With the death of Nelson Mandela in December 2013, attention turned once again to the conditions that brought him international acclaim as the first black president of South Africa, and overseer of a process of national reconciliation that kept the country from falling into bloodshed. But what was the system of apartheid that he and millions of other South Africans had rallied against for so long? Where did it come from? How was it enforced? And what brought it to an end? Guest Joseph Parrott helps us understand the system of “separateness” that dominated the lives of South Africans of all races for so long, and introduces us to the key organizations and players that fought against it and finally dismantled it.

Guests

R. Joseph ParrottAssistant Professor of History, the Ohio State University

R. Joseph ParrottAssistant Professor of History, the Ohio State University

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

We are going to be talking about apartheid today. So, why don’t we start there, with a definition: what was apartheid? Where was it?

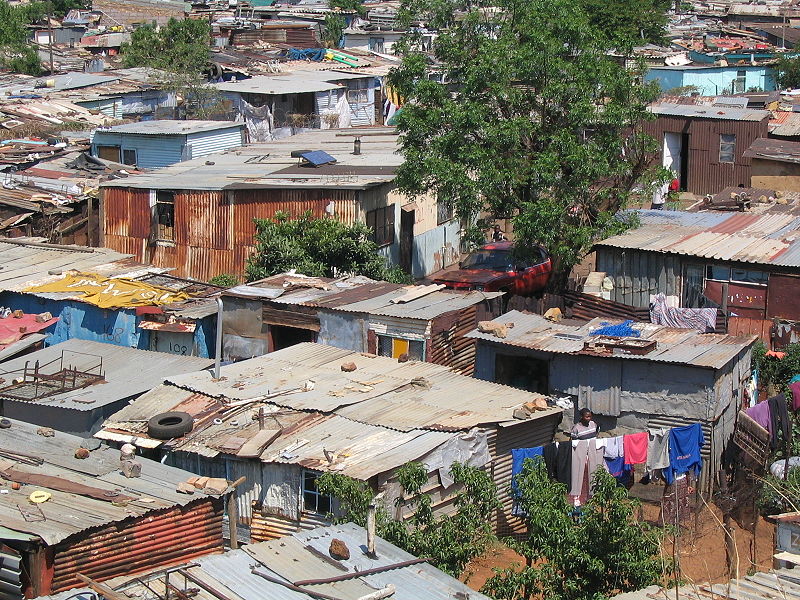

Apartheid was the policy of almost complete segregation of people along racial lines that was practiced in South Africa between 1948 and 1994. It means “separateness” in Afrikaans, which was the language of the white minority government during this period. It placed controls on African peoples, Asian peoples, mixed race peoples in this country. It defined limits on where people could live, what jobs they could take, and even how they could move around the country. It was most rigidly applied to black Africans, and allowed the white minority government to build an excellent standard of living while relegating the rest of the population of the country into undesirable agricultural areas or urban slums. It was a violation of international standards of human rights and it brought international criticism and domestic revolt on the government. These twin pressures led to its collapse in 1994.

What were the origins of the policy? When did it originate?

It went back into the colonial period, after the Dutch first colonized the country with Afrikaaner groups–they were the descendants of the Dutch–and the British empire. It came from a desire for economic expansion. The discovery of gold and diamonds in the late 1800s pushed Europeans to look at native peoples as a source of cheap labor. Ideas of racial and civilizational superiority led the British government, and later the Afrikaaner government, to establish increasingly strict regulations on African travel and work in order to make sure that there was an affordable labor force to work in the mines.

So, that was all before the 1940s. How did the actual laws of apartheid differ from these earlier laws?

The Afrikaaner government in 1948, under the National Party, kind of formalized and standardized these earlier piecemeal segregation practices that differed from region to region and it gathered together these local laws, these different laws, and created one unified national system. The government divided the state into what they called separate racial nations, forcing Africans into reserves and townships. The government banned intermarriage and created a wholly separate and extremely unequal education systems and public spaces.

This policy reached its peak in the 1960s when the national government sought to establish what it called “Bantustans,” which were where Africans would have nominal self-government under a system of tribal leaderships, but in reality these states were occupying the worst lands, and they were wholly dependent politically and economically on the state of South Africa, which completely surrounded them. And so, this represented the final step in creating a wholly separate and wholly unequal way of life between this minority and the African and Indian populations, and in many ways it was an extremely exaggerated version of the racial segregation that was going on here in the United States.

How did the African majority react to apartheid?

Obviously, the vast majority of the non-white population really didn’t agree with these restrictions, and over time they attempted to resist many of them.

The African National Congress was the first group to organize against these laws. It was founded in 1912 as a traditionally moderate party, attempting to change the laws themselves, but by the 1940s the ANC had developed a more dynamic young leadership that was trying to move toward a mass protest, a mass movement. Among this young generation was Nelson Mandela. The ANC hoped to replace apartheid with a more multiracial policy, a more multiracial government. At the same time that the ANC was organizing, there were other groups, the most famous of which is probably the Pan Africanist Congress, and these other groups had other ideas–the PAC wanted a more African centered government–but all together these various parties, they urged strikes, they urged boycotts, and general defiance campaigns demonstrated their unhappiness with these laws.

How did the government react to boycotts and strikes and defiance?

Well, of course these boycotts and things, they struck at the heart of white rule, so the government had to do something, it had to react. So, in the 1950s and 1960s, it expanded its powers to control these nationalist, these African parties, and it attempted to silence the majority of their leaders. So, parties like the ANC continued to defy this official policy, but it found it harder going. The government attempted to end these protests with force, and this culminated in the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960.

This happened in a township just south of Johannesburg, where police killed 69 anti-apartheid protestors. After these mass protests erupted throughout the country, the panicked Afrikaaner authorities banned both the ANC and the PAC, and imprisoned much of the anti-apartheid leadership, including Nelson Mandela who, by this point, had become the head of the violent wing of the ANC. These actions undermined the mass agitation against apartheid, but it couldn’t stop everything. Individual acts of defiance and a general feeling of anger remained underneath the surface of the country.

Did it attract attention internationally, or was South Africa just left to carry out its human rights abuses on its own?

Absolutely. There was a lot of international attention that was growing throughout this period. Most people around the world viewed apartheid as this unpleasant anachronism. You need to remember that apartheid appeared at the beginning of a period where we had decolonization in Africa and Asia, and also in the early years of the civil rights movement here in the United States. The whole world seemed to be moving in one direction and South Africa was going backward, right? Away from racial equality.

That’s not to say that everyone saw it this way. In the US, especially, segregationists in the south and the hard core Cold Warriors in the government thought that South Africa was doing a good job “developing” its African peoples and also keeping communism out of the region, but more generally there was a sense of unease with these policies. Most people felt that the Afrikaaner government was really violating human rights and, so the passage of laws controlling the movement of non-white people, and, especially, Sharpeville, turned the feelings of unease into action. The United Nations was at the forefront criticizing apartheid, but not really accomplishing much. In the United States, there were non-governmental organizations like the American Committee on Africa, sometimes called the ACOA, that helped organized boycotts and urged the American government to further isolate South Africa. A lot of these movements arose throughout the world, similar ones in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, and Japan, and really all across the political spectrum internationally.

And, in the US, in the 1980s, there was an anti-apartheid movement calling for companies to withdraw investment and support for the South African economy? The divestment campaign. Was that important? What was that about, and what role did it play in the international movement criticizing apartheid?

Divestment was big, and it kind of evolved from this earlier organizing. In 1976 there was another South African student protest in the township of Soweto, and it again turned violent. The South Africans came in and forcibly put down the student rebellion–all they wanted was more liberal education. This became international news; people were horrified by these actions as they had been after Sharpeville, and these older movements took advantage of this new interest in South Africa. A number of new groups arose around the kind of traditional core. TransAfrica was one of the most interesting–TransAfrica was an African American group–

Was that in the US?

Yes, that was in the US, and its members started a number of different things. They had a 24 hour picket of the South African embassy. They lobbied Congress, and they raised funds for anti-apartheid groups at concerts, and things like this. And generally these activists latched onto South Africa because they saw it as an issue of racial equality, it related to what they were fighting for at home. But at the same time, there were a number of South Africans in exile who lived in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere and helped guide and inspire these movements. Oliver Tambo, for instance, was a very important figure (the airport in Johannesburg is now named for him). He was the president of the ANC during this period, and he helped cultivate this solidarity internationally. Anglican archbishop Desmond Tutu, who’s probably a familiar name to some folks, became an important voice, and he was especially influential in getting religious groups involved.

As the anti-apartheid movement grew throughout the 1980s, students became really active, and in 1986 it kind of reached this peak where there was a real victory. The American congress, inspired by its constituents, banned trade and investment in South Africa, over the veto of Ronald Reagan, who wanted to continue attracting South Africa through trade. This was the peak of the protest in many ways. Japan and a number of other countries followed suit, and South Africa was really isolated internationally.

Did the international movement bring about the end of apartheid?

No, certainly not. That’s a little bit too simplistic. The international level was important, but the regime really fell because of events that were going on within South Africa itself.

After Soweto, you get a new domestic insurgency that’s coming about because African peoples are just tired of it.

And remind us, when was Soweto?

Soweto was in 1976. So, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the ANC, and the PAC, are both trying to start insurgencies. Part of the reason was because the country faced a deep economic crisis in the late 1970s, as many other countries did, but this crisis was exacerbated by the fact that modernization hadn’t happened in the industrial sectors. Cheap African labor prevented South Africa from having to mechanize or innovate, and so there was this kind of general malaise. And when that hit the country, it trickled down very harshly to the african population. So, with little to lose, they were more willing to take up arms against this minority government that had been repressing them for so long.

So, did the economic crisis and the political crisis, you said, it led them to take up arms. Did it lead them to organized activism that ultimately brought about the end of apartheid?

Pretty much, yeah. In the 1980s, this new anti-apartheid movement became much more widespread than it ever had been before. Black peoples really started working together to oppose this policy and new coalitions were built. In one example, students who had kind of had their own tradition of striking, and workers who had their own tradition of striking, formed a new group. And these kind of coalitions had not existed before. It represented a major victory for these black nationalists. These coalitions formed their own kind of standing groups, like the National Front or the United Democratic Front, and the latter, the UDF, developed really strong ties with the ANC and this kind of multi-racial goals for the country.

These movements placed new pressure on the government to change its policy. It introduced more visible forms of resistance, not only strikes as their had been, but bombing in the cities themselves. By taking these protests from the black townships to places where the whites lived, it really shattered this fiction of the peaceful successful apartheid state.

So, with growing violence and resistance becoming widespread and becoming more visible, what did the government do?

Clearly, the government had to take some kind of reaction to preserve its traditional state. It launched a new, what it called a “total strategy,” which combined repression with superficial reforms. You can think of this in the way that the United States fought for hearts and minds in Viet Nam, and it’s somewhat similar to that. In one example of this kind of reform, the government created a tri-cameral legislature which gave minority Indian and coloured groups control over their own education and health matters, but in reality this legislature was an appearance of liberalization while the white government held the levers of power.

Attempts were also made to increase the livability of townships and relax segregation in private schools, and hotels and places like this, but the prices of schools and hotel still limited access predominately to whites, so this wasn’t a meaningful reform. At the same time, the government really militarized the white society, created this sense of isolation, of the last defense, so you really got the whites rallying around the government. This was an attempt to repackage to protect apartheid, but most of the African people saw through this and the UDF, was effectively an attempt to oppose this co-optation the government was trying.

So, the government’s attempting to reform, but it’s on the surface, and the African majority isn’t really buying it. Both sides are really digging in their heels and determined to protect or win for themselves, so what happens next?

This is where you get some of the violence from the 1980s that people may remember from the news. So, alongside these more peaceful protests and strikes, the ANC revived their armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe–Spear of the Nation. This is what Nelson Mandela had led before his imprisonment, so it essentially picked up where it had left off in the 1960s and launched this armed struggle. Clashes with the government increased, and freedom fighters were using tools that we might associate today with terrorism, and some people have in the wake of Nelson Mandela’s death, such as bombing and things like this, but really these were the only tools that this disenfranchised majority of the nation had to fight this much more powerful white minority government. So, these attacks–bombings, land mines, things like this–it hurt civilians, it also hurt innocent Africans, and it became a problem for the ANC both morally and politically, but it was the only option that they really had.

How did the government react to the violence?

The government had to react, and a lot of black Africans disapproved of these new tactics. One of the things that the government did was it was funding alternatives to the UDF or the ANC, and they had things like the Inkatha Freedom Party, which was meant to divide the anti-apartheid movement. You also had the government matching violence with violence. In the 1980s, South Africa essentially becomes a police state. There are armored cars driving through townships to try to keep order, and things like this.

The National Party, the NP, had always claimed that its–

That’s the government, ruling party?

Yes, the Afrikaaner party, yes. They had always claimed that they were in charge of this peaceful, progressive state, and now, with the armored cars going through the townships this seemed like it was a bit of a lie. The problem was that neither the majority of the African people nor the well armed government could really win. So, there was a real stalemate going on by the end of the 1980s.

So, a stalemate, but somehow soon after this apartheid was abolished. How did this stalemate get broken?

This is that famous story of great leadership and good luck that we’ve all seen on the history channel and will probably be there for the next two or three weeks. Honestly, it’s true, it’s a good narrative because it’s almost impossible to imagine peaceful resolutions to this issue, but that’s exactly what happened.

Part of it is because this internal pressure combined with international isolation to force South Africa to make some changes. The economy was getting worse, the fighting was getting worse, and the Nationalist Government feels like it has to move. Under F. W. de Klerk, they decided to make some political concessions. The party would try to re-create itself as the head of a nominally democratic multi-racial state. The party hoped that this would lighten international pressure and maybe convince some moderate blacks to participate in the government. So, de Klerk enacted a number of policies, the most dramatic was the un-banning of parties of the ANC and the release of resistance politicians like Nelson Mandela who had been in prison for almost three decades.

And did this work?

Well, not for the National Party, it didn’t. These gambles backfired for the most part. The National Party gained some fleeting support, and it looked good, especially among whites and some non whites as well. But this liberalization really empowered the ANC, and really empowered Nelson Mandela, who had become this kind of international and domestic icon during his imprisonment. And so, Mandela effectively united the South African movement behind him and brought greater pressure on the government. Now, fortunately, Mandela had come to question the necessity of violence during his incarceration, so during his leadership the ANC suspended its armed struggle and redoubled efforts to reach a negotiated settlement with the National Party.

So, on both sides, there were some genuine concessions for the first time, with the ANC limiting violence, really turning its back on violence, and the Nationalist Party really choosing to democratize the government. Was that enough to end apartheid?

It took a little bit more. There was still some distrust and internal opposition, even within the two parties themselves. And so it took the leadership of Mandela, de Klerk, and a number of their associates to keep these discussions for real transition to democracy on track through this tumultuous period of the early 1990s. At a town called Kempton Park in 1994 the ANC and the National Party finally agreed to a new democratic constitution. There were a number of key innovations that kind of included these concessions that you’re talking about. The government would work with the transitional council that would oversee the move to a new democratic state. For the first 5 years, a government of national unity would be comprised of all the parties receiving enough votes for the new national assembly, so no one was left out of power. A bill of rights would permanently guarantee not only racial but also gender and sexual equality, and finally the conglomeration of homelands, Bantustans, things like this, would be replaced with 9 new provinces. This, in essence, this new constitution ended apartheid and introduced the new democratic state of South Africa that we know.

So, that was 20 years ago, and we see this really quite remarkably peaceful transformation. What happens after that?

There’s the campaign that you kind of have to do with a new democratic state, and both parties really show themselves as the parties of the New South Africa. 20 million people show up, and they vote peacefully, and everyone’s really kind of surprised by this. There were a few improprieties, but generally all of the parties approve of the results, international watchers approve of the results, and the ANC wins 3/5 of the vote, the National Party 1/5, and a number of people win the rest. And so, Mandela becomes the first president of this democratic South Africa. His associate in the ANC, Thabo Mbeke, is his deputy, and then de Klerk from the National Party is also serving.

So, really, a remarkable story after decades of segregation and repression that this democratic government elected a black African president and there was no violence after the election. It was peaceful.

Yeah, relatively limited violence, especially considering how many guns were there, how many problems still existed, and South Africa’s done relatively well since then with some policies of land redistribution, the growth of the middle class, and the growth of foreign investment. There are still some problems, but generally it is seen as a modern day miracle, a small miracle sorts.