Over the past two and a half centuries, the expectations placed upon the office of the President have changed and evolved with each individual charged with holding the position. From George Washington to Barack Obama, each occupant has left his mark on the office. However, since WWII, the occupant of America’s highest office has aspired to do more and more, but seems to have accomplished less and less. Have the expectations placed upon the office actually made the position less effective? In his new book “The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office,” returning guest Jeremi Suri (UT-Austin) takes a long historical look at what has made presidents successful in the role of chief executive, and asks whether the office has evolved to take on too much responsibility to govern effectively.

Guests

Jeremi SuriProfessor, Department of History; Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs, LBJ School of Public Affairs, the University of Texas at Austin

Jeremi SuriProfessor, Department of History; Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs, LBJ School of Public Affairs, the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

I’m going to begin by quoting you at you–

–that’s a dangerous thing to do!–

–I know it is! The first sentence of your book, I have a feeling, is supposed to be a trigger – and it is! “The presidency is the most powerful office in the world, but it is set up to fail.” Strong words.

Yes! My argument in the book is that this office, the presidency as we know it, has developed over time and, as it has developed over time, it’s accomplished some extraordinary things that I’m sure we’re going to talk about. But it’s reached a point now where the responsibilities, the set of expectations, the management of the tasks surrounding the presidency have made it impossible for the president to success at doing the big things that people want the president to do. Presidents end up doing a lot of small things, and not doing a lot of big things. That’s why we don’t have a lot of effective policymaking that moves forward beyond our immediate needs and immediate crises.

I argue also that this is not unique to the American presidency, I think it’s the modern condition, Chris. All of us suffer from this, we’re all spending more and more time answering people on e-mail, responding to texts, et cetera, and getting less done. So, what we see in our own lives is what we’re seeing in the presidency magnified many times over. My book is an effort to explain historically how we’ve come to this point and perhaps how we can move beyond it.

One of the things that really struck me is that you really set up the sense that, at the beginning, as we were coming out of the period of the Articles of Confederation, which the Founding Fathers recognized had not been successful, was the degree of uncertainty–and experimentation even–that we went through because they weren’t even that certain what they wanted the chief executive to be.

Yes, this is a really important point. We tend to revere the Founding Fathers–and I revere the Founding Fathers–but we get ’em wrong. These were not dogmatic men who had all the answers. That was not the case. They often used forceful language, and they enjoyed rhetoric and argumentation, but the genius of the founders was the genius of experimentation, the genius of innovation. They knew they were inventing something that did not exist before, and they knew that they did not have the answers. I deeply respect them, especially in the creation of the modern presidency, in seeking to create something that didn’t exist and realizing that it was going to evolve over time. The Founding Fathers wanted–and needed, they recognized–an office that would bring this sprawling democracy together. They were going to a larger, more participatory society than ever before – Madison, Hamilton and others comment on this – and they needed some figure, some office that would bring the country together. But they also recognized that monarchs were corrupt and degenerate, so they wanted, in the words of some, a “democratic monarchy,” which, of course, seems like a contradiction. That’s what the office of the presidency was to be.

Now, if we went back and talked to five, six, seven of the founders, we’d get five, six, seven visions of what the office should look like, and that’s the whole point in my book – that the office has evolved over time, it’s been made by the leaders in the office and the people who elected them with each generation, and we’re doing that right now.

The first occupant of the office, you argue quite extensively, really set the tone not only for the function of the presidency, but also his role both within the government and the country. George Washington. Interesting man. Can you describe how he was able to accomplish this?

Absolutely. George Washington is a fascinating figure, and, again, a figure that we often understand but sometimes misconstrue. Washington was not all-knowing, and he was not this godly figure that’s often depicted in the Gilbert Stuart portraits that I love, actually! Washington was very conscious of the fact that his role, as it had been during the Revolution, also in the post-Revolutionary period would be to set a model. A parchment document, as he said, doesn’t set the model, it’s the behavior of people. He saw the role of a leader as being an individual that sets a framework for government moving forward.

There are three things that I highlight that he did that were really important and often forgotten when we talk about him. First, he spent a lot of time traveling the country, going quite literally from inn to inn meeting with farmer to farmer. His diary is filled with these wonderful descriptions. He was connecting citizens with a larger government beyond their local government. He wanted citizens of Massachusetts to think of themselves as American citizens. He wanted citizens of Virginia to think of themselves as Americans – they didn’t. He helped create this American identity defined by a common good government that would connect us.

The second thing that he did, and this is really important, is that he surrounded himself by talented people, and he had them focus on solving problems: building a functioning economy, putting together a functioning foreign policy apparatus to keep us out of war, dealing with rebellious farmers that didn’t want to pay their whiskey taxes, things of that sort. The play Hamilton, which I love, tends to overemphasize the ideological differences. Hamilton and Jefferson saw the world differently, but actually they worked very well together under Washington’s leadership. That’s what a great leader does, brings people together to solve problems.

The third thing that Washington did, which is really important, is that he created a foundation for the United States to develop a policy that would focus upon serving our needs, our national needs, and keeping us out of conflicts that were important, but would actually be distractions from our needs. He did not want us going to war frequently. One of the reasons he resigned after eight years was that he also wanted the country to continually remake itself.

So, he really set a pattern that was really as important as any words in the Constitution.

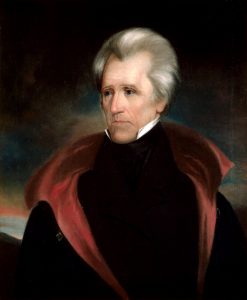

One of the 19th century presidents who really sort of breaks the mold, and brings new thinking to the office of the presidency, as you point out, is Andrew Jackson.

You could call that new thinking, yeah (laughs)

It was different, and yet not – the Populist movement was getting started and he very much was a Populist. As you point out, he was quite a mold breaker.

Yes, in some ways you can see Andrew Jackson as the “un-George Washington” figure, although Andrew Jackson revered George Washington. Andrew Jackson was the first American president who was actually born in the territory of the United States, born in the United States itself, not under the British Empire. He was also the first frontiersman to become president, he was born into a poor backwoods Carolina family. He grew up fighting Indians because the Indians were on land his family needed to survive, that’s where his Indian hatred, his racism toward Indians comes from.

Jackson believed that the presidency had become too elite-centered, that it was serving the interests of financial groups in New York and Philadelphia, and that it was serving the interest of elite East Coast individuals. And, if you look at the people who populated the presidency they were all Virginia and Massachusetts elites before Andrew Jackson. As a settler of Tennessee, he was the first president really to bring the office well beyond the traditional power centers.

Now, two things need to be said about Andrew Jackson. His Populism, as we’ve come to call it, was not rhetoric alone. That was who he was. He used the office as best he could to help poor farmers like himself when he was younger. This was not rhetoric. He did not bring financial elites into office and pretend he was draining the swamp, he was actually using the office to try to serve those who were poor and left out. That’s why that strain of American history remains so important. I argue later that Franklin Roosevelt is, himself, a populist.

The second thing about Andrew Jackson was that he believed in government. He was not anti-government. He had been a senator, he had been a general, he had been involved in writing the constitution of Tennessee. Andrew Jackson believed that government was good, he just believed that it was misguided before him in the office. He sought to work with members of Congress, and he sought to work with his own party, which becomes the Democratic party, to actually make government work. So, to be a Populist to Jackson was not to be anti-government, it was to be pro-government for the people who were left out.

Another president who comes from very humble origins, of course this is much more storied – I think Jackson has probably, by virtue of the fact that he was such an outsider, gotten a negative reputation among his contemporaries – but Abraham Lincoln also comes from very similar origins. You refer to him as a poet …

Yes! I think Abraham Lincoln was one of the most extraordinary people in the history of the world. Tolstoy says this.

okay…

I don’t mean Lincoln is the greatest person in the history of the world, but he’s one of the most interesting people. Here is someone who really has less than two years of schooling, and is probably not just one of our great presidents, but one of the great masters of the English language. It’s humbling to read Lincoln’s words and to think about how he masters the language and moves us to this day with so much less preparation than any of us listening to this recording have! And I make the point that this is absolutely crucial. He is the first president, really, to mobilize the English language the way he does.

This does not mean that language substitutes for the killing on the battlefields, but what Lincoln does is he finds the words to articulate for Americans in the north, and some even in the south, what the country is about and how they can move forward beyond what he sees as this scourge of slavery, this sin of slavery, and the horror of this war.

I just visited this summer the Gettysburg battlefield again – I do something Lincoln every summer with my family who have to suffer through this with me! What’s extraordinary – you walk through this battlefield, and I’m sure many of our listeners have to – and it’s horrible! It’s a horrible battle! More than 10,000 people die or are injured in a few days, in a place that no one wanted to fight in. But at the end, the Gettysburg Address, delivered a few months later, really turns that battle into a moment of renewal, of rebirth for the country, and that matters.

And, boy, Chris, when we’re in a world where we’re so busy to send 140 character messages to each other, we are sorely missing in the language to make us better people. I’m inspired by Lincoln to this day and, quite frankly, looking for a new Lincoln.

I love the quote you include from the president of Harvard at the time who says that the Gettysburg Address “accomplished in two minutes what I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish in two hours.” I think that really encapsulates how good he was.

And that’s what leadership is. Leadership is not about doing everything as fast as you can, it’s finding those moments when the key words make a difference. In the last few years, with a series of presidents, we have lived through presidents missing those moments, and we are missing something as a people as a consequence.

You also the Roosevelts – we have Theodore, the Progressive, and Franklin, whom you describe as the populist – as the concluding part of your “Rise” series. What makes them part of this upward trend in the experience of the presidency?

One of the things I’m fascinated by is how one generation learns from the one before. So, Lincoln in some ways, takes what he sees as the best of Washington and Jackson, and Theodore Roosevelt is a Lincolnian in every way. He sees his program as taking the accomplishments of Lincoln coming out of the Civil War, and really making them more permanent, institutionalizing them, and making them to some extent even global. Theodore Roosevelt is responsible, really, for the next stage of American industrialization, and for all kinds of progressive legislation that allows us, as we’re industrializing, to have things such as workman’s compensation, to have anti-poverty measures, and to create national parks, which are designed as spaces where people can escape from the dirt and grime of an industrial city and reacquaint themselves with nature. What Theodore Roosevelt is trying to do at home and abroad is provide a permanent for human beings to thrive in a more prospering, post-Civil War economy. He has a vision of this that is remarkably effective, I think.

Franklin Roosevelt, his cousin, inherits that system and many of the problems of that system – that’s what the Great Depression is, that’s what Fascism is: those who are left behind, those who are harmed by this system. Roosevelt makes the presidency into a healing institution. I love all the oral histories we have of Franklin Roosevelt, we have thousands of them, where people who never experienced anything like his background–people who came from far poorer backgrounds, were not elite Roosevelts–still would say, “That man understood me. He empathized with me.” Roosevelt, Franklin, recognizes that you have to marry the accomplishment and progressivism of a Lincoln or a Theodore Roosevelt with the empathy of what he represents as president. And he turns this institution into a personal institution. He quite literally brings to the presidency into peoples’ homes through the radio, and, again, anyone who lived through that period speaks of Roosevelt in those terms.

At this point, you then start discussing — the section of the book is called “Fall,” although I think that’s probably a vastly oversimplified term for what you describe. You discuss both Kennedy and our home-town hero LBJ, but as frustrated leaders who are the first to experience the down side of the office and what it’s starting to become.

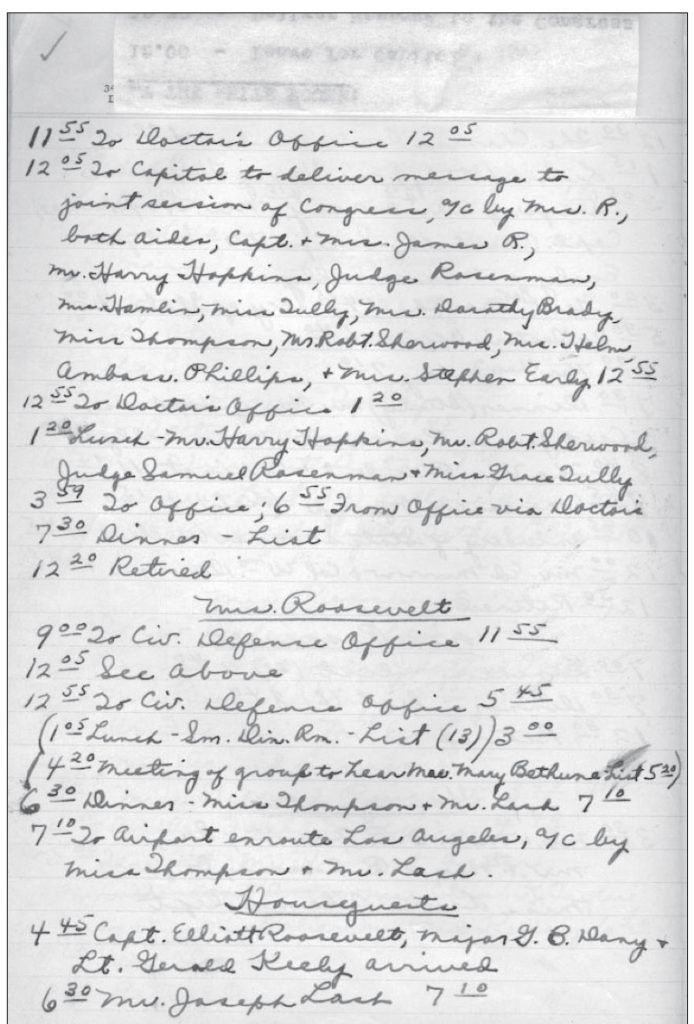

It’s quite extraordinary, Chris, to spend quite a lot of time looking at how these men organized their time. One of the great things about being a historian is that we work with primary documents, we get to actually get to look at the original stuff. And one of the original stuffs – the documents I got to look at – are the calendars that all of these presidents kept, including Franklin Roosevelt, and I have some of these in the book. Franklin Roosevelt’s calendar is written in pencil, and it looks like an old day timer’s page. Your calendar and mine are busier than Franklin Roosevelt’s. It is about the time of Kennedy’s presidency that we see, in the White House, but also in corporate America, that calendars get more scientific and more filled.

What Kennedy and Johnson struggle with is that they’ve inherited this office from Franklin Roosevelt that has done so much for the country and the world, and now it’s asked to do even more. And they are sort of on a treadmill that was already going very vast that’s been doubled in speed. And I imagine them as these men, these great runners, who are trying to keep up, but the treadmill just keeps going faster, and faster, and faster. They get frustrated, and they say this time and again, that they don’t have time to understand the issues that they have to make decision about, and they’re constantly asked to do more and more. These two men then fall into a pattern of constantly taking more on, and claiming they’re going to do more than they themselves know that they can do.

And I think that’s the beginning of the fall of the office. It creates this profound disillusionment, where we come to see our leaders as liars because they’re promising to, you know, bring sunshine in the morning, bring food in the ground, and do everything for us. And when they don’t succeed, we think they’re lying.

Exactly. You also give quite a few pages to Ronald Reagan who – I think we all recognize that he was a vastly significant member of the recent president cadre, regardless of your opinion on some of his policies – but that he also managed to keep a whole bunch of balls in the air.

-Right-

For better or for worse.

What fascinates me about Reagan is that I think Reagan had some profound insights. One of them, actually, is what we’ve just been talking about: that the office of the presidency was trying to do too much. Reagan was trying to scale back the office. You could argue that Reagan actually understood the problem as well as anyone has in the last fifty years. What I try to show in this chapter is that even understanding the problem, he couldn’t work his way out of it. He actually did remarkable things with regard to shifting American policy toward the Soviet Union, and working with Mikhail Gorbachev, which reflected his willingness to get outside of the treadmill of what the CIA was telling him, including then-CIA Director Robert Gates, and what other institutions were telling him, and he thought for himself.

But, as I point out in other parts of the chapter, he wasn’t able to do that in other areas. And he was forced, despite his own inclinations, to take positions on AIDS, for example, to take positions on poverty in the United States, and the positions he took in a somewhat thoughtless way because he didn’t take the time to understand the issues – which he could have – ended up harming thousands and thousands of people. That’s a problem George Washington didn’t have because he wasn’t asked to comment on those issues because he didn’t have power that was relevant to those issues.

So, the Reagan chapter is kind of a tragic chapter in that he sees the problem in a Shakespearean way, but can’t actually work his way out of it.

This is also a theme you have in your final chapter, which looks at Clinton through Obama, in which we’ve really found ourselves in the situation where, when the Congress is dominated by the opposing party, it almost becomes a winner-take-all scenario. And there’s a lot of frustration. Possibility, but frustration.

Right, and I argue that Clinton and Obama in particular – Bill Clinton and Barack Obama – as controversial as they are, the one thing there really isn’t any controversy about is how talented these men are. You can like what they were doing with their talent or not like it, but these are enormously talented men, and I point out in the chapter how they’re a phenomenon. They’re like that great tennis player who happens to grow up in a poor inner-city area and all of a sudden walks on the court and there’s this extraordinary player. They bring such skill and talent to the table, but that’s also the problem. Because they overrate what they are able to do.

Both of them underinvest, I argue, in trying to reform institutions and build the kinds of partnerships they need in office to get things done. They overinvest in their own ability to keep a lot of balls in the air and make a lot of quick decisions, and that ends up coming back to bite them, I argue. Instead of investing in structural reform, it’s too personalized. And I blame the electorate as well, both those who love them and those who hate them. The real problem when we get to the post-Cold War world, Chris, is that we have personalized the office and we expect the problems of the office, which I have argued are historical, to be solved by individuals. And here’s what I say as a historian: historical problems are never solved by individuals. They’re solved by broader efforts at historical reform, which involves institutions. Which involved groups of people. And that’s, I think, why we have now started electing people who promise change, because of who they are, or who promise to blow up the system, because of who they are, rather than talking about actually reforming it, which is what we need to do.

What is the path toward the reform that you suggest?

I think the great presidents of our past, during our period of “rise” – we might say – recognized that the office had to be remade to serve the needs of those who were not being served by the office. It is quite clear that large numbers of Americans feel that the president, no matter who he or she is, is serving only their interests. It’s time we address that. That’s what our health care debate should really be about. There are tens of thousands of Americans who are in situations of health tragedy. That’s not to say that one system is better than another, but the office needs to address that in ways that he hasn’t before.

The same is true with the international system. We live in a world that’s more conflict ridden, and too often we have just thrown our military force around because it’s quite frankly the easiest thing for the president to do. We need to reform the way the office manages things like diplomacy and other elements of American foreign policy. The office needs to connect to people and the purposes of our country.

And our next presidential election should not be about who has the best one liners on every issue, but about what our priorities are and which individual is best suited to help us reform our institutions to best serve those who are left behind, and best protect the security of our country. It’s astonishing to me we’re not having that discussion, but if we had a Lincoln, he wouldn’t do what Lincoln did, but he would find the words for us to have that discussion.

More on The Impossible Presidency:

An excerpt from the book on Not Even Past.

An interview with Dr. Suri on CSPAN.

The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office (2017)