At the height of the British empire, India was considered the jewel in Britain’s crown. For over 150 years, a handful of British troops maintained control over a country of 300 million. Finally, after two world wars and a popular independence movement, Britain abandoned its imperial project and withdrew from India in 1947. What was Britain’s motivation in keeping India, and how did they accept the inevitability of losing their most valuable colony?

Guest Snehal Shingavi from UT’s Department of English examines the nature of British colonialism in South Asia and its lasting legacy sixty years after decolonization.

Guests

Snehal ShingaviAssociate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Texas at Austin

Snehal ShingaviAssociate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Before we start off, could you give us a brief history of European imperialism in South Asia, to set the stage for what we’re going to be talking about in the 20th century?

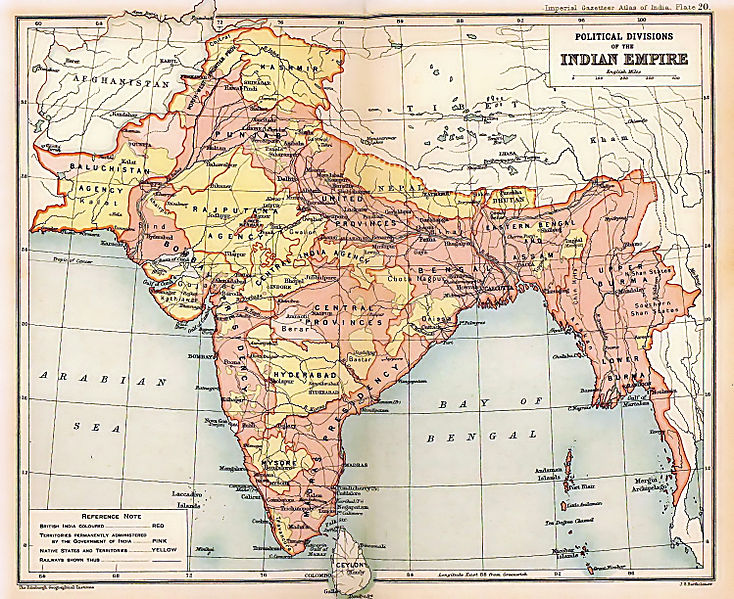

Asia is always an important place for Europe. It’s been interested for at least 500 years in commerce, in resources, in its mineral wealth, and also in its people. Over the course of the 17th, 18th, and 19th century, began to consolidate its naval routes into Asia, all of which centered on India being a primary place where ships would stop and either trade or refuel. By the middle of the 19th century, the British East India Company has acquired enough political and economic power that they actually have to fight some fairly substantial political campaigns. The largest of these was the 1857 battle, what is called in India “The War for Independence,” but is usually referred to by the British and Americans as the Sepoy Mutiny, where soldiers who were paid by the East India Company to be their armed forces rebelled against the East India Company. At that point, the British government sought fit to take over control of India from the British East India Company and consolidated then what is called the British Raj. They began to run the country from England for the next 90 years.

How was Britain able to maintain this power from such a great distance? Was it manpower–people that they sent over–was it the use of local elite classes, or some combination of the above?

This is the question that has always befuddled Indian nationalist historians: how so few British men–less than 100,000 British men–were able to control a country of over 300 millian people. Part of the way the British were able to do this has to do with three things.

The first is economic and industrial superiority that the British had because of the industrial revolution very early on. It allows them the technological capacity to send troops over whenever they need to, but also to run supply lines for their own military. It gives them immense military capacity and allows them the ability to control.

The second thing, and this is the most important thing, I think, from an historical standpoint, is that India is not one nation when the British arrive. It’s actually divided up into smaller princely states, many of which are at war with each other. The British are able–pretty successfully–to pit smaller states against one another, and to design treaties with larger states, and the larger political infighting allows Britain to consolidate its power much more easily than it would have been able to if it had to do this entirely on its own.

The third thing, importantly for British military rule, is that they are able to siphon off a class of Indians from the middle layers to become ambassadors for British rule in India. It’s a class of ambassadors who are trying to think about industrialization, education, modernization, who see the advances that Europe has made and want similar things in India, and they began to support British rule.

These three things help the British substantially in maintaining rule over a very large country for quite some time.

What role did India play within the larger British empire?

India is famously called the Jewel in the Crown of the British empire, and it has three basic things that it provides to the British that strategically make it important enough that the British held onto it for as long as they did with such a tight grip.

The first and the most important thing that it provides is naval routes into the rest of Asia. Because Britain holds India, it’s able to send its navy, its air force, and its troops all over the Indian Ocean, everywhere from the tip of Africa to Southeast Asia.

The second thing it provides is human labor power. Labor, not only in the sense of Indians who were sent to work on plantations starting in the middle of the 19th century when Britain outlaws slavery — slaves started to be replaced by Indian indentures workers in areas under British colonial possession. Most of the places in the Caribbean, Africa, and Southeast Asia where you see large South Asian populations, they’re the result of this indentured migration — but also in the sense of military recruitment. India provides one million soldiers for the British during World War I, and two million during World War II to fight in the European theater and also in the Middle East. Famously, the British campaign in Mesopotamia / Iraq is done by Indian soldiers.

The third thing it provides is massive amounts of economic resources for the British. It provides markets for their industrial goods, it provides raw materials that they need to process, and it allows Britain to essentially become a premier economic power. In fact, its industrial capacity and success depends in large part on its control over the economic success of India.

You touched a bit on India’s importance during the world wars, but can you talk a little bit more about the impact that the world wars had on Britain’s imperial project, with respect to India in particular?

During World War I and World War II both, Britain plays a pretty major role but takes a pretty severe beating as a result of how devastating it is. Even though it comes out on top in World War I, it’s at a pretty severe cost to the strength of the empire. It also proves to most Indians that no matter how loyal they are to the British crown, Britain is not going to take Indian demands for independence seriously. It does a bunch of things both to the infrastructure of the British empire–in terms of weakening it in certain places–but it also reinforces for many Indians what the cost will be for India if Britain continues its global imperial project. Many Indian politicians said famously that India was bled dry in order to finance Britain’s campaigns in World War I.

In World War II, there are massive famines that happen all over the country, not because there’s lack of agricultural production, but because food is literally taken from India and sent to English. So, the war has an economically devastating impact on India but also, and it’s important to point this out, Indian soldiers are returning from the war now with some military experience and confidence that they should be entitled to the same benefits that British soldiers are getting when they come back from the war. When that doesn’t happen, it really does strengthen the demands for Indian independence.

The last thing that I want to say, though, is that I think that the untold story for India’s independence is really the mutinies that are taking place by Indian soldiers during World War II. Famously, the Royal Indian Navy and the Royal Indian Air Force both mutiny in important ways at the tail end of World War II, and this convinced England that it’s no longer going to be able to hold on to India militarily. The costs of the empire are at direct odds with what they need infra-structurally to keep the imperial project going.

We know from history that Britain abandoned its empire pretty rapidly after World War II. They pull out of India, they pull out of the Middle East–in both cases with pretty disastrous consequences. Was this an outgrowth of the war? Was this something they’d been considering with the change of leadership from Churchill to Atlee in London, that suddenly there was this will on the part of the colonizers to abandon the project? How did that come about?

There are three parts of this story that are important to tell.

The first is that Britain does not have the capacity to hold on to chunks of its empire, and it’s making choices about what it can hold and what it can’t hold. Part of that decision making calculus is being determined in Whitehall, in as smart a way as they can make it (I think). I don’t believe for a second that Churchill was somehow more or less compassionate than anyone else. The British economy depended so greatly on what India was able to do that even the most liberal minded of British politicians, I don’t think, wanted to let India go.

The second thing, and the one that I think most people know, is that the campaign for independence inside of India was massive. Millions of people are out in the streets campaigning for freedom, for liberty, for the lack of colonial interference in politics. Gandhi’s campaigns are immensely popular globally, and this makes it very difficult for the British to keep a lid on nationalist sentiment. In some places the ruthless repression of the nationalist movement basically watered the soil and more and more nationalists grew out of it.

During World War I there were aerial campaigns against centers of nationalist agitation; during World War II similarly they were very worried that sections of India are going to hook up with Japan, and make India a new front in World War II, and that’s all happening because of nationalist agitation within India and trying to find new ways to work this out.

Thirdly, it seems to me, that global politics was really beginning to change, and Britain’s position is now being eclipsed by new superpowers that are setting the terms of the debate and how the game is going to be played. Britain has to abandon much of its imperial project in the Middle East and South Asia because Soviet influence in the region is growing massively, and it settles for having a rearguard position in Africa as its primary colonial possession through the 1950s and 60s.

These are all calculated decisions that are made because of national, international, and regional politics that are changing after World War II, and the re-division of the spoils of empire that happen. The US and the Soviet Union are basically determining how the map will look.

You kind of foreshadowed with your term “re-division of the spoils:” as part of the decolonization of South Asia, India was partitioned. How did the actual independence process move forward, and how was partition accepted as the inevitable outcome of it?

This is a tougher story to tell quickly. Suffice it to say that part of the British strategy in controlling India had been to suggest that seats at different levels of power ought to be divided between Muslim and Hindu constituencies. Convincing certain people that Hindus and Muslims were separate populations, constituencies with different interests … elections to certain posts involved cultivating a base of people within a certain religious identity vs. those of another religious identity.

This was a construction by the British of two separate groups of people. And, as it’s becoming clear that India is going to get its independence–come the early 1940s, it seems like the writing is on the wall–these constituencies were vying to see who was actually going to come out on top at independence. Cynically, both conservative elements within the Hindu constituency, and within the Muslim constituency, are riling up their forces to demand more of the division of what will happen after independence. The inability of the nationalist movement–the Congress Party specifically–to offer solutions that spoke to ordinary Muslims and ordinary Hindus in meaningful ways meant that deals were cut between the British, the head of the Muslim League, and the heads of the Congress Party to determine how India would be divided.

There are still princely states within India; these princely states then had to decide which side they would go to. Lord Mountbatten came down, maps were drawn hastily, and the whole thing was a chaotic political blunder because of how fast the process of decolonization went. It ended up meaning that Hindus who lived on one side of the border, and Muslims who lived on the other side of the border, are trapped in what is still today one of the bloodiest and largest campaigns of ethnic cleansing. Hindus flee what then becomes Pakistan, and Muslims flee what then becomes India.

The other part of this that I think is worth mentioning is that South Asia–what the British Raj was–included not only what became India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, but also Sri Lanka, Burma, bits of Nepal. Decolonization and partition didn’t happen all at once; different bits were carved out to be different administrative regions. The legacy that we now have are populations divided by arbitrary borders. This is a legacy of how the British conducted the decolonization campaign.

You mentioned that the British brought in their economic and industrial superiority, and this is one of the things that allowed them to dominate India. What are the lasting impacts of this colonial legacy on India today? Obviously, India itself is something of a regional economic power-which is something that we don’t necessarily think of when we think of Pakistan or Bangladesh. What are the lingering effects of those colonial institutions that we can still see?

Many. The political institutions that India has are inherited from the colonial apparatus, so the parliamentary system that it has, the courts that it has, the way its own military is organized are all inheritances from British rule.

Economically, the British like to claim that they did a lot for India, but the fact of the matter is that the infrastructure that they built was not terribly helpful for economic development. The railroads didn’t go where they would be helpful for economic growth, they were basically useful for transporting raw materials out of the country and finished materials into the country, not really for the economic development of the people there. But what it did allow is for massive amounts of intellectual, personal, and financial relationships to be built as Indians began to migrate to different parts of the British empire. So, the British built a limited educational system in India, it did mean that there was a class of Indians who were educated in English, traveled to England, set up shop in England. These global connections that were built over the vast spread of the British empire allowed India to access some major entrepreneurial and business talent, scientific talent as well, which helps India in the moments after independence to grow pretty substantially.

Pakistan doesn’t have the same sorts of resources for two reasons. One, the schools that the British built weren’t built in Pakistan the same way they were in India, and two, at the moment of partition, what becomes Pakistan inherits some of the worst agricultural land and none of, or very limited, industry that the British built. So, Pakistan economically starts the game well behind India. At the same time, I think it’s worth saying that many of the social problems that exist within India today are direct legacies of British colonial rule. The caste system, for one thing, most people like to think of as a kind of timeless thing that existed in India, but it was actually quite fluid. It definitely had some problems, but the heirarchicization and the codification of it into law really was something that the British put into place while trying to figure out how to administer the region. They developed constituencies on the basis of caste. There are debates about whether or not what were then called Untouchables, but are now called Dalits, should be a constituency or not. They carved out different populations this way, and the modern ways that caste plays itself out in politics are a direct result of British meddling in the social organization of India.

What is called communalism, or the conflict between Hindus and Muslims, continues today as a direct result of what was done by the British.

The last thing to say is that the tragedy of the fact that certain peoples who were never part of India or Pakistan were forced to become part of India or Pakistan because that’s how the British parceled out the land. They’ve been fighting for their independence since 1947, if not longer. You think about Baluchistan, in Pakistan, the North West Frontier Provinces, Kashmir, Assam, the northeast of India, these are all places that the British annexed into the states that the British thought they belonged to. One of the other legacies has been its incompleteness: this is still the incomplete part of the decolonization process.