In 1885, the world’s attention was focused on a series of grisly murders that took place in the otherwise quiet town of Austin, Texas. Several African-American women were murdered in the middle of the night, leading the press to dub the unknown assailant “the Servant-Girl Annihilator.” Some even went so far as to speculate that Jack the Ripper was the same person.

Lauren Henley describes the events of 1884-85, but also discusses how these murders tell us something about the uneasy racial history of the postbellum south, and also asks what drives our fascination with serial killers and unsolved mysteries.

Guests

Lauren HenleyDoctoral Candidate in History, the University of Texas at Austin

Lauren HenleyDoctoral Candidate in History, the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

What happened in Austin in 1884 to 1885?

On December 30th, 1884, Mollie Smith, a relatively young, black woman, was killed. She was killed in her bed, late at night, and no one really knows what happened. She worked for an insurance agent from Galveston, and unfortunately, her common law husband was injured in the head. He went to her employer’s house at about three am, knocked on the door and said “Mollie’s gone.” Of course, this started a lot of controversy: his employer, a white man is nervous and is concerned. They go outside and they find Mollie’s body.

Then, on May 7th, Eliza Shelly is killed, also a young black woman. Unfortunately, she has some young kids. They witness her killing. Then, just three weeks later, Irene Cross, a black woman, is also killed, and she is alive for about two or three hours after her first attack. She then succumbs to her injuries. Then, the summer passes, really nothing too extreme happens.

Then on September 1st, things get a little crazy, because an eleven-year-old young black girl Mary Ramey is killed. Her mom, Rebecca, is sandbagged, and Mary, like Irene, was alive at the time reporters arrived on the scene, but she died about an hour later. Then, at the end of September, Gracie Vance and Orange Washington, a black couple, were killed in their house. There actually were four people present, two boarders they were keeping: Lucinda Boddy and Patsey Gibson, and those two were just injured.

So, you have in the span of about nine months, a handful of black women, a black girl, and then a black man, who all murdered, arguably under the same auspicious. Interestingly enough, Christmas Eve, 1885, two white women are killed. One is seventeen-year-old Eula Phillips, and one is forty-year-old Susan Hancock, and they are killed within a few hours of each other. Though both of their husbands are eventually charged with their crimes, one is acquitted, one is convicted, somehow those two get looped in with the previous six. Austin coins the term the “Servant Girl Annihilator,” to explain who committed these murders, and it turns out that no one was ever caught, no one was charged, and the crime still goes unsolved today.

How did the city react to these murders?

Well obviously, panic. The city is on edge. There is a level of interracial cooperation that really doesn’t exist in other places in the post-Reconstruction era South. It just can’t. The city is really unique in that they call for everyone, black and white, men and women, to arm themselves. Literally with guns. People stop socializing in the evenings because they are too scared that they are going to come home and see that their women are killed. Every black man in the city is questioned at some point in relation to these murders, but none of them are ever arrested and held. Interestingly, a sort of cultural artifact emerges, which is a little jingle that comes out of these really violent murders. They sing: “Get thee a gun, oh Serving Girl, and keep it by thy bed/ Take aim upon the ruffian, and fill him full of lead.” Clearly, there is an interest in the city just stop, stop, whatever it is that’s going on and figure out who is doing this.

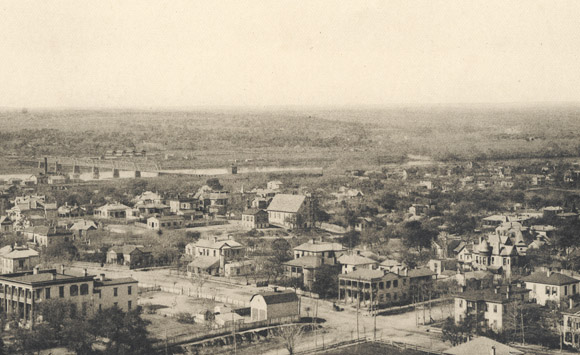

Austin, of course, is at the time, a sort of small, western, fringe city, there’s only about 12,000 people in town with only thirty police officers. The city government at the urging, or really mandating, of the Austin Daily Statesman, hires a private detective to come down from Houston and actually solve the crimes. That doesn’t work. At all.

I’ve never heard anything about this particular case. Is this one of the first instances of serial killers in the U.S., and how do we think about what qualifies as a serial killer? How do they come to this decision that its one person?

It’s interesting in that a lot of people do think that this is the first American serial killer. I think part of the difficulty in discerning that for sure is that the term itself “serial killer” doesn’t enter the American lexicon until the mid 20th century. When this case is happening, the “Servant Girl Annihilator” is as close a term as people in that time can figure out, and yet, a lot of people also think that the same person who committed these murders is Jack the Ripper. I don’t buy into that theory, but it is an interesting one.

Part of the difficulty in studying serial killers is exactly that terminology. One “mandate” that has been universally accepted now about who qualifies as a serial killer is that there have to be defined “cooling-off periods.” How long that is, what that is, why that is, no one can fully explain, but the thought being that the average person would need time to “cool off” from a crime, think about what they’ve done, and then serial killers tend to do it again. Also, there is the idea that serial killers kill people in a particular pattern. At this time, the pattern just seems to be young, black female domestic servants, but then we have two white women, too. So, it’s not quite clear why those two get looped in, other than the fact that the actual way that they are killed seems to be relatively similar. So, serial killer, yes? But, can we confirm that it’s not multiple people, no.

One way that I get around that tension is that I actually don’t use the term “Servant Girl Annihilator” at all in my writing. I focus on the victims, and not on the perpetrator, because you’re exactly right, we don’t know. It could have been a series of copycat crimes. It could have been just a spattering of urban angst, perhaps. We don’t exactly know who did it.

Why do people think its Jack the Ripper? Is it just a sort of speculation that they never figured out who Jack the Ripper was, so he could be anywhere?

It’s a nice story, right? If its Jack the Ripper, the thought is that he “perfected” his “talent,” his “penchant” for killing women who have deemed themselves sexually problematic. Jack the Ripper’s crimes happen to start in 1887 or so, which is just after these have ended. Of course, he’s in London, there are a few boats that are traveling that way. It’s a nice story, but does not seem to fit the crimes though.

I want to go back to what you said before about how Austin is kind of unique in that the racial dynamics of the city are very different. Can you talk a little bit about how post-Reconstruction ideas of racial hierarchy play into local understandings of these murders?

Sure. Obviously as you know, the Juneteenth Celebrations start in Galveston on June 19th, 1865, and as a result, there is an upsurge of black people, recently freed, who are moving towards other parts of Texas, including Austin. And so, there developed some really robust black communities in town, Wheatville, Kincheonville, Clarksville, Masontown are all well-known black enclaves at the time. There are relatively centralized spaces for black people to congregate and to just build community, and we can’t forget, obviously Texas was once Mexico, so there is a large Hispanic population as well. Though the city is not without segregation and is not without racial animosity, because of course it does exist, there are some really unique spaces in which interracial mixture does take place. One of the most common places is Guy Town, which is the vice district of the city. It is bordered by the river on the Southside, then Congress at Guadalupe and then to today’s Fifth Street.

Is it called Guy Town because it is for men to go?

Precisely for men. Precisely for men to go cavort with some interesting characters, mostly prostitutes, not surprisingly. But also, where the bars and taverns are there’s lots of fighting going on in Guy Town, seedy part of the city. But 5% of the city’s female population aged 18-44 are in fact prostitutes. So, it’s a thriving business. Who wouldn’t want to have fun down in Guy Town? Because Guy Town is its own little space, and, for example, the young white woman who was killed Eula Phillips was thought to maybe hangout down there, and is maybe engaging in some salacious behavior with the city’s elite, there are some rather interesting connections between Guy Town and then the rest of Austin.

When these murders break out, Austin is already in a unique interracial space, and there’s a serious debate going on in the paper, which is, I would say representative of the larger public consensus, which is that “Woah, these murders are way too good to be perpetrated by a black man, he would get caught, there’s no way. But they are way too animalistic and way too violent to be done by a white man.” So, what gives? The murders are so distinctive that they don’t actually ever fit within a stereotypical understanding of who could have done them, and at no point ever, of course, is there any idea that it could have been a woman, multiple women, or anyone who is not black or white, namely who is Hispanic. The city doesn’t know what to do with its own racial understandings of who could do this and then the reality of what’s going on.

Of course, initially, there’s a major thought that everybody who is white is going to be safe, because the first people who are killed are all young black women. But then the paper starts to think, “well, what if the killer just gets a penchant towards the ‘other race.’” Lo and behold, perhaps that’s true. We don’t actually know if it is true.

Can you talk about some of the complexities with studying a serial killer, if you want to use that term, because there is so much uncertainty with this case, so much that you don’t know, so much that you have to rely on other people’s interpretations of what fits that particular model? What kinds of methodologies do you employ to sift through this material?

As I said, first things first, I study the victims as opposed to the perpetrator. That way, “serial killer” becomes less of a loaded term and more so a place for me to understand the intersections of various people’s lives. Though they come into the historical record through a level of trauma, I actually want to understand “who were they before?” In this particular case, “who were they after,” because there is a really interesting past life that comes as a result of these crimes. Then, I do something that I think some historians would think is a little problematic, which is that I actually look at the way the crimes unfold at the moment in which they took place. I don’t look to draw patterns or connections like we get to do today, with the privilege that we have of studying past serial killers. Instead, I want to know “what happened from December 30th, 1884 until May 7th. How did the city understand what’s going on and how are people’s coming to terms with what’s happening?”

What makes serial killers in particular, as opposed to some other forms of violent crime, a really interesting mental space to study is that the first person killed by a serial killer is never understood to have been killed by a serial killer until someone else dies. For the perpetrator, it gets to be a unique space of buying time, to act again or to not act again, and to plan another crime such that linking the first one becomes the normal socially accepted thing to do. When Mollie Smith is killed, everybody thinks it’s her boyfriend, and then everybody thinks it’s her ex-boyfriend who is from Waco. The papers are reporting that it’s a love triangle gone awry. William Brooks, the ex-boyfriend, has come down because he’s jealous that she’s living with Walter Spencer. He’s the one who’s done this. The paper is pretty sure that’s the case: a jury of inquest is convened. They find out that’s not what happened, but they don’t know where to go from there. So, they stop, and it’s not until Eliza Shelly is killed that the paper looks back and says “Well, there was another black woman a few months ago who was killed in a similar war.” But at that point, five or six months have passed. The serial killer idea took a long time to catch on. I think today we collectively understand at some point, a serial killer has killed. Whether that is two people, or three people, or four people, we collectively come to a consensus about what that is, but historically how news traveled, I think it took even longer to make that connection.

When you talk about that you want to “center the victims,” how do you write, how do you craft a narrative that allows you to talk about all of these things, but then you’re dealing with the victims themselves as the subjects versus the perpetrators?

I actually center the victims by one simple way, which is that I refuse to say how they die. I just won’t. I will gladly quote the newspaper articles and I tend to do it at length, in these long block quotes to let someone else explain it, but I’m not going to reinscribe that violence into my own words. I don’t think that’s fair to these women. What that allows me to do then, is to take the focus off of the moment in which they died and instead they pull it into the relationships they had before, the families they left behind, where they lived, what social networks they had. I can use things like city directories to figure out, “well they might have lived here, but who else was in their immediate circle?”

When Mollie Smith is killed, the first thought is that William Brooks uses the fact that he had been at a dance party that whole night serving as the emcee until like four am to show that there’s no way he could have done it because he’s at this party. Lo and behold the black community in Austin agrees with him. They were like, we were having a great party, he was there, don’t worry about it, we can vouch for him. And so that’s a space where, despite the trauma, we can see the development of a really robust black community that’s going on in town. I’m interested in seeing how these women fit into that as opposed to how their lives were just ended. Otherwise, it gets to be a really sad thing to study, the ending of black women’s lives, particularly younger black women. So, I just don’t write about it.

Can you speculate as to why historical or fictional serial killings fascinate people? I really appreciated the point you made that you are not going to inscribe that violence in your work in the same way, and I think in some ways people are fascinated by violence and violent action. Is this something that you think is a factor, or why do you think it fascinates people in this way?

I think you’re definitely on to it. It’s precisely the fact that they are violent, and yet the thrill of the unknown in a historic or fictional serial killer is totally enmeshed in the irony in the irony that it is 100% known. It is over. Historically, they are dead, including the perpetrator. Fictionally, well it could never actually happen is what we tell ourselves. We like them in the past because we get to experience all the fun, and excitement, and thrill, and terror, and horror, and fear, without actually experiencing any of those things in reality. You don’t like the way the story is going? You close the book, you turn off the TV, you close the magazine, you leave. That’s it. The idea that a serial killer can be contained in the past is really alluring to a lot of people in a way that an actual serial killer in real life, in real time is absolutely terrifying. I think studying this case in Austin in the past in the way that I do allows me to understand more about why contemporary serial killers do evoke a level of fear that we can’t really replace.

I think that makes a lot of sense, especially when you think about shows like “Criminal Minds” where you have these very abstract notions of what a serial killer is versus someone like the D.C. sniper, I have family from D.C., that was a very terrifying time to be living there. How do you think about the contemporary aspects of this case that you think are still relevant?

So, I think you’re hinting at the larger thing that’s going on, which is this modern glorification of what I call “the grotesque horror.” Things like “Criminal Minds,” “How to Get Away with Murder,” “Law and Order,” “Bones,” there are so many shows today that are all about murder. The actual literal ending of someone’s life, but only in fiction. If you couple that with the modern news cycle, in which we loop videos of people dying, over and over and over again, often times, its only new if there’s another angle we get to see. But it’s the same death. As a result, we end up with an oversaturation in society of interest in murder and actually watching someone die. Not surprisingly, the Servant Girl Annihilator case has also reached interesting, maybe a resurgence, in the last few years in that people are really captivated by it. There are really a handful fiction books out that have rewritten the story to include the actual person who named “Servant Girl Annihilator” as the term, is O. Henry, a famous author – founder of Rolling Stone, lived in Austin for a while.

There are a lot of fiction books that create a narrative around him, and talk about how he would have understood these murders, which is problematic. They give these women lives that basically justify their deaths, which is also concerning. There are quite a few local authors who like to write about these crimes in magazines like Austin Monthly and things like this. There’s also a PBS Special that tries to figure out who they think did it, and they conclude that it’s a young man named Nathan Elgin, who is a young black man who simply was fighting a black woman at a bar, gets arrested for that, and the police notice he’s missing a toe. One of the footprints at one of the crime scenes was also missing at a toe. When Nathan goes to jail, the murders stop, so they think its him.

What is perhaps the most fascinating to me and brings the nexus of the contemporary together with the past, is that there is a walking tour podcast of the murders. You can pay for it, which we get into the issue of commodification versus commemoration. You can walk around to the sites where these women were killed, you can stop in the Austin History Center and view the police record of every black man who was pulled into this. You can go walking around to experience their deaths if you want. I do think there is a sort of concern, maybe, with the continued violence on these young women and maybe profiting off of their stories, because ultimately, we want to understand them as people, not as simply murder victims.