the massacre, they were giving sworn statements to describe the brutality that they experienced. And, you know, giving the names of the dead asking for the right to return to, to bury the remains. And so, but they also then went on to, to try to seek an indemnity from the United States government for the not only the role of law enforcement in the murder, but the denial of justice, because nobody was ever prosecuted. And so returning to these histories, you know, I look for that humanity by trying to just move away from, you know, the date and the name and the place, but actually asking “who was this person and who was impacted by their murder?”

Right, in your reconstructing their entire life is more than just this one moment of violence, but what they meant to the larger community that they were a part of, and as you were studying kind of how these communities responded to the violence they experience, were there strategies that seemed to kind of permeate across local differences, was petitioning to the government something that was typical or atypical? Or was this oral intergenerational tradition, kind of the primary mechanism? What sort of things did you see during your investigation?

Yeah, well, so I found more through this, the claim that was filed by the survivors of the Porvenir Massacre that introduced me to other claims that were filed through the US-Mexico General Claims Commission. And so in the case where some people that were murdered were Mexican nationals, it was, it was common for Mexican consulates to be involved in different ways. And so in some cases, they asked simply for investigations. And so they would take testimonies from witnesses, from surviving family members, and call on the state of Texas to investigate the murder. So I open the book with a case of a father, Miguel Garcia, who’s looking for his son, Fulgencio, who’s disappeared, and when, you know, Miguel is traveling to, you know, the county attorney to ask for an investigation for help in finding his son. And so the Mexican consulate, you know, after the Mexican Consolers are involved, after the remains of his body of his son found. And so that leads to an investigation and the Texas Rangers that witnesses saw with Fulgencio Garcia, having him in their custody, were arrested, a local grand jury decided not to indict the men. So you see families seeking justice was something that I had not anticipated when I initially started the research, but and I found more through the US-Mexico General Claims Commission of widows, of parents, filing cases against the United States government. So there’s a legal archive that has been overlooked by most historians of this period.

I was also really captivated by the numbers of law enforcement officers who protested, and so they wrote letters to the Governor, like Sheriff Vonn of Brownsville, you know, describing some of the injustices describing Mexicans that were being killed without due process, and asking for a Texas Rangers to be removed from Cameron County. There was also an attorney Frank Pierce, who started writing down the names of people that he knew had been murdered without due process. And he, you know, sent telegrams to state officials. So in addition to the families that were seeking justice for the violence, there were also bystanders. So we’re, you know, we today, we would call them whistleblowers, you know, members of law enforcement that tried to bring an end to the violence. And, you know, for the most part, I think historians have paid attention to the role of violence at the hands of Texas Rangers. But I also found cases of, of, you know, Concepcion Garcia was a young girl who was living in Texas for school, her family lived in Mexico, and she became ill in April 1919. So her mother and aunt came to Texas, and they picked her up, and took her home to care for her. And as the family was crossing the river, they were shot at by a US soldier. And so I found a number of people that were shot while crossing the border by US soldiers that later filed indemnities against the United States. And so it’s a, it’s striking to see some of the death take place in in places along the border today, where you see again, you know, either Border Patrol agents or US soldiers, you know, where people are dying the border.

And so when you’re kind of looking at the sort of activism that took place were there additional ways that people were, particularly cross gender lines, were men and women kind of dealing with this sort of violence in different ways?

Yeah, well, there, you know, one of the people that that really resonates with Jovita Idár, and she was a journalist, and a teacher, who was a part of the Idár family from Laredo, Texas. Her family had a newspaper called La Crónica, and she is really captivating, not only because of the work that she did as a journalist, in documenting anti-Mexican violence. So she wrote about lynchings that took place at a time, mob violence that targeted Mexican men, but she also helped with her family to organize, El Primer Congreso Mexicanista, which was a civil rights conference in Laredo that took place in 1911. But the people that attended came from south Texas, but also from northern Mexico. And so it was this really inspiring conference where you see that people in the midst of people calling for the border to be a dividing line, people like Jovita Idár were cross border organizing for civil rights. And so they were discussing anti Mexican violence, certainly, but they were also discussing access to schools for Mexican children, labor exploitation, and she was talking about women’s suffrage. And so she was talking about the right for women, to vote for women to be educated, and to have, you know, jobs and get access to schooling. And so you know, this if we think about this period, only as a period of racial violence then we missed the opportunity to tap into these the history of the efforts for social justice. And so there were a lot of people calling for social justice and for social change in this era. And unfortunately, when we forget this history, we forget people like Jovita Idár.

Right. And you mentioned a little bit earlier talking about the historical markers for some of these events. Can you talk a little bit about your work with that, and how you think that contributes to, not just in Texas, but sort of as a collective Americans, we understand and should understand this history of border violence?

Well, so I started working with my colleagues and “Refusing to Forget,” in 2013. We’re a group of historians primarily, but you know, John Morán González, who’s here at UT Austin, he’s in the English department, and so we came together to try to, in recognizing that 2015 was going to be the 100-year anniversary of the peak of anti-Mexican violence. And so we wanted to find strategies for how to commemorate, and what we really observed was that despite decades of scholars, you know, not just historians, but also people in English and Literary Studies writing about this period of violence, there had been little shift in public understanding of this period. And so we wanted to participate in public history, and engage with cultural institutions in Texas to try to bring about public understanding of this era of violence. And, originally we thought, well, we can have museum exhibit, it can be at UT-Austin at central we know, will raise some funds for one monument or a marker of some sort to have, you know, in south Texas, but with my work with descendants, who have been on their own, preserving these histories, preserving private archives, researching the histories of violence, I also met people like Norma Longoria Rodriguez, who has been writing about her family history, the double murder of Jesus Bazán and Antonio Longoria in September 1915, she’s written poetry, she’s written, you know, she recorded interviews with her family members. And so she created an archive of the double murder, but she’s also been doing things like publishing her poetry and publishing online, you know, memorials. And so for her, and for other descendants, it was really important for a hundred years after these events for the state to finally participate in acknowledging this period of state sanctioned violence. And so that really shifted the thinking for “Refusing to Forget” that we needed to engage Texas cultural institutions like the Bullock Texas State History Museum, and the Texas Historical Commission.

And we’ve been a tremendously we found, you know, great collaborators in the Bullock Museum and the staff, you know, “Life and Death on the Border,” the exhibit that we unveiled was a temporary exhibit, that was unveiled in January 2016, it was only up for ten weeks, but, you know, estimated that 40,000 people came to see that exhibit, and teachers came to see the exhibit and students came and so, you know, that is a reminder of how many people want access to these kinds of history, a truthful accounting of the past, but the Texas State historical markers also play an important role. Because what that it’s the manifestation of calls for by generations for the state to acknowledge some of these crimes. So the marker that we unveiled in October 2017, in Cameron County for La Matanza describes this period of violence, the peak of violence in 1915, and it describes, you know, and the state sanctioned violence, but it also recognizes the people whose names we may never recover. So it speaks to the gravity of the period itself. The marker that we just unveiled in Hidalgo County for, you know, Jesús Bazán and Antonio Longoria that’s for one specific event. But again, it speaks to the broader context of the period, and also highlights the importance of attending to and recognizing the loss of life. And so in this case, it’s a double murder of two men. But it also highlights you know, that that nobody was prosecuted for the crime. And so it speak to the broader injustice of these kinds of acts of violence.

Yeah, and also, you know, there’s been a lot of work at UT with sort of trying to pull through, like you said, some of these layers of getting to a more truthful telling of history. There’s professors at the UT history department, such as Emilio Zamora, that’s been working with the Texas, sort of controversy over textbooks and things like that. So what are some of the things that you’ve seen with resistance to the kind of truthful telling that you’re trying to put into place through public history markers, things like that?

Well, I’ll say, you know, I wanted to acknowledge, just as you did the important work that’s been done here at UT, you know, it’s going to be, it’s just tremendous that in 2019 students are going to have at be able to take in Texas, Mexican American Studies in in public schools, and they can have access to that, you know, for school credit. That’s tremendous. And, and it’s thanks to the hard work of historians across the state of Texas, and teachers across the state of Texas. But, you know, faculty here on campus have played a particularly important role. So I just, you know, that’s a moment to celebrate.

In terms of some of the resistance, you know, I mean, there’s, I mean, you could think about, you know, the efforts to silence this history. And that has taken place over the course of a century. So, you know, historians like Walter Prescott-Webb, in 1935 published his account of the Texas Rangers, you know, and he spoke, he described this era as an “orgy of bloodshed,” but he also consistently justified the violence, you know, he spoke about Mexicans, as, you know, a mongrel race, as you know, in many of the cases that I write about, you know, if, if they appear in his book, he justified the violence and he was echoing the, the, the role of the state and, you know, even the Texas Ranger investigating officers, that when cases of abuse came to the state administration, they pretty consistently justified the violence, you know, they justified saying, this Mexican was violent, we’re better off without him. You know, that’s an oversimplification, but you saw consistent effort to justify the violence. So there has been a long history of trying to,

on the one hand, trying to erase the history by not creating records, on the other hand, creating this narrative, you know, that Mexicans are violent, and they have to be policed brutally, and that the people who do that violent policing are heroes. And so, you see, see, you know, Texas Rangers are, are celebrated in popular culture and history in public exhibition.

But so you could say that there’s been a long sustained effort by historians, by cultural institutions by the media to keep this history, these accounts of injustice, from being made public. More recently, you know, we’ve had good luck in working with some counties in collaboration with the Texas Historical Commission, and local county historical commissions in Cameron County, and Hidalgo County, and in Webb County where we’ve found that the historical commissions are glad that there is some leadership from the state to create an opportunity for them to grapple with these histories. But we have also come up against, or we’ve also now been finding, just within the last few months, really since August, that there are some residents who are willing to mobilize whatever sort of political power they have, to stop some of these commemorations and so we were supposed to have a historical marker unveiling for Porvenir Massacre on September 1, and, you know, the marker was the order was at the foundry, the market was going to be cast, and you know, I’ve received some emails and some phone calls letting me know that I had been halted. And so we’re still trying to move that forward. But what it brings to the forefront is that, you know, even a hundred years later, it’s unfortunately difficult for some Texans to acknowledge, you know, cold blooded murder, you know, the denial of due process, to call that out as wrong, and has an injustice and that a hundred years later, we should be able to say, we don’t want to repeat that kind of policing again.

For people trying to understand this period and understand what’s happening now, what are some of the both you know, you’ve talked a lot about the similarities, but are there differences in what happened a hundred years ago and what we’re seeing now that you would want sort of contemporary young historians, contemporary young students, to kind of see as these are the differences and what’s happening that and what’s happening now?

The differences…well, I mean I do see a lot of stuff a lot of similarity. So I mean on the one hand there was a 1914, you know there was a refugee prison camp in Fort Bliss you know which is a military base outside of El Paso, and so you know the detention centers that we see across the state of Texas, but also across the country, are…okay I’ll say this: so hundred years ago if anybody was just labeled a bandit, or described as a bandit or described as banditry that was a license to kill. And so, you saw that take place after somebody was killed, you know, in some cases, they would just be accused of being a bandit to, you know, that kinds of violence, you know, just, you know, shooting people on sight, you know, isn’t taking place on a map on a scale like it was between 1910-1920.

On the other hand, you know, in every county that we’re, we’re having a historical marker unveiling, you know, there are detention centers, you know, where people are being denied due process, where people who are seeking asylum are being denied the right to seek asylum. The kinds of militarization of the border today and what some people are calling for, what the administration is called for, to say, we’re going to close the border and deny people a right to seek asylum, you know, that’s breaking with international law and international customs. And so it’s you know, I think in terms of looking at the patterns of similarity, you know, denying people due process, racial profiling, criminalization, you know, impacts the people who are being policed, but also you know, other people who are profiled within the United States. One of the big differences that I see in terms of the immigration policing regime is the number of American citizens that are being impacted across the country. So deportations, for example, of people who are undocumented affect American citizen children. The policing that happens in immigrant and Latinx neighborhoods you know, terrifies not just some people who are being hunted, but the entire communities. And so, you know, I’m really gripped, you know, but, you know, the Border Patrol was, was developed in1924, but I’m still really shocked to see the Border Patrol, you know, in New Hampshire. There are raids and deportation raids that take place in Massachusetts, and across the country. And so I think if, if anything, the technologies for containing people in detention centers and private prisons has spread across the country, and in many ways, the border policing, as historians understand it a hundred years ago, is now taking place across the country. Also with “Refusing to Forget,” I worked with some students at Brown, to write a lesson plan that matches TEKS (Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills) for Texas history and, you know, the work continues to try to make this history public, and for it to be something that can be taught in public schools.

Awesome. Thank you so much Professor Martinez for being here, this has been another great episode of 15 Minute History. Thank you so much for listening.

Thank you