In 2006, Keith Ellison, a newly elected congressman from the state of Minnesota, and the first Muslim elected to Congress, took his oath of office on a Qur’an from Thomas Jefferson’s personal library. Why did one of the founding fathers own a Qur’an? What was his opinion of it? And how did it influence his ideas about concepts of religious liberty that would eventually be enshrined in the Constitution?

Guest Denise A. Spellberg, author of a new book called Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders, sheds light on a little known facet of American history: our earliest imaginings of and engagements with the Islamic world, and comes to some surprising conclusions about the extent of religious freedoms envisioned by one of the key founding fathers.

Guests

Denise A. SpellbergProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Denise A. SpellbergProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Denise is a specialist in Islamic history, the history of the Islamic world, and she has written a brand new book, it’s just out, called Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders. It’s a brand new way of looking at Thomas Jefferson. How did you find out that Thomas Jefferson had a Qur’an?

Well, actually there was an article that was titled “How Thomas Jefferson Read the Qur’an,” which I wasn’t expecting to find.* Also, of course, Thomas Jefferson’s Quran was used by our first Muslim congressman, Keith Ellison, in his private swearing in ceremony. I knew that Jefferson had a Quran, but when there was the media attention over its actual use by an American congressman, I couldn’t believe it had survived. So there was the finding-out part that he owned it, and then there was the fact that it still existed. That meant immediately that I wanted to see it. But I also wanted to set it in context of Jefferson’s intellectual life. And his diplomatic life. And his thoughts about religion.

* editor’s note: link to article requires JSTOR access. Citation: Kevin J. Hayes, How Thomas Jefferson Read the Qur’?n, Early American Literature, Vol. 39, No. 2 (2004), pp. 247-261

And actually the book takes each of those topics one at a time, right?

Yes, in fact, Jefferson is probably the Founder who had the most complicated and interesting interaction with ideas about Islam, and even with Muslims. He met two Muslim ambassadors during his lifetime. He negotiated with both of them, one in London in 1786, and another one he had at the White House during—the first Tunisian ambassador to the United States, the first Muslim ambassador to the U.S., who came to Washington, and even had a state dinner with Jefferson at the White House in 1805.

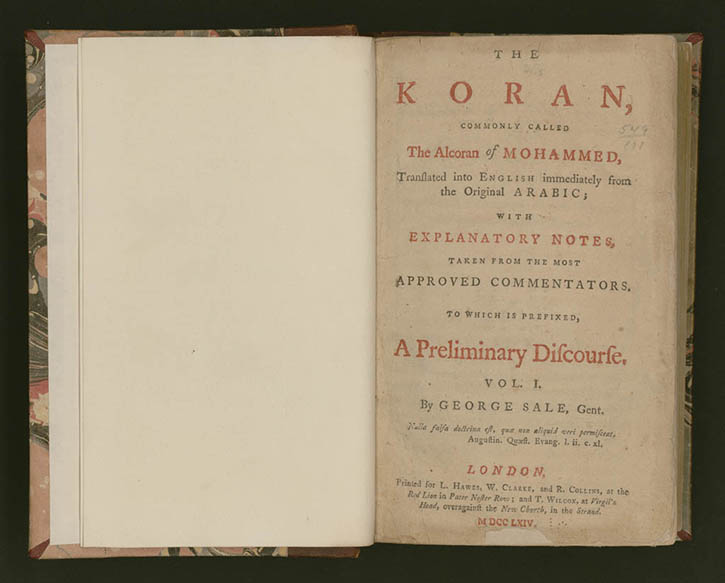

That’s a good question. Yes, in Williamsburg, we see that there’s, attested in the local newspaper, The Williamsburg Gazette, which was also the bookseller, a line written by someone else that actually says, “Thomas Jefferson, Sale’s Koran two volumes,” and it was 16 shillings. He bought it in 1765, and that’s what the records tell us from that newspaper. So eleven years before he wrote the Declaration of Independence, he was buying a lot of books, but this one was the most famous translation of the Qur’an, the only one that directly translated from Arabic into English. He knew that an Englishman had done it, and he wanted to buy it. So he had it sent to Virginia from London.

So he knew something about Islam and its holy book before he bought it, or do we know that?

We don’t know that actually, and the interesting thing is that he had this Qur’an with a two hundred page introduction, that was one of the best introductions of Islam, one of the least distorted, then available. But unlike other books, he didn’t, we don’t think or know, take notes on his reading of the Quran in 1765. And that might be because there was a fire five years later that destroyed all his books and papers. So there’s even the possibility that, this book, he repurchased. That he might have bought the Qur’an twice because it does survive and we still have it.

And almost all his books were destroyed in that fire, right?

Yes, that’s right. He says: “Almost all books were destroyed, and papers, and if it had been money I wouldn’t have thought about it.” He really lamented that. So this was a period of time when he was taking notes on important texts. He may have taken notes on the Qur’an, but perhaps they were burned. We don’t know.

Well, you argue in the book that Islam, his study of Islam and his interactions with Muslims, had a major impact on his thinking about what kind of state the United States should be, and the role of religion in citizenship. Did this study of Islam have an impact on his ideas about religious toleration? Do you think it was fundamental to his ideas of religious toleration?

Well, actually it seems as if he was very much like other Founders—some other Founders—but men of his time, in that what he wrote about Islam was not often complimentary. And sometimes it was wrong, which suggests he wasn’t a true student of the religion, although he was clearly interested. But the notion of the relationship between the religion and the state devolved upon the idea that Muslims might one day be citizens. And this is an idea he acquired by buying another book, basically, by reading John Locke, who was his hero.

And we know that Jefferson thought about Muslims as potential citizens because in 1776, a few months after writing the Declaration of Independence, he makes a note in his personal papers. He records that Locke said, “Neither pagan nor Mahometan,” meaning Muslim, “nor Jew ought to be excluded from the rights of the commonwealth because of his religion.” So even that early he was thinking about it.

And even earlier, in 1765, while still a law student (which is one of the reasons he bought the Qur’an; he was immersed in legal studies) we see he took notes for his cases based on laws from around the world. Since many people thought the Qur’an was a book of laws, and only that, he probably used it for that reason. But at the same time, he encountered a legal precedent, an earlier British legal precedent, that said that Muslims were not perpetual enemies in British legal thought. And he wrote that down, he wrote that precedent down too. So this is a world in which there were Muslims. Muslims had been in contact with the English for a very long time through trade and other peaceful means, as well as through some forms of naval conflict.

So he develops these ideas on the basis of reading Locke and on the basis of reading the Quran probably, but then, as you said, he has interaction with Muslim diplomats and statesmen. Did that change, or reinforce, his ideas? How does that impact his ideas?

It’s interesting, because at the time, John Adams talked about how after independence there was a problem with our fleets in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic commercial fleets being prayed upon by these North African coursairs, who happen to be Muslim. He and Addams interviewed an ambassador in London from Tripoli about this, trying to put an end to this kind of depredation. And the fact is Americans wouldn’t have had the money to pay for a peace treaty that would have kept them safe. And whereas Adams sees this conflict in religious terms, Jefferson saw it in completely pragmatic terms. Even at the end of his life, he doesn’t use Islam as a lens in which to feel that these pirates were anything other than lawless. All pirates were lawless. And he had written previous legislation about pirates, or losses at sea, that probably refer to the British during the Revolutionary War. So he was thinking in universal categories, but he wanted to end the conflict. So on the one hand, he thought a preemptive military strike would be good; on the other hand, he had these ideas about individual Muslims (at least theoretically) as future citizens—so they’re complications in his thought. They are kind of interesting.

There was a lot of pressure and voices calling for the United States to be a Protestant country, right?

Yes.

And you said earlier that he was influenced by ideas of toleration. Can you talk a little more about that? About where his ideas of toleration came from, and the other Founders, and was it a hard road to convince people that the United States should be founded on the idea of religious plurality?

Well, what we consider religious pluralism today was a completely radical thought in the 18th century, but it wasn’t unknown. Ideas about ending violence toward fellow Christians because of different religious opinions existed in Europe from about the 16th century. So when people started to talk about ending the persecution of heretics—their immolations, whippings, all kinds of brutal physical punishment—the earliest people who wanted to put an end to this (really in the name of Jesus and Christianity) also began to think about including Jews and Muslims in this protected status.

And out of that we see a discussion by a few people who were willing to risk their lives—to be banished, or exiled, or put in prison—to say simply that the government (and we see this with early English Baptists too), particularly the king, has no right to interfere in a person’s religious beliefs, and that religion should be separate from government control. These early Baptists suffered extreme persecution; the one I’m thinking of died in prison in England. He suggested that not just Christians and Christian heretics should be protected from the wrath of the state, but so should Turks and Jews. So we get a universal category as early as the 16th century. We see it move to England in the 17th century. So it wasn’t really just John Locke. The book attempts to point out that there are longer arcs of these thoughts about tolerance that morph into state toleration, or at least the idea of it.

Across the Atlantic, with Roger Williams, we see this also in the 17th century. And even though Jefferson never read Roger Williams, his thoughts are not unlike. The difference is Williams believed that Muslims and Jews and others would be damned, whereas Jefferson didn’t care about peoples’ salvation. What he wanted was a civil society in which there was not violence in his state or his country based on difference in religious opinion. He witnessed this persecution by Protestants of fellow Protestants in Virginia. So when he was thinking about religion and the state, he also started to think about non-Protestants. Catholics were scary to Americans in this point, but there were about twenty-five thousand of them in the United States. Jews were a despised minority of two thousand. And Muslims come up as a category, in the European context, but I think they were put together particularly with Jews because those were the two groups that Christians found the most threatening.

When we think about the evolution of universal toleration moving into Jefferson’s thoughts about rights, Muslims probably marked the furthest limits of inclusion in the American state as it was theoretically laid out. Because there was so much misinformation about Islam, there was so much fear about it. Our seamen were being captured and taken in North Africa, and yet still Jefferson insisted—as did others, like George Washington—that Muslims should be theoretically included. If they were included, then everyone could be tolerated, and everyone might eventually have civil rights. So it’s really either all or nothing.

Were there Muslims in North America in the 18th century?

Yes, in fact there were probably Muslims in America since the 17th century.

And Jefferson didn’t know that, right?

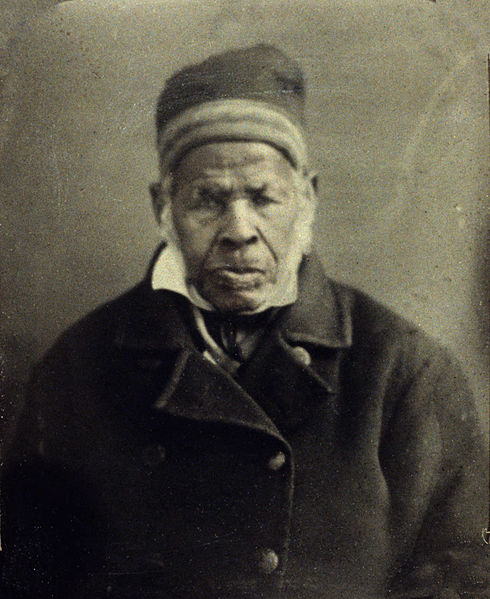

Jefferson seems strangely unaware. So all of his theoretical forecasts were probably not only futuristic, but about an imagined category of Muslims. Whereas, ironically, amongst the West African slaves taken and suffering in America (under the British and also the United States), was a segment of Muslims. A segment of believers. And we know this because some of them were literate in Arabic. They had learned Arabic before they were enslaved in West Africa, and they wrote in Arabic. But Jefferson, who was probably the champion of Muslim rights, never knew that these Muslim slaves lived in America. He never knew that he might in fact have owned some. If people retained their Islamic names, we see this. We can’t say it for sure about Jefferson, but Washington, who was not far from him, on his list of taxable property, we see two names of women named Fatimer and Little Fatimer. Fatima is the name of The Prophet’s daughter. So Washington, who actually also had these beliefs about religious liberties as a universal (and who also listed Muslims in that category) ironically owned Muslims and didn’t see that these ideas about rights were in conflict with then notions of race and slavery.

That’s the biggest contradiction in all of this. You can map out rights, you can talk about a future with Muslims in the country, but at the same time you’re oblivious to the Muslims who were there.

And that you owned them, and they were slaves.

And you owned them! The idea of rights, of any kind, is obliterated by this slavery institution.

What are the implications of this research for today?

Well, in the afterward of the book, I try to talk about the fact that (as in the 18th century), Muslims, Jews, and Catholics were often linked together as outsiders. Once the theory of civil rights and religious liberty included all three groups, they were technically accorded these rights. There’s no religious test in the Constitution, freedom of all religion is guaranteed in the First Amendment. But in truth, Jews and Catholics struggled into the 20th century to realize those rights against amazing bigotry. I think the difference is Muslims now are in a position that Jews and Catholics once were. They are a group that is often targeted as not fully American. When we have a diverse and dynamic American citizenry, who vote, who live here, and who have been guaranteed rights (not just in terms of our documents, but historically). Those who would suggest somehow, that American Muslims are not full citizens, probably need to learn more history.

I think for that reason, this research is really important. To see the origins of the state that we live in included this very broad, universal concept of religious toleration and rights.

Right. In fact this is essentially the principle that supports inclusion. So you’re either going to include everyone—Jefferson even mentions Hindus in his notion of those who should be included, not just with religious liberty, but actual rights and potential access to political office. In fact, when we see Congressman Ellison elected, I don’t think it was in spite of his religion, I happen to think it was because of it. That there was a place for that—

—For electing a Muslim.

For electing a Muslim. That’s the logical outcome of these prescriptions from the 18th century.