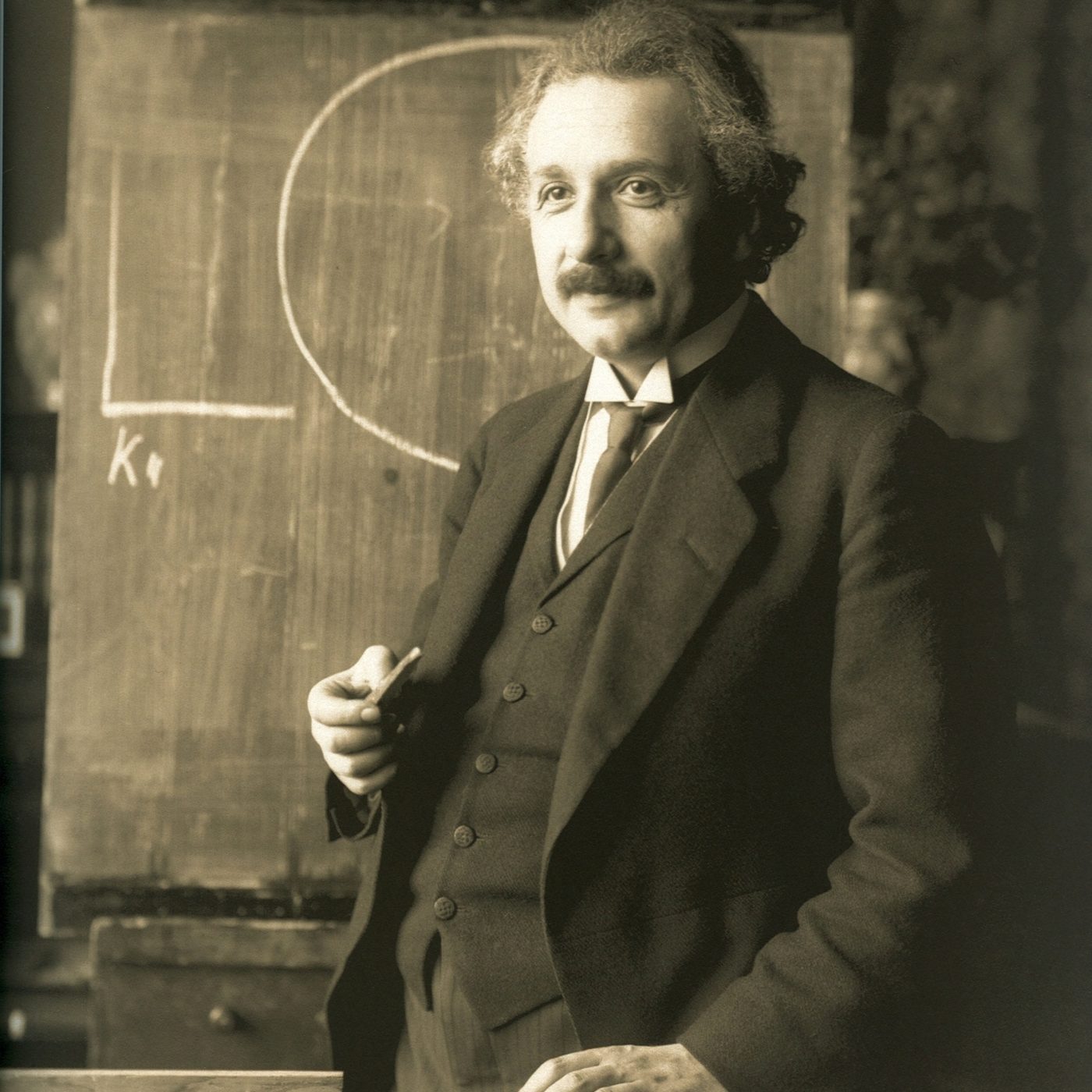

The subject of endless speculation, fascination, and laudatory writings, German physicist Albert Einstein captured the imaginations of millions after his discoveries transformed the field of physics. Hailed as a god, saint, a miracle, and even a canonized angel by his biographers and contemporaries alike, Einstein seems a figure worthy of his larger than life status. Not so fast says today’s guest, Dr. Alberto Martínez. We go deep into the personal life of Einstein, discussing his damaged relationships, intellectually incoherent views on pacifism and religion, and his own eccentric worldview.

Guest Dr. Martínez of the University of Texas at Austin joins us today to discuss who Einstein really was, and how science really is done – reminding us that Einstein was not Jesus Christ, not Harry Potter, but just a normal man.

Guests

Alberto A. MartínezProfessor of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Alberto A. MartínezProfessor of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Augusta Dell’OmoDoctoral Candidate, Department of History, The University of Texas at Austin

Hi everyone. My name is Augusta Dell’Omo. I’m here hosting an episode of 15 Minute History today with Dr. Alberto Martinez, who is a professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Martinez studies the history of science and mathematics, historical myths in science and the subject of today’s podcast, Einstein. He’s written several excellent books about Einstein for those wanting to go further, including two called Science Secrets: The Truth about Darwin’s Finches, Einstein’s wife and Other Myths and Kinematics: The Last Origins of Einstein’s Relativity. He’s now writing a novel based on Einstein’s life. Dr. Martinez, thank you for being here.

Thank you. I’m glad to be here.

So I want to start off with I understand that you’re writing a novel about Einstein so why did you choose fiction to tell his story?

Well biographers have been using fiction for decades, for a long time. They just don’t say it. So every time they write sentences that say things such as “Einstein may have, or he would have he probably this he must have done this or that.” They’re essentially filling in the blanks stories about how Einstein maybe he had autism, or that e=mc2 led to the atomic bomb, or that his wife was a secret coworker that he was inspired by patents or clocks in the Swiss culture to discover the relativity of time. It’s all fiction. Demonstrably. Einstein lived it, he complained about it. This guy is suffering that there’s this myth making -process going on as he lives: he says the newspapers lie about him biographers then repeat it. So in 1949, for example, he said, “they’ve already been published by the buckets full such brazen lies and other fictions about me that I would have long since gone to my grave had I let myself pay any attention to it.” So my book recognizes that this is true. And it becomes a comedy, the absurdity that he knows there’s something crazy. This is kind of a mass psychosis going on around him.

And it also connects to the more personal complaint that he had towards his biographies. He says that what they’re missing is the irrational. And he mentions it in a preface to a biography that was written by one of his two stepsons-in-law. He says, “what has been overlooked is the irrational, the inconsistent, the droll, even the insane which nature constantly implanted in an individual for home amusement. These things are singled out only in the crucible of one’s mine.”

That’s so fascinating, especially because everything that I’ve previously seen and heard about Einstein does really put him up as this saint-like figure so how would you like us to see him?

Well, he doesn’t think he’s a saint. And I agree. He’s often portrayed as this bleeding hearts suffer for all humanity, loved by everyone. And in fact, during his life, Einstein is unpopular with many people. Many times he opens his mouth says the wrong thing and he upsets people. But this recurring habit of portraying him in this religious light is something that really, really, irks me, for example, the latest number one New York Times bestselling biography by Walter Isaacson Einstein it describes in the following words and just the first few pages: it says we read these words, tidings, Halo, brilliance, genius, faith, testament, genius again, miraculous, miracle, glory, reverential, faith, God, called genius again, canonized, secular saint, Halo again, genius, or a priest-like glories inspiring brilliance, guardian, angel, reverence, usher in the modern age – it’s absurd that in order to tell a story about a scientists, an eccentric scientists were talking about him in such religious terms.

It’s medieval and he complains that this is an effect of mass psychology the same way that it’s affecting hordes of people at docs and reporters, and you know auditoriums, it’s affecting biographers and historians. He says, “Why did popular fans seize upon me, a scientist, working on abstract things. It’s one of those manifestations of mass psychology that are beyond me. I think it’s terrible. I suffer more than anyone can imagine.” He says the difference between the reality of what he has done and the popular assessment is simply grotesque. He says it’s unfair, it’s a bad taste to attribute superhuman powers to this one person in you know, basically him and then biographers, of course, walk in and say, Oh, well, that’s just Einstein. He’s such a genius. He’s just being modest what I’m trying to do in my new book in my would be- novel is you know what if he’s right? What if we take him at his at his word that there is this mass psychosis going on? I mean look at the guy before he’s famous the young Einstein he’s an underachiever, high school dropout. He fails is a college entrance exam, goes back to school, gets a college degree in teaching physics and math, you know, lowest passing grade, doesn’t get the job of being an assistant. So he doesn’t really become a graduate student. He’s not admitted into a PhD program. He’s rejected by the Swiss military service because he’s got varicose veins and sweaty flat feet, lives alone in poverty while his father’s business is collapsing in Italy. He becomes then the lowest paid employee at the Swiss pan office in Bern, where he’s a compulsive chain smoker. coffee drinker, gets his girlfriend pregnant. Then he becomes a deadbeat dad. I mean, this is all a staple of a normal life. This is a gruesome, unfortunate, ordinary, normal life. He never visit his girlfriend while she’s pregnant. Never visit the baby girl when she’s born, then she disappears from historical record. And in his spare time, this government employee, Einstein’s working on physics as an amateur, he called himself a heretic with physicists nowadays, might call a crank, a crackpot. Somehow, that lowest rank employee, this government bureaucrat in a cheap suit revolutionized physics. It’s a good story. We don’t need to make him to be some sort of a Superman.

Right, right. I love all that personal detail. And I’m so excited that we’re going to go into that further today, but just a little bit more in your novel, what are you hoping to call it?

My working title is “A Man Can Do What He Wants.”

Yeah. And so this idea of “a man can do what he wants.” We’ve talked about it a little bit. Let’s start with talking about his relationships with women and his children.

Well, that idea of a man being able to do what he wants does connect to those personal relationships he’s he has a tendency, a propensity, for doing whatever he wants speaking his mind that if he likes someone, he’ll try to do something about it. If he doesn’t want to see someone, he’ll try to ignore that person. And of course, this is very, very painful to the people around him. There’s something selfish, but self-empowering. He wants to be himself every day, every hour, his whole life. And he has gotten encouragement for this from a philosopher. “A man can do what he wants, but he cannot want what he wants.” That is, you cannot choose it. If he likes a woman, then he likes her, you know, he still try to go with it, even if he’s a married man. So he’s charming, but he’s a sexist guy. And as I mentioned, he’s a deadbeat dad, after the issue with the missing daughter than he has similar problems with his two sons that he subsequently has, with his first wife. Pretty awful relationships with both of them. One of them eventually goes crazy. His son Edward, and Einstein routinely neglects him, abandons him, causes the young man an enormous amount of stress. He blames his wife for the problems his son is having so well these you know going insane, it’s a genetic instability that he inherited from his mom. So he goes from thinking that this woman that he originally met in college, he used to study with and he saw it as his equal, he comes from thinking that she’s a wonderful person that is intellectual equal the thinking, eventually that she is just a stranger she’s genetically effective she’s unfriendly, she’s a humorless creature who gets nothing out of life, he writes and extinguishes the joy in everybody else’s life.

It’s, it’s astonishing. How does he empower himself to be so rude to her? So he’s hurting these people around him. And when he can’t take it anymore, he says, Well, look, I’ve got a job in Berlin, I want to leave in Berlin, I want you to live in Switzerland, you know he manages to push her away push them away and what they don’t quite know is that in the meantime, he’s been having an affair with his cousin, his first cousin who lives in Berlin. So he moves in with his first cousin Elsa, and you know the affairs been going on for years. He says, I’ve gotta love someone, I love you – promises her that he’s going to divorce his first wife, Mileva and she’s begging him year after year, please, you know, divorce this woman, I need you to marry me. And meanwhile, she’s got these two daughters. He’s hanging out with the three of them. And eventually, strangest thing happens. He gets a crush on one of the two daughters by the time this is clear in correspondence, she’s about twenty and he’s about thirty-nine so we know this happened because at the moment the daughter Ilse is so strained them and shocked by the she writes a letter desperately to a friend asking for advice and the top letter she’s cross – this really happened – she writes, “please destroy this letter immediately after reading it.” But the friend didn’t destroy it. So we know.

So this is the context, this is the daily life is this is a guy who’s relatively impulsive, relatively reckless and as he’s choosing to try to be with whomever he wants, he’s hurting a lot of people. Now what do biographers normally do? They say, well, they look at a letter like this one in which Ilse is desperately confessing what’s going on. She says, well, the other night this thing happen in which suddenly a question that was brought up in jest whether Einstein wanted to marry me or mom suddenly it was a topic of great deliberation that had to be analyzed in great detail. And Einstein said, he’s willing to marry either one of us. So a biographer looks at that letter and what they they’re prone to say what they actually say in writing some of them as well, “this is probably a half true fantasy written by a young woman as a ploy to manipulate someone a psychological game she’s playing.” Look, this is phenomenal. This is the good stuff. So the format for novels, you got to take that stuff, which is the interesting stuff, you got to run with it after all, you know, we got to relieve some of these sources.

Right. And so when you’re looking when you’re constructing this novel and you’re talking about you have on one side this this fixation, you know, this kind of impulsive nature with some of his personal relationships. And then you have what you’ve seen in biographers, this lauding of his science and everything being subscribed to him, what are you seeing is the importance of his contributions to science? And what does he think about his science?

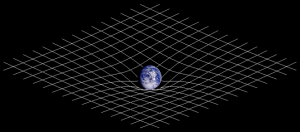

Well, good point, he would have appreciated your question because he thinks that other stuff is just merely personal, private stuff that we should really not get into because what matters about a man of his type is, you know, what he actually thinks and writes. So I can’t personally appraise all of Einstein’s contributions briefly. But among the best things he did, he showed that light behaves as if it’s made of particles when it is immediate or absorbed from matter. He explained the behavior of pollen in in water as the caused by the motions of the invisible atoms and molecules that constitute the water, several other things. But to me the greatest works were his theories of relativity. He showed that light is affected by gravity. He showed, strictly speaking, Newton’s physics was defective which is epic in its own right. It’s a phenomenal thing to have this physics dominate over the minds of people for two or three centuries and have someone this kind of low level patent guy come along as an amateur physicist and show that Newton is is wrong is a wonderful story. So Newton had assumed that forces can propagate infinitely quickly or that objects can be perfectly rigid or that we can all agree about our notions or measurements of time or sequence in time. Einstein undoes all that but how does he think about all this – that is different?

Einstein thinks that any interpretation of his contributions, there is indeed this mass psychosis going on. He thinks it’s paradoxical that he says, nobody understands me. But everybody likes me. Like, people love him. But they’re somehow mystified, they can’t understand what he’s so he’s so he says, “It has been my fate that my accomplishments have been overvalued, beyond all bounds for incomprehensible reasons.” He doesn’t see his so-called discoveries as permanent contributions to science. He thinks they might go – he in fact write an essay in 1919 in which he are used the truth of a theory can never be proven. So he really is adamant about the notion that the basic elements the principles of physics in general, and the principles of his theories, are free creations of the human mind. That’s how he sees them. He says they are inventions, not discoveries. A striking example of this happened after he had created the theory of gravity in 1919 become world famous when it’s confirmed in 1919, I mean, he created in 1915 published in 1916. Complicated series of equations that require exact solutions. If you’re going to apply this to specific problems, you’ve got to actually work with these equations to find the approximations One physicists Cornelius Langrasse to do this. And he goes up to Einstein explains to him, look I’ve been trying to find certain approximations, I’m making some progress. Einstein looks at him surprised and says, “but why would anybody be interested in getting exact solutions to such an ephemeral set of equations?”. And the guy shocked – Langrasse is shocked, completely shocked. But he says, “this is a marvelous example of the degree to which Einstein has a complete lack of dogmatism.” And I argue that it’s that lack of dogmatism that empowers him to actually do what he wants which is, you know, change some of the principles of physics

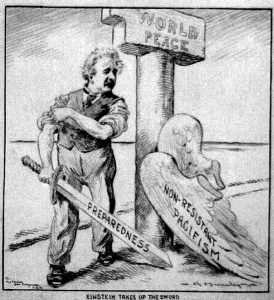

So when we get into this lack of dogmatism, and really Einstein says propensity to do what he wants, I want to talk about some of the conceptions or perhaps misconceptions that people have about Einstein. So was Einstein a pacifist?

Sort of have since childhood, he hates militarism. He hates uniforms, rifles, he doesn’t want to be a soldier doesn’t want to kill anybody. But at the same time, he’s grossly inconsistent throughout his life. So for example, in World War I, he signs a pacifist manifesto that, you know, nearly nobody signed and garnered no attention. But at the same time, there’s this guy following Einstein around sensing that Einstein is potentially you know, a great thinker, let me interview him. And he asked Einstein, do you worry that the there might be applications of your scientific discoveries that might have negative consequences? Einstein says, No, not at all. So long as I’m working on something, and it’s an interesting puzzle to me. The applications are completely indifferent to him. So the guy gets really creeped out. And sure enough, during the war, World War I, suddenly Einstein’s designing airplane wings, the pacifist, for an aircraft company in Berlin, Johannisthal, a company that made airplanes for the German Air Force so he’s also designing gyro-compasses for ships basically for the company of Herman Anschütz who’s the guy who’s made gyro compasses for the German Imperial Navy. So again, you need compasses in battle that will continue working when say other means of orientation, say magnetic compasses, are not working. You need compasses for warships, for submarines, for U-boats in 1919 designing gyro-compasses to withstand shock jolts to a ship. This is precisely the kind of illustration of someone who even though he’s kind of aloof to the war, and considers himself a pacifist. The same time is in some, you know, distance far away office contributing.

In 1933, after Hitler comes to power. Einstein says I think you know, if I were a Belgian I would happily enlist for the army and I think the Belgian should just become soldiers and fight. Pacifists get really pissed off that this guy is saying this kind of thing and say we thought you were a pacifist, calling for people to run up to arms so he’s annoying them. Like I said he’s annoying people while he’s alive by the things. It’s easier to think that he’s a pacifist when we’re no longer seen his declarations in newspapers. One of Einstein’s biographers Ronald Clark got in a bit of trouble because he said in his book that Einstein’s pacifism was like “a garment that can be tucked away in a drawer once in a while to go to war with Germany or for this or that and then you pull it out of the drawer, to be worn on a fine day, when there is no when there is no war.” This same thing happens of course during World War II, of course he signs the letter to get Roosevelt to start working on the bomb, thinking about the atomic bomb. But at the same time eventually he’s working as a consultant for the US military on designing torpedo so that they can explode the hulls of shapes and submarines. Not the typical thing that pacifists do.

Right so now that we have all of this – how would you see Einstein’s worldview?

The main thing in Einstein’s worldview is that he thinks everything in nature is cause and effect that is he believes him determinism. There’s no randomness, there are no miracles, what happens, happens and it can’t be avoided. If he wants something he wanted because there are causes that he can’t that he can’t avoid. He recognizes that humans have social aspects and solitary aspects and he’s this example someone who is constantly yearning to be alone so he can have some quiet time to think about things but at the same time he’s constantly accepting invitations to be social. Hobnobs with people, but has a bit of phobia towards people in general. He dislikes people who he says don’t have an intellectual life. He hates that some people live for material things. People who think that the height of existence, the best things in life are fish eggs and champagne oysters and wine. Hates them

He’s a guy who doesn’t like technology – doesn’t trust that it will necessarily make our lives better. He thinks many people are moved by fear and stupidity: he sees that happening in World War I and World War II and makes comments about that. But he has I mean, he has a whole book titled, you know, My View of the World so so one could go endlessly on about these things. But I think you know, going back to my initial reaction – he’s he’s fascinated by the pursuit of the truth, seeking the truth, and rising above the merely personal details of one’s life. But in that process, he doesn’t think things are happening randomly. He thinks everything has a cause and if we apply ourselves scientifically, we can figure it out. For example, there’s no free will. If he does anything. If Hitler does anything, it’s because they had no choice but to do it.

And so when we’re thinking about Einstein ideas about cause and effect ,freewill, how does that factor into what you’re seeing, as was Einstein a religious person?

He says he is. I don’t believe it. I think it’s absurd. I think it’s one of his politically correct lies. I would say that he is vigorously non-religious. But here’s a guy who as a kid is very religious. He believes in Christianity and Judaism. simultaneously. He writes little songs to God and sings them on his way back from school, but by the time he’s a teenager, he read some science books and becomes convinced some stories in the Bible cannot possibly be true. So he gives it all up. He shakes it all off and becomes this kind of, you know, crazy free thinker. By the time he becomes famous, everybody becomes fascinated by Well, what? What does the wise man think about God? When you think about religion? The afterlife? Hordes of people ask him such questions. priests, rabbis, reporters, heads of state, fans, little girls writing postcards, acquaintances, and his answers change over time. They’re very erratic. He’s very inconsistent and irrational, as he said.

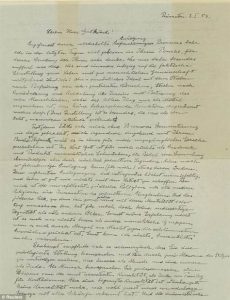

So if you look at the answers, there’s an Einstein for everyone. There is if you’re an atheist, there’s an Einstein for you. If you’re Christian, there’s an Einstein for you. If you’re Jewish, there’s an Einstein for you. If you’re a pantheist, here’s an Einstein for you. So naturally, this works. This is what I mean by politically correct, he’ll say things to get along. So by the 1920s when he’s suffering the first wave of fame of being assailed by thousands of people he seems to have switched towards a pantheistic view whereby God is nature and we can kind of witness the greatness of God and everything around us. So say in 1927, he’s at a dinner, where he mentioned that he has a veneration for a force that is subtle and intangible and inexplicable. The same year, he says that there is this infinitely superior spirit, a reasoning power in the universe. Now, this is all very reassuring for anybody who wants to have Einstein on his side. The problem is that every now and then, when people try to pin him on something he’s actually said, whether it’s in a conversation or, in an offhand remark, sometimes, he backtracks, and he says, Well, when I said, “God,” I didn’t really mean “God.” I meant something else. So at one point, for example, he says, well, “the dear lord is subtle, but he’s not malicious.” People are fascinated. They said, “I see Professor Einstein what you’ve said the other day. Would it be okay if we etch it on the fireplace at Fine Hall at Princeton?”

And you know, he replies: “sure you know you could put that on the fireplace but you know what I what I meant when I said the dear lord is crafty but not malicious. What I meant is nature hides it’s secrets through the sublimity of its essence, but not through trickery.” So you see, it’s almost like he takes it back. So is he is he religious? You asked me, my answer is no. And the reason is, he doesn’t believe in prayer. He doesn’t believe in wishful thinking. He says, if you pray, you’re not religious. He doesn’t believe in any holy books, doesn’t accept the Bible doesn’t believe in Revelations, miracles, he says – “there are no miracles ever. There’s no morality given from God.” He believes in no savior, no life after death, no reward, no punishment, no goal, no goal in nature. He thinks – it’s not going this existence we have, it’s not going towards anything. So he calls himself deeply religious again and again, but I think it’s because he has redefined what it is to be religious, so that it is precisely whatever he is. If he believes him cause and effect, then that’s one of the most religious aspects we could ever have. If he believes that we should have a sense of wonder at the grandeur of the world, that’s a very important central religious feeling. If he believes that prayer is something that we should not do, then the most religious people do not pray. He says, the most religious people have no need pray. See this is disingenuous. It’s absurd. Some friends call him out on it. By late in life in letters, he’s openly not admitting to a few people, in letters, saying I’m agnostic, you know that he doesn’t know if God exists or if God doesn’t exist. And recently, a letter that have been discovered just years ago was, was resold for nearly $3 million dollars, a letter in which he makes his most disparaging comments having to religion in 1954, he writes: to me, the word God is nothing more than the expression of human weakness in the Bible is a collection of honorable, but still primitive, legends abundantly.” So you can see again, he’s an eccentric guy. He’s an unusual guy, but he’s politically correct enough to try to be sensitive whenever he’s saying things in public so that he’s not really ruffling feathers.

So to conclude, what’s the big picture? Why does all this matter for understanding of Einstein?

Well, I think it matters because so long as we keep portraying Einstein as a saint, we just don’t understand how physics is done. It’s not done by miracle men. It’s not that he was born different. He’s not Jesus Christ. He’s not Harry Potter. He was not marked since birth. He’s a normal guy – you can see it if you look at his youth. He has a lot of defects, a lot of failures. So basically teaches us that what one fool can do, another can.

Thank you so much, Dr. Martinez, for being here. This has been another great episode of 15 minute history.

Thank you Augusta, my pleasure.