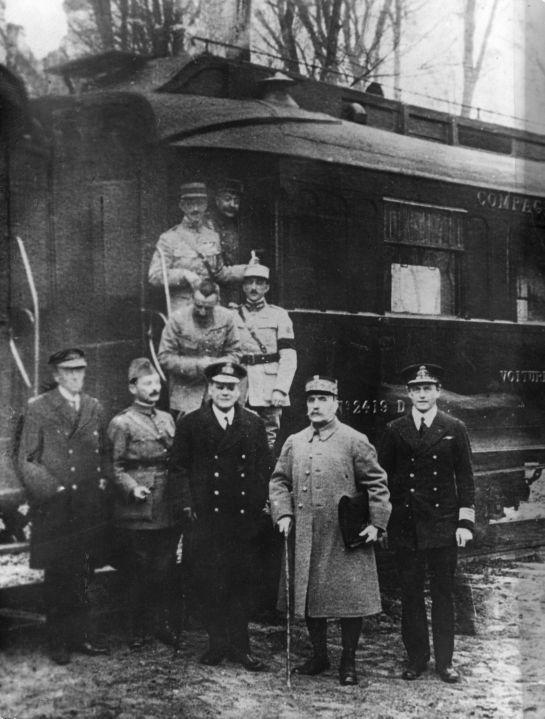

On November 11, 1918, the guns fell silent in Europe as the armistice with Germany ended World War One. World War I changed the face of Europe and the Middle East. The war had brought bloodshed on an unprecedented scale: tens of millions of people were dead, and millions more displaced. The German and Russian economy were in ruins, and both nations rebuilt in different ways before meeting on the battlefield again a generation later.

Guests

Charters WynnAssociate Professor of History, Director of Normandy Scholar Program on World War II, UT Austin

Charters WynnAssociate Professor of History, Director of Normandy Scholar Program on World War II, UT Austin David F. CrewProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

David F. CrewProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

In the first round table that we did, which focused on the Middle East and the Balkans, both of our guests mentioned the agrarian nature of the First World War and hinted that when the food supplies began to run out in Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire which were the other two Central Powers, the will to fight waned. And that was when the writing was really on the wall for the wars. Is that a fair assessment to make about both Germany and Russia? Dr. Crew, why don’t we start with you?

[DC] I think that the food problem was definitely an important and growing problem in Germany. But I would also put it in the context of the growing perception that the Imperial government–Wilhelm II’s government, was not doing what it should be doing, or was not doing an efficient job of trying to distribute food fairly. There was the growth of an enormous black market. Maybe the way to look at it is that Germany was under a blockade by the British. The British Navy had installed a blockade, and that increasingly affected food imports as well. So it contributed to domestic unrest.

And that transmitted to the front as well, because people wrote millions of letters back and forward. And then people knew what was going on in the home front. And so there were already food riots, mainly women, younger boys and girls at home, waiting hours in line for food that maybe didn’t arrive. And then by 1917, those morphed into massive strikes.

Dr. Wynn, what was the situation in Russia, which, of course, had kind of stopped its war effort a bit earlier, because there was a revolution?

[CW] Arguably the main spark for the February Revolution, which overthrew the autocracy, were food shortages. Russia is a country that was made up of 80% peasants. Actually. the harvests during the war were not as bad as one might think, given food shortages that ultimately affected St. Petersburg, which was renamed Petrograd during the war. Certainly many of the villagers were conscripted into the army. So there was something of a labor shortage. But the major problem with the food was that problem of transportation, getting the food to the to the army, getting the food to Petrograd, and coupled with other problems, fuel shortages and others. It sparked major unrest culminating in the overthrow of the autocracy in February 1917.

When the war comes to an end, how does Germany attempt to rebuild itself? It’s lost its government, or at least the Imperial portion of the government, and like the Ottoman Empire, as we discussed previously, the terms are imposed upon it from outside as to what surrender is going to entail. How does that go over?

[DC] Not very well.

As soon as the terms of the Versailles Treaty, or what’s going to be the Versailles Treaty becomes public, there are massive demonstrations in Berlin and elsewhere in Germany, because of a couple of things, I think. One is that Germans had really, during the war, been misled about the military situation – there was heavy censorship of the press. But more importantly, I think, is that we have to keep in mind that in the East, in the war against Russia, then it appeared that sort of in the 11th hour, then the Germans had scored an enormous victory. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was seen as a great coup by the by the Germans. And they finally gained access to Ukraine as a consequence of that, and the food that they desperately needed. But it was too late in the game. They were able to transfer 40 divisions from Eastern Europe to Western Europe. But it was all too late.

I think in the public opinion–Hitler himself said that he was recuperating after a gas attack in a hospital in Eastern Germany, that this, you know, came like a bolt of lightning. Those weren’t the exact words, but that it was a shock. And it was a shock to, I think, many, many Germans that they had lost. You have to keep in mind that Germany was not occupied directly at the end of the war. The armistice didn’t provide for that. But above all, it was the terms of the treaty, which we could talk about as we go on, and the fact that the the German delegation at first had no input into this whatsoever. They were kept sequestered and it was a sort of, you know, slap in the face that, in the very place–The Hall of Mirrors and Versailles where the German Empire been declared in 1871–now, the peace was imposed upon the Germans and their only choice was to reject it and then be occupied by the allies.

How did the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk impact Russia? What were the terms of rushes agreement to end hostilities with Germany?

[CW] Well, after the February Revolution, February of 1917 that I mentioned, nine months later the Bolsheviks seize power and part of their appeal to the population was that they would get out of the war. They had a simple slogan: Bread, peace and land, and so peace was central to their appeal. They were the only major party that wanted to get out of the war, no matter the terms. The Brest-Litovsk treaty was signed in March of 1918, and basically, Germany already occupied all that territory. So, there was the hope, misplaced does it prove to be, that the revolution Russia would spark revolutions in Germany and other countries, that would ultimately nullify the treaty. And, in fact. in November with the defeat of Germany, the treaty is nullified, and ultimately during the civil war that follows Russia will gain much of that territory that was given up in the Brest-Litovsk Treaty.

So which government signed the treaty?

[CW] It was Bolshevik. That’s very contentious, many many Bolsheviks were opposed to signing the treaty, but in Lenin’s very famous phrase, Europe is pregnant with revolution. We’ve already given birth and we need to protect this revolution.

[DC] Well, just sort of follow up a bit more on the question you posed was that the way the war came to an end in Germany was confusing to lots of people. But it also opened up the possibility for creating scapegoats because there was a revolution at home. Two myths were created, I think almost immediately. One was the famous “stab in the back” legend, which basically argued that the the German soldiers had stayed true to their duty to the last minute, most of them, but it was the socialists and the Marxists and the Jews at home who had fomented discontent and had undermined them — had literally stabbed the military in the back. Which was, in terms of stabbing the military in the back, it was completely untrue–there was a revolution which is actually started by sailors in the North Sea ports, and then spread to sailors and soldiers in the rest of Germany, and then into the civilian population. But it’s also true that after the Ludendorff Offensive in the spring of 1918, German soldiers were defecting and large numbers were either not going back to fight at the front or clearly could not be relied on to launch another offensive and the Allies gain the most ground that they had in that period.

And I say all of this because it put the successor government–what eventually became the Weimar Republic and its statesman in a pretty awful position because they were tarred with the brush of being the ones who signed the treaty which no German liked, including politicians in the Weimar Republic. And it became all too easy to associate Weimar with this ignominious treaty, and with the horrendous defeat.

Let’s talk about the Weimar period, because it’s frequently in history brought up as an example of almost a failed state, if you will, that it was ineffective, that it never really governed Germany well, and that it basically lent itself to the rise of fascism in the 30s. Is any of that a fair assessment?

[DC] I think the part that says it’s often characterized that way is a fair assessment. [laughter]

One of the things that I always try to do in my class is to say, look, the Weimar Republic lasted longer than the Third Reich. [CW: good point] The Third Reich was incredibly destructive, and head, you know, horrendous consequences for Germany and for World History. But, you know, one good comparison would be to say Mussolini, he marched on Rome and took power as early as 1922. Hitler tried to do the same in 1923 and failed miserably. Weimar had to deal with multiple crises, some of them inherited from the Wilhelmine monarchy, for which it was nonetheless blamed. Some of them intensified by what it did. But in the immediate aftermath, up until about 1923-24, there were problems of the defeat, huge loss of territory, forced demobilization at a rapid rate required by the allies, and then hyperinflation that was unprecedented. That created a lot of damage, undoubtedly, and it really polarized the society.

But nonetheless, the Weimar Republic then went into a period of relative–I emphasize relative–stability from 1924 to the onset of the Great Depression. And all of the effects of the lost war played an important part in the rise of Hitler to power. But we have to keep in mind that after 1923-24, when Hitler decided that they were going to the Nazis were going to fight elections, they never got more than about 4-5% of the vote, so they were confined to the margins. It was the Depression, I think, that created the next new crisis that gave the Nazis an opening. It’s a complicated story, but it’s unclear to me that Weimar could not have survived. I mean, it’s unlikely, but it might have survived.

Looking at Russia during this period, they’re fighting their own civil war. Is the specter of would have what World War One could have done if had they stayed in longer, or something that was lost important in the Russian psyche, or is it just sort of pushed aside in favor of internal politics? What then leads Russia back toward the war march in the 30s?

[CW] So, are you asking if if the memory of the war was pushed aside?

I guess the idea of the war as something a missed opportunity and unfulfilled dream, something that needed to be redeemed. I know, for example, in the German imagination redeeming the war loss played huge in the march toward the Second World War. Was there any of that in Russia or not really?

[CW] Not really. It’s the revolution that was central to the psyche of Russians both for and against the Bolshevik regime. It’s the signing of the Brest-Litosvk treaty that’s the final straw that leads to armed opposition to the Bolshevik seizure of power. The civil war that you mentioned, part of the Civil War experience was 15 foreign nations intervening in the Civil War on the side of the anti Bolsheviks, the Whites. That was something the Bolsheviks used to portray themselves as “the true patriots,” that they’re not lackeys of these foreign Imperial governments as they would portray it.

But World War One was something that is not generally appreciated. Russians suffered more losses than any other country during the war. It devastated parts of the Empire where they engaged in scorched earth policy as they were retreating, especially during 1915. But they were not allowed to have veterans organizations like elsewhere in Europe, World War One veterans. There was no commemoration, to this day. You started the podcast off with the armistice–Russia does not recognize the armistice. That’s not a holiday in Russia. So, its experience was quite different than the others.

I would just add that it does play a significant role during the war, but as I said, it suffered major losses. But it’s all forgotten. It’s part of the past. I think, even today, most Russians do not appreciate what they experienced, because Soviet historians did not emphasize the war. Foreign scholars were not allowed to really do research on the war until until the collapse of the Soviet regime in 1991. So, it’s still a relatively understudy part of Russian history and their experiences during the 20th century. It’s certainly World War Two that is the major focus and arguably legitimized the regime in a way nothing had before.

So, the Civil War in Russia is settled about when? The mid-20s?

[CW] Oh, no. It begins in the spring of 1918. And arguably, by the end of 1920, it’s over.

Okay.

[CW] In Central Asia, it will continue longer than that. But it is generally over by the beginning of 1921, they’ve basically recaptured much of the former Empire. You know, not the Baltic states, and not Poland, the part of Poland that was part of the Russian Empire, but it’s over by then. But the country is in utter ruins, the economy is completely collapsed. It’s something like 15% of its GDP in 1913 is what the industrial output was in 1921. So they’ve emerged victorious, but there’s mass unrest with the Bolshevik regime. And there are serious, serious economic challenges, partly as a result of their own policies of grain requisitioning–taking grant from the peasants. Again, the food problem that we started off with was a major issue during the Civil War. But there will be in 1921 a massive famine in which some 5 million Russians die, and would have been even worse if America hadn’t provided aid during 1921.

[DC] I could come in and say a little bit also in comparing to the memory of, or the interacting with World War One in Germany. That’s really a hot button issue, clearly, its presence, especially, obviously present in terms of the outcome, of the dislike, the hatred, even, of the Versailles treaty. Mentioning Poland, that’s a huge loss of territory for Germany. Poland, after the late 18th century, had just disappeared from the map of Europe, swallowed up by these three great powers of which Prussia and Germany, the Empire, was one of them.

And so, those are all issues, the way I would look at it would be to say that this is a highly contested memory, right? And you can sort of focus in on towards the late 1920s, you get the appearance of major literature war novels and other literature on World War One. Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front is the most famous. It presents a certain despairing view of life on the front, which the Nazis hate, right? When it’s made into a Hollywood movie and shown in Berlin in 1930, Goebbels makes sure that it’s so completely disrupted that they have to shut it down.

I would say that the memory of World War One plays into the Nazi period, obviously, in important kinds of ways. But above all, it’s this sense that you see almost to the very end amongst military leaders, others we don’t want a repeat of November of 1918, in other words, German revolution. I lived through that. And that’s just so shameful. We can’t possibly have that. So we’ll go down in flames rather than have that happen.

One of the things that listening to Charters I think is important is that World War Two looms very large in contemporary European memory. But World War One is also extremely important, right? But it’s undergone sort of a metamorphosis that I don’t think that World War Two is ever going to undergo. And that is, it is now a European memory. And if you go to, you know, there’s a major Museum of the First World War in the Somme. And the narrative there’s constructed in terms of all sides are represented, and everyone’s suffered, right? And this was a colossal mistake that everyone paid for. I can’t ever see a similar kind of narrative being developed around World War Two.

The interesting thing about the the notion of the war being a mistake, and not only a mistake but it was it was incredibly traumatic. I mean, the field of trauma studies comes out of World War One, the notion of “shell-shock” you know, people who are literally rendered stunned by by the shells exploding, comes out of World War One. And yet, particularly in the 30s there’s almost this march toward another inevitable military conflagration which if one considers the war a mistake is almost counter-intuitive…

Well, I would say two things. Number one, I think that it’s not that everyone’s marching in lockstep in the same way on this path. Hitler and the Nazis, definitely, and the German general staff. Obviously Germany under Hitler is on a path to fight another war, to prepare for another war to overturn and completely erase the results of the First World War. But that doesn’t mean they want to refight World War One. Everyone’s afraid of re-fighting World War One. It seems that with blitzkrieg–even though that’s sort of manufactured as a concept after the successes–that it seems that Hitler’s found a formula that would actually allow a shooting war that’s not going to have the same kinds of consequences and costs for Germany.

Two scenes to contrast would be, however staged they might have been and partial in many ways, the crowds on the street in August 1914 cheering and expecting a quick German victory in Berlin and elsewhere versus–basically Goebbels can’t get anyone out in the streets to do this in September of 1939, because the specter of world war one shows up when it looks as if Germany’s going to actually fight use its weapons. But when Hitler, you know, defeats Poland in a matter of six weeks. And then, I think, even more than that, in some ways achieved in May of 1940, the complete defeat of France and the occupation of Paris that the Imperial German Army had never been able to do in World War One, then that ghost of World War One fades into the background.

But it’s with Stalingrad, certainly with the invasion the Soviet Union after about December–definitely with Stalingrad it comes back and that you know, in Western Europe, you can see graffiti written on the wall by resistors or people who are just against the Germans, Stalingrad = Verdun. Verdun, as we know, was a complete disaster of 1916.

Let me ask a similar question about the Soviet Union, then. Because you mentioned at the beginning of the war Hitler and Stalin had agreed to divide Poland So what was the sort of thinking there that of acquiring more territory, considering that the Russian population also been through a lot in the previous war?

[CW] And in the intervening years between the war and the outbreak of World War II. There wasn’t a march towards war, except in Germany. I think it’s fair to say. Not only was France and Great Britain desperate to avoid repeating World War One and was very traumatized by it as you mentioned, so was Stalin’s Russia. It thought war probably was going to come eventually with Germany, but it was desperately trying to delay that. Stalin was not convinced after Munich in particular that Western Europe would stand up to Nazi Germany and that their goal was to leave the Soviet Union alone against the Wehrmacht, the German army. And Germany is determined not to have to fight a two front war like in World War One, and they propose this Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact. Stalin leaps upon it. He thinks this is going to spare the Soviet Union from war.

He anticipates that Germany will attack Western Europe, and it will be a repeat of World War I. That it will be a long drawn out war, both sides will be depleted, but that the Soviet Union will be rearming itself at this time. And when war does come, they’ll be in a much stronger position. When France falls so quickly, as David mentioned, Stalin is just stunned and never really comes to grips with it. The reason that Germany enjoyed such enormous success during the beginning of the war is because Stalin refused to heed warning after warning that this was coming. That Germany was able, with 3 million troops on the Soviet border, to launch a surprise attack defies imagination.

One can come up with some reasons why why Stalin thought if they hadn’t invaded by by the middle of June they weren’t going to invade, that was too late. The heavy rain of the fall were coming, and then winter. Stalin believed that Hitler wouldn’t repeat the mistakes of Napoleon, right? But he was wrong. And the German successes during the first months of the war are stunning. I mean, it’s like a catastrophic defeat. It seems like the Soviet Union would never be able to survive it. They basically lost their entire army during the first six months of the war. Germany has complete air superiority, it’s an utter disaster. Yet, they ultimately prevail for reasons we could go into if you’d like.

So the specific events of World War II I think we’ll have to leave for for another podcast, possibly in commemoration of the an anniversary there. But the ending of the Second World War, which sought once again saw Germany defeated, did not have the same lingering impact, the sort of resentments–at least from this vantage point, several decades later–that the end of the first war did. What was different about the settlement to the first war, as opposed to the second?

[DC] I would say just about everything.

Although, you know, I would say that the end had a very important lingering impact. It was just a very different lingering impact, above all, in the form of the occupation and division of Germany. I mean, I think the major differences are, number one, the Red Army is in Berlin, the Allies have agreed that they won’t accept anything less than unconditional surrender, and they also are committed to a period of occupation of Germany that’s indeterminate with, amongst other things, the goals of eradicating all traces of Nazism, Nazi ideology from the political culture. And so, Germany, in effect ceases to exist as a nation state between 1945 and 1949.

And after that, you get two new, very different successor states that … their early history, and I would say, much of their history is, is determined really by the Cold War and the superpowers. So,the political landscape is completely different than it was. It leaves absolutely no, or not as much room, shall we say, for for any kind of conspiracy theories about how Germany lost the war. Germany was defeated. You will still get, you know, Germans saying that the German soldiers were the best in the world, and they were just overwhelmed, particularly by the capacity of the United States to turn out all that war material and the troops sent there. And, you also get a very divided memory of World War II because of this division between West and East.

Russia in particular, in this case, they come up victorious, even though, once again, they probably bore the majority of the civilian casualties during the war. How does that play out on the homefront?

[CW] Well, they do lose an enormous number of civilians as well as soldiers. Most people in the West–in the case of World War One and in the case of World War II–think it was one it was decided on the Western Front. And that’s the focus. David and I are part of the program, the Normandy Scholars Program, we go to D-Day, and that’s seen as the breakthrough in World War II.

In fact, 80% of all German soldiers died on the Eastern Front. Ultimately numbers have gone up over time, but it’s now generally accepted that 27 million Soviet soldiers died during World War Two–excuse me, citizens–about 17 million of them were civilians. The German policies towards the civilian population was one of atrocities and, in, the case of Leningrad starving the population to death. So, the memory of World War Two lives on very powerfully in the Soviet Union. Virtually every family lost somebody during the war. When I first went to the Soviet Union, 1982, it was common to see newlyweds go to a World War Two Memorial. That was part of the just the routine of a wedding day. So it’s a very, very powerful memory in the former Soviet Union.

It emerges as a superpower, the other great superpower. It occupies Eastern Europe, and has this empire outside the Soviet Union. But the country, like in the case of World War One, is utterly devastated by the war, not just the the population losses that I mentioned. But the economy is in ruins, a very different situation than the United States that emerges without foreign occupation, but it’s the other great superpower.

The Soviet Union sees the loss of Eastern Europe actually, as one of the traumas of the of the war, that Gorbachev gave this away. In Gorbachev’s very famous statement, he said, and I’m paraphrasing, that the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century was the loss of Eastern Europe or the loss of the former Soviet Union. And so that’s another issue but the the loss of great power status that the former Soviet Union has endured is one of the lingering memories of the war, too.