In this episode, we tackle “that pesky standard” in the Texas World History course that requires students to understand the development of “radical Islamic fundamentalism and the subsequent use of terrorism by some of its adherents.” This is especially tricky for educators: how to talk about such an emotional subject without resorting to stereotypes and demonizing? What drives some to turn to violent actions in the first place?

Guest Christopher Rose from UT’s Center for Middle Eastern Studies offers a few suggestions and some background information on how to keep the phenomenon in perspective.

Guests

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

The standard I’m addressing reads as follows:

(14) History. The Student understands the development of radical Islamic fundamentalism and the subsequent use of terrorism by some of its adherents. The student is expected to:

A) Summarize the development and impact of radical Islamic fundamentalism on events in the second half of the 20th century, including Palestinian terrorism and the growth of al-Qaeda; and

B) Explain the U.S. response to terrorism from September 11, 2011, to the present.

In talking about this, I’d like to suggest three points to bear in mind:

- Keep it in perspective

- Not all extremism is Islamic

- What are the roots of discontent?

1) Keep it in Perspective

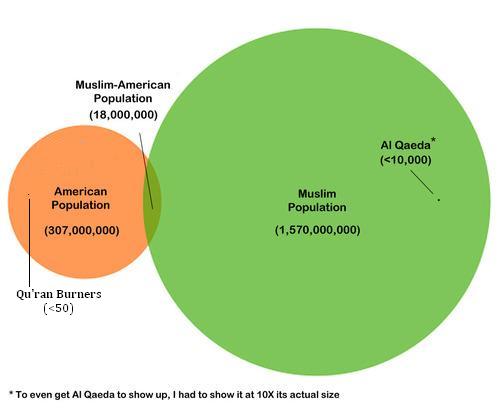

Even though it gets a lot of news, the number of people involved in extremist activities is actually quite small.

The number of people directly involved with the 9/11 plot, including the 20 hijackers, was less than 50. At its most powerful in 2003, all of the al Qaeda branches together had less than 5,000 active members, this out of a worldwide Muslim population of over 1.2 billion.

Megan Reid of the University of Denver put together a chart documenting the numbers of protestors who turned out in various locations against the Innocence of Muslims video, comparing it with the number of protestors who participated in the Arab Spring.

The first point I would make is, remember when talking about this subject that, although it is an important topic in current events, we are still talking about a very small percentage of the overall Islamic population of the world, and remember to bring that up. Most of the world’s Muslims don’t have anything to do with terrorism.

2) Not all extremism is Islamic

The standard mentions the “impact of radical Islamic fundamentalism … including Palestinian terrorism.” This is a problem, because until the 1980s, Palestinian terrorism was actually secular in nature, usually Marxist. The idea that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is seen as a holy war is actually an idea that’s held in the west, but only by the extremists on both sides on the ground there. Most Israelis and Palestinians simply see this as a battle over land and resources that they both claim as their own, based on historical precedent, not religion.

This chart explains who some of the active groups are, but, in a nutshell:

Right now, the West Bank is controlled by the Palestinian Authority, which is the successor to the Palestine Liberation Organization, or PLO. The PLO is a secular group that was founded in the 1960s and was associated with Yassir Arafat. Arafat, for the record, may have given lip service to Islam, but his religious devotion ended around happy hour.

Its main rival for decades was the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, which was a Marxist organization run by George Habash. The PFLP fizzled out in the 1970s, and was replaced as a key actor by Hamas, which is the Palestinian chapter of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hamas took off in the 1980s with support from Hizbollah in Lebanon, and they now control the Gaza Strip.

It does bear mentioning that there are small Jewish extremist groups at work in Israel that also fuel the conflict. Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a young right-wing Jewish man in 1995, which was a huge shock to many Israelis.

The Ba’athist movement that is the dominant political force in Syria currently — this is the ideology that is espoused by the current Asad regime — as well as espoused by Saddam Hussein in Iraq is another secular movement. It was actually a political philosophy first proposed by a Lebanese Christian, Michel ‘Aflaq, as an alternative to the Pan-Arab movement that was espoused by Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser. ‘Aflaq wanted to propose a pan-Arab ideology that used less Islamic terminology so that Arab Christians wouldn’t feel threatened or left out. It was adopted as a state ideology in both Iraq and Syria — then, of course, both countries decided they were practicing it properly and the other was doing it wrong, so the two regimes never got along.

Saddam Hussein suddenly decided to start working in Islamic symbols into his government in 1990 after the invasion of Kuwait in a misguided attempt to rally the world’s Muslim population to his side against the allied forces who were preparing to launch a military strike against him. It didn’t work–the pictures of him sharing lots of alcohol with various state leaders, rumors of many mistresses, etc, were too strong for him to be credible as a religious man. Also, many people just didn’t like him.

Al-Qaeda is an outgrowth of the Salafist movement, which claims to be seeking a return to “pure Islam” as it was practiced under the prophet Muhammad and immediately afterward. Salafist practice discards a lot of what they feel is “innovation,” or practices or theologies that were added in the centuries afterward. Salafist ideology is essentially constructed on the notion that only their (the Salafis) version of Islam is correct; everyone else is misguided and, anyone who rejects the Salafist ideology is not actually Muslim. This is why al-Qaeda had no problem attacking Muslim targets–according to their own ideology, those guys weren’t actually Muslim. And they didn’t have any problem attacking Muslim targets–Osama bin Laden was responsible for the deaths of many more Muslims than non-Muslims over his tenure as head of al-Qaeda.

3) Roots of Discontent

Finally, I just want to take a moment to talk about why extremism seems to be so popular. The ultimate problem in the Middle East is that freedom of expression is extremely limited. In 2011, Freedom House listed only one country in the entire region as politically free, and that was Israel (Israel proper, not including the West Bank and Gaza). Morocco, Kuwait, Lebanon, and Turkey were listed as “partly free” – Turkey keeps going back and forth between free and partly free – and all of the other countries were “not free.”

This, combined with a population that is growing rapidly and is increasingly younger — half of Iran’s population is under thirty, as is two thirds of Saudi Arabia’s — means that you have a young, reasonably well educated population coming into adulthood with no chance that their standard of living will match that of their parents—in most cases they will have a lower standard of living than their parents did at their age, in some cases it will even be lower than that of their grandparents. Unemployment is extremely high, college graduates frequently work in the informal economy or in manual labor (if they can find work at all), and they have absolutely no chance to register their disappointment at the ballot box. They quite literally can’t do anything to change their situation, and this breeds frustration.

For years, these extremist groups — odd as it may seem — were frequently popular with younger people just because it seemed like they were doing something to change the status quo. And we are talking about people who feel as if they can’t control their futures and that they are powerless.

The Arab Spring is a similar reaction, one that’s probably a little healthier as it has actually managed to change the system in three countries already, and Syria is, as of now, teetering. And one interesting thing to note is that, although the Muslim Brotherhood won the majority in both the Tunisian and Egyptian parliaments, and some in the west are a little concerned about this, in countries that have liberalized the political process–Jordan, Lebanon, Kuwait–the Islamist parties usually come in victorious at first, but then within a cycle or two, they lose their majority and things balance out. So, if the Egyptian military can keep its hands off of things–a big if–we’ll probably see a different picture there in a few years.