This episode looks at US perceptions of Mexico through map making during the US / Mexico War, in which a private publisher sold maps that were reissued annually to reflect ongoing progress in the campaign. Intended for a general, popular audience, these maps served as propaganda in aid of the conflict, but historians and military analysts alike have ignored them until recently—even though they may well have influenced the positioning of the border at the war’s end.

Guest Chloe Ireton looks at the intriguing history of maps as propaganda and the role of two publishing houses—J. Disturnell and Ensigns & Thayer—not only in rewriting the history of the Mexican-American war, but in influencing the outcome of the war even as it was still ongoing.

Guests

Chloe IretonLecturer, University College, London

Chloe IretonLecturer, University College, London

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Specifically, I am going to talk about maps of Mexico produced by two US publishing houses based in New York: J. Disturnell and Ensigns and Thayer, which each organization revised and republished on numerous occasions during the war years.

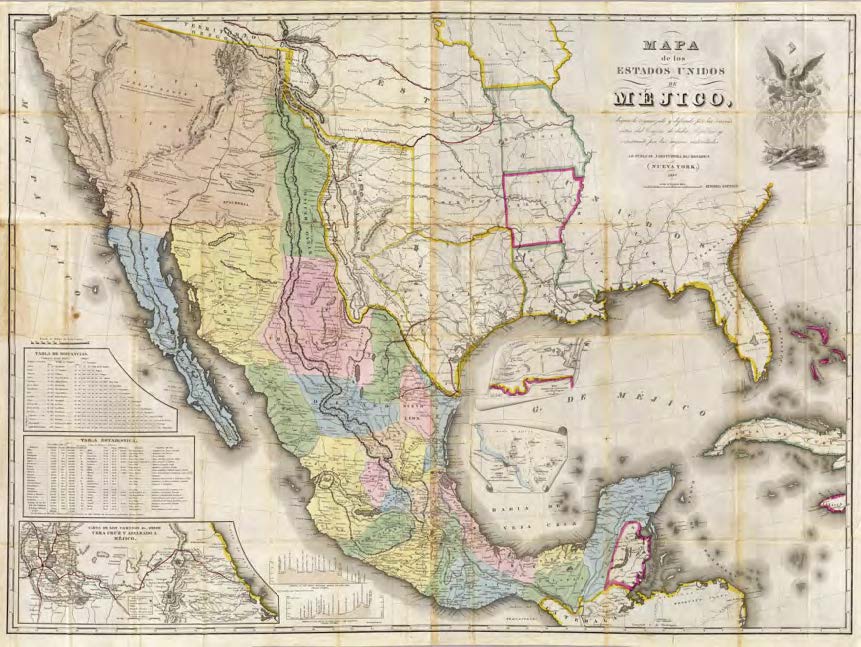

J. Disturnell was one of the most prolific map publishers in the US during the mid nineteenth century. The publisher focused mostly on tourist guides and maps of North American states and regions. Disturnell published at least three separate maps of Mexico between 1846 and 1848, each of which he revised and republished almost annually during and in the aftermath of the war years.

A defining feature of Disturnell’s Mexico maps was that he copied the cartography from older map publications, but added annotations and inserted other notes and sketches, which served to visually represented North American gains during the war. This process of adding details as they happened and republishing, illustrated the new literal and figurative definitions of the American nation almost in real time to his audience.?¹

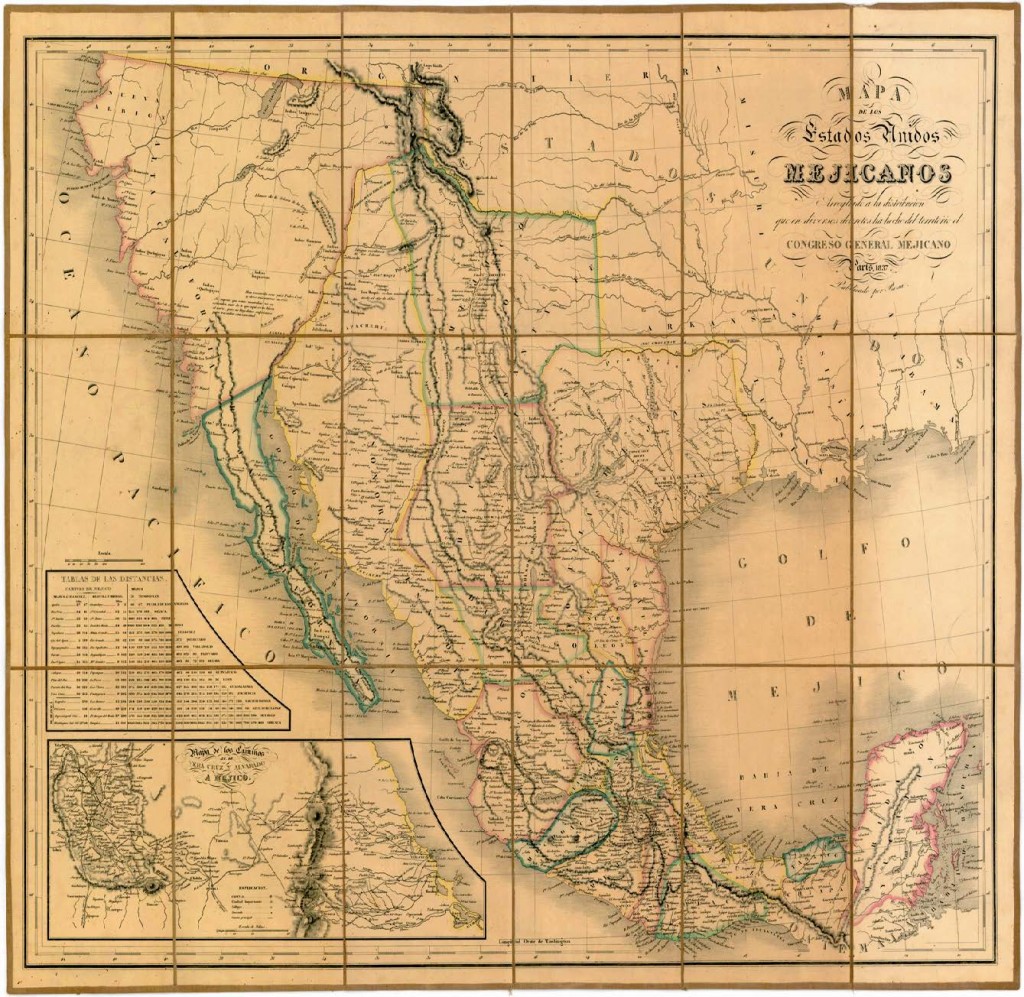

In 1847 Disturnell published the Mapa de los Estados Unidos de Mejico, Segun lo organizado y definido por varias actas de Congreso de dicha Republica: y construida por las mejores autoridades.?² It was a copy of a map printed a decade earlier in Paris called Congreso General Mejicano. Mapa de los Estados Unidos Mejicanos, 1837. Disturnell’s map is bilingual, retaining the Spanish title and therefore also the ironic notion that the Mexican Republican Congress had approved the contents of his map. In fact, his map was a copy of a map that was twenty years out of date.?³ The English part of the map on the most part represents Disturnell’s descriptive insertions of the geography and history of Mexico and recent events, while the Spanish text represents the areas of the map that he directly copied from the Paris edition.

What is distinctive about the Disturnell Maps?

Disturnell inserted key symbology into his 1847 map and the 1850 revised edition of the map in order to strengthen a sense of US national identity. The most obvious purpose of Disturnell’s maps was to redraw the boundaries of the US nation. When comparing Disturnell’s 1847 map and the original 1837 version that he copied, it is clear that Disturnell altered the border.

In the 1837 version, Texas was represented as part of Mexico and therefore not independent, even though Texas had declared itself a republic in 1836. In the 1847 copy, Disturnell altered this, portraying Texas as independent from Mexico. As a result, Disturnell changed the US-Mexican national boundary too; clearly drawing the border between the two nations as running across the Rio Grande.

It is important to remember that this was an anticipatory move – in 1847 neither side had reached a formal agreement about the border. It was not until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 that both sides finally agreed that the course of the Rio Grande would define the new national boundaries.?4

Aware of the fact that the border had not yet been formally agreed, Disturnell inserted the text, Boundary As Claimed by the United States. In spite of this text, his portrayal of the “new” border would have made the contentious border a reality in the minds of viewers of the map, since the border is clearly drawn at the Rio Grande.

As an example of the power of maps and the boundaries that they portray, in a fundamental study on the politics involved in mapping the US-Mexico border after the war, Paula Rebert, has illustrated how the political negotiators in both nations during the 1848 border treaty negotiations mistakenly used the seventh edition of Disturnell’s highly inaccurate 1847 map.?5 Rebert argued that this caused severe conflicts between the cartographers from both nations, as the cartographical representations did not reflect the geographical realities on the ground, thereby causing difficulties in plotting the new border.

When taking into account the power of visual representations, it is worth asking whether Disturnell’s anticipatory drawing of the new border, which in effect made a reality of something that had not yet been realized in a treaty, affected the political choice of where the border would run when politicians did actually negotiate the treaty. Such questions tend to lend to historical speculation, as it is impossible to discern the precise effect that Disturnell’s map may or may not have had during the negotiations of the Treaty.

So you spoke of how Disturnell’s maps created a new sense of national identity, except for redrawing the boundary what else did he change?

One of the salient features of both Disturnell’s 1847 and 1850 editions was the pressing need to create a revised national sense of identity that takes into account impending extended geographical boundaries. Both editions feature heavy annotations of the new territories. In 1847 Disturnell noted that these regions were “as claimed by the United States.” Reflecting current events, the 1850 map represents the Hidalgo treaty of 1848 and California is clearly outlined as a US territory. In the 1847 edition, Disturnell mapped a California that Mexicans had failed to properly inhabit and put to productive use. There are ample descriptions of how Native Americans dominated the territories and of independent Indian tribes that both the Mexicans and their Spanish predecessors had continuously failed to assimilate into the Mexican nation.

In contrast, the textual inserts in California in the 1850 edition, present a bountiful ex-Mexico with vast natural resources that would be beneficial for the US. For example, whereas in 1847 edition Salt Lake just appeared as a name, in the 1850 edition Disturnell inserted a text describing how important the region was: “the Salt Lake is one of the wonders of nature, and perhaps without a rival in the world, is a saturated solution of salt, of an hundred miles of diameter”. In another part of California Disturnell inserted, “The bear river valley with its rich bottom, fine grass, fields of blue flax, hot mined springs, volcanic rocks, saline efflorescent is also a rich and interesting region.”

What do these differences tell us? The differences between the two editions illustrates that in 1847 Disturnell was creating a narrative of Mexican failure to inhabit the lands and control the Indian tribes in the region. Through the descriptions in the 1850 edition of the vast resources that the US had discovered, Disturnell was implicitly suggesting that the US had a rightful claim to these regions because Mexico had failed to inhabit the lands, integrate indiand within the nation state, and most importantly establish any productive industry in the area.

Are these themes of Mexico’s failure and the US’s right to the new lands present in other maps of the period too, or are the Disturnell maps unique in this regard?

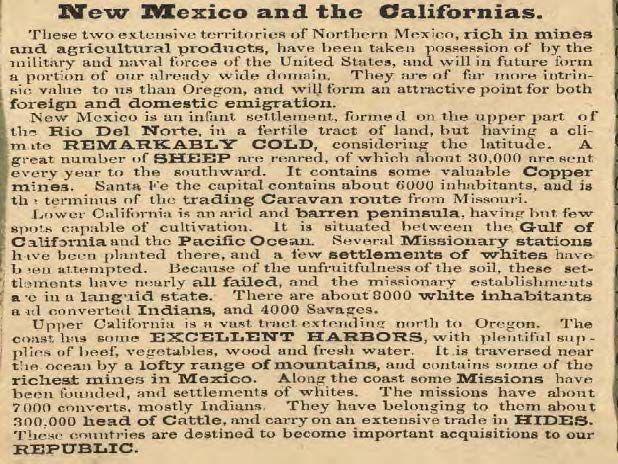

Absolutely, there are certainly other examples. For example, An Ornamental Map of the United States and Mexico, designed by W. Phelps and published by Ensigns and Thayer also presents similar narratives on the new territories. The map was revised at least once, since there are two surviving copies from 1846 and 1847. Like the Disturnell map, the Ornamental series are visual representations of the new and extended nation rather than accurate representations of the geography. The Ornamental map is more visually descriptive, since the actual cartographic representations take up approximately half of the total image.

Therefore, while Disturnell’s maps could have been confused for a scientific and accurate representation of cartography, these Ornamental Wall Maps served a clearer purpose of illustrating key aspects of US geography and history to a US audience. In spite of the immediate visual differences between Disturnell’s and Ensigns and Thayer’s maps, both represent similar national narratives to Disturnell’s descriptions of California in 1850.

The insets in the Ornamental Map continue the narrative of presenting Mexico as a failed state and show US possession of the new territories before both nations had reached any agreements. An inset describing the new territories describes New Mexico and California’s natural resources and viability for economic development within the US nation. The last line in the description of New Mexico and California reads “These countries are destined to become important acquisitions to our REPUBLIC.” Therefore, Ensigns and Thayer, like Disturnell, were also defining new American territories in 1846 and 1847, prior to it being a reality.

Other insets describing Mexican history, also serve to justify such acquisitions by the US, by representing Mexico as a failed state. The insets on Mexican history, feature an in depth description of the wonders of the Aztecs and Montezuma, with no description whatsoever of present day Mexico except to say that the Mexicans have not preserved these historical treasures. In this narrative, Mexico had therefore destroyed the legacy of a great civilization, and failed to become a functioning nation state, since there was nothing worthy of describing in the present day country. As such, this map presents Mexico as a defunct empire, thereby justifying US colonialism of it.

The representation of Mexico as a failed state is further justified through the presentation of statistical data. These statistical tables are really striking and would make great teaching resources. By using different sets of data to compare the two nations, Ensigns and Thayer represented Mexico as having the potential to be economically productive because of its natural resources, but instead being highly financially indebted because of the country’s inability to establish productive industries. This statistical visual representation therefore served to justify US supremacy.

For example, the US table lists the “Amount of Continental Money Issued,” at $358,000,000, whereas for Mexico the table provides information about the level of public debt, $16,000,000 and the revenue from the mining industries, $20,000,000. The details of the revenue from US industries however, were not provided. Instead, these mapmakers carefully tailored the statistics to make the US look far more prosperous and dominant, while portraying Mexico as a desirable place for US investment and colonial expansion, especially since it was so incapable of managing its own financial affairs.

The data also served to represent Mexico as inferior, in terms of progress. For example the supposed number of Indians in the United States is completely insignificant, 744,685 in contrast 17,063,355 total population, whereas in Mexico almost fifty percent of Mexico’s ‘meagre’ population of 8,000,000 were supposedly Native Americans. The two timelines of events presented in the table are also indicative of these narratives. The historical timeline of the US represents events such as:

- First Colonial Congress

- First Union Convention

- Constitution Adopted

- Peace Concluded

- Mexico Invaded

In contrast, the representation of Mexican history is marred with struggles to establish a nation. Key events described include:

- Iturbide, a military chief declared Emperor

- Divided into 14 States, 3 territories and one district

- State Legislature Abolished

- Santa Ana Declared Dictator

- Texas and Other States Rebel.

These competing visualization of history, the choice of the events described and the language utilized all represented clear US superiority as a nation that had successfully fought wars and emerged as a progressive nation with a rule of law. In contrast, the data illustrated Mexico as ripe for conquest. According to the timeline, Mexico had been marred with political upheavals and failed attempts to establish a nation state.

Lastly, the statistics also represented Mexico as a region that had failed to shake off its Catholic colonial history. In spite of the significant anti-clerical conflicts and debates that were ongoing in Mexico at the time, the statistics table for Mexico states that the country had 10,000 priests.?6 No mention of religiosity in the US is made in the respective table.

Representing Mexican Catholicism in cartography is not unique to this map. In Disturnell’s 1850 edition of the national map of Mexico, he divided the various states by religious administration, thereby also representing an image of Mexico as fervently Catholic. These numeric and visual representations failed to illustrate the acute internal battles in Mexico over the power of the clergy, and instead drew a picture of continuity from colonial rule under the Spanish Catholics, symbolizing a clear lack of progress since Independence.

You mentioned that these maps were often republished regularly throughout the war. Do we get any sense of the ongoing war through the maps?

Yes, absolutely! Disturnell permeated textual representations of US military activities throughout the 1847 national map of Mexico. Routes that US troops established into Mexican cities and the locales where key battles took place are represented by thick red lines with texts such as, General Woods’ 1846 Route from San Antonio to Monclova. Another route called General Taylor’s route of 1846 visually represents the route from Corpus Christi Bay to Puerto Isabel, where the text informs the viewers of the battles of Palo Alto and Rosaca de la Palma in 1846 and the establishment of the US military base Fort Brown. The route then continues south of the Rio Grande to Mier and then South West through Monterrey to Saltillo.

Disturnell does not provide information regarding the subsequent battles that took place in those towns, nor whether the troops were still there when the map was published. The information simply represented that the Generals had established the routes. Through the marking of these routes, Disturnell was informing a US audience of the most recent events in the war.

In the same year J. Disturnell published a map called 1847 called Pocket Map: A Seat of War in Mexico, Being a copy of General Arista’s Map, taken at Resaca de la Palma, with additions and Corrections; Embellished with Diagrams of the Battles of 8th & 9th May and Capture of Monterrey with a memorandum of forces engaged results &c,. and Plan of Vera Cruz and Castle of San Juan de Ulua. The Disturnell Seat of War map illustrates the most recent events in the War in almost “real-time.” The map was a copy of a Mexican map that General Taylor discovered among the possessions of General Bautista after the US victory at Resaca de la Palma in 1846.

This discovery had been of huge military importance to the Americans since the map illustrated accurate routes in northern Mexico. Previously US generals had relied on highly inaccurate maps that did not have detailed information about the terrains to the south of the Rio Grande. Military historians have argued that this map was of key importance in the decisive victories along the route to Saltillo.?7 General Taylor appropriated the map in the battle of 1846 and by 1847 Disturnell had copied and printed his version of it.

The red routes in the Seat of War map are far more extensive than those represented in Disturnell’s 1847 national map. Therefore, if these maps are taken at face value, in one year alone the extent of US penetration into Mexico had almost doubled. Disturnell also inserted red flags to represent towns taken by Americans – a feature that was not present in his previous 1847 map. These changes illustrate why the New York map printers revised the editions and republished maps so frequently. The fact that the same publisher printed two maps in the same year that represented such different visions, suggests that maps were in fact a means of visually representing current events in real time to a North American audience.

The last significant mode of representing recent events that Disturnell employed was the inclusion of insets depicting the major battlefields. The 1847 national map had two insets, while the 1850 had five and the 1847 Seat of War map had six. These map insets are key additions to the map as they illustrate the extent of US military penetration deep into Mexican territory. Most often, these insets represented events that had occurred less than a year before the publication of the map.

These images depicted US victories and clear military superiority and continued the narrative of Mexico as a failed state. An inset that is present in all of the maps is a sketch drawn by J. H. Eaton 3rd that represented the US victories in Palo Alto de la Cruz and Besala de la Palma along the Rio Grande on the 8th and 9th of May 1846.

The second inset in the 1847 map, is a sketch of the Gulf of Mexico drawn by Admiral V. Admiral Baudin. It represents the bay of Veracruz and the roads from Veracruz city. The map shows key US losses, such as the sinking of the Brigg Sommers boat in crossfire in the bay on Dec 13th 1846.

In the 1850 edition of the national map, Disturnell featured a diagram of the battleground on February 22nd and 23rd of 1847 in Saltillo explicitly showing the positioning of US and Mexican troops. Another inset in the 1850 map of Monterrey and its environs clearly illustrates that Mexicans were defending a very small fraction of the town when the US took possession of it. When you look at the inset, the position of the Mexicans is illustrated through shading, thereby making it clear to the viewer that the Mexicans had little power.

Disturnell’s Seat of War map includes further references to US victorious imagery. In a textual insert Disturnell described how, although vastly outnumbered by their Mexican enemies in every single battle, the US still won and had relatively few casualties. The Mexicans on the other hand always suffered vast losses. Such textual representations are complemented by an inset image inserted West of Mexico of a US soldier on a horse carrying a large American flag who is devastating Mexican soldiers with his superior force. In the image, two Mexicans lay slain on the ground by the horse’s feet. Such imagery would have served to evoke national pride and assert an imagery of US dominance over Mexico.

These varied visual depiction of US victories and the lack of any representation of US losses would have implied to a US audience that the Mexicans did not seriously resist or defend their nation. Therefore, the insets continued the narrative of Mexico as a defunct and failed nation state that were implicit in the symbolism of the textual inserts and insets in other parts of Disturnell’s national maps and the Ornamental Wall maps.

So how would you sum up these US maps?

The American maps published during the war years often represented a direct need to visualize the rapidly changing geography of the American nation and explain the victories of the war, as well as justify the need for the war. Imagery illustrated the prowess of the US military as well as the many victories.

The representation of Mexico served as a means of describing the “Other” in order to self-define as a nation. Comparing US natural resources, economy, population, and other key factors to those of Mexico by using different types of data and imagery meant that cartographers were able to represent the US as the dominant neighbor and the rightful claimant on Mexican land, on the basis of need and potential usage.

The US maps discussed were most probably published to educate a US audience of recent events in the US-Mexico war. In representing such events, the cartographers and publishers presented a US national narrative that defined itself in contrast to its southern neighbor. Mexico was represented throughout the narratives in the maps as a failed nation that had not yet shaken off its colonial history, was marred by political conflicts, controlled by Catholics and had failed to utilize its natural resources productively. The conquest of the northern Mexican territories was therefore justified through a narrative of Mexican failure to fully utilize them.

Repeated publications of the same maps with new additions representing the most recent events illustrated an active desire in the publishing houses to describe the recent events and incorporate them into the US national historical narratives that the maps already presented.

Notes:

- Paula Rebert, La Gran Línea: mapping the United States-Mexico boundary, 1849-1857, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001).

- J. Disturnell, Mapa de los Estados Unidos de Mejico, Segun lo organizado y definido por varias actas de Congreso de dicha Republica: y construida por las mejores autoridades. (Lo Publican J. Distunerll, 102 Broadways, Nueva York, 1847).

- Paula Rebert discussed the inaccuracies in: Rebert 2001 (see #1).

- Timothy J. Henderson, A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States, (Hill and Wang, 2008).

- Rebert 2001 (see #1).

- Alan Knight, “Peasants into Patriots: Thoughts on the Making of the Mexican Nation,” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos10, No. 1 (1994): 135-161.

- Jack Jackson, “General Taylor’s “Astonishing” Map of Northeastern Mexico,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Oct., 1997), pp. 143-173.