On June 23, 2016, British voters stunned many political observers (if not themselves) by voting to leave the European Union. To many outside observers, the election result was unthinkable, provoking a major political shakeup in the UK as well as an identity crisis within the EU. The factors that led Britain’s electorate to reject the EU, however, are rooted in decades of uneasy alliance with former rivals and enemies in the European bloc.

Philippa Levine from UT’s Department of History and Program in British Studies walks us through the contemporary British politics and rocky history of Britain and the EU that contributed to this historic decision.

Guests

Philippa LevineMary Helen Thompson Centennial Professor in the Humanities, UT-Austin

Philippa LevineMary Helen Thompson Centennial Professor in the Humanities, UT-Austin

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

We’re going to be talking today about Brexit and I’m going to take the unusual step of date stamping this episode because things are changing so rapidly . It is July 14th [2016]. Yesterday David Cameron resigned as Prime Minister of Britain and Teresa May became the Prime Minister. And this is a story that has been changing really fast and it might be another seven weeks before this episode gets published so I just want to let everyone know where we are in history if you will. Let’s talk about Britain and the European Union, so that we can understand why Britain just voted to leave the European Union. When and how did Britain join the EU and was it the EU at that time or was it just the EC? There have been many precursors to the body that we know know.

Indeed. Absolutely. So a quick history. In 1951, not long after the Second World War, Europe is feeling a little bit bruised a lot of anti-communism around, America is becoming the new super power. Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, signed a treaty. Its a very boring treaty, it’s a coal and steel treaty, but the idea was that they could manage the heavy industries, the really important industries that were kind of central to the economy, together better than they could as separate countries. And it’s interesting Germany is in there as well, of course the country that has lost the Second World War, so it’s an attempt also at rebuilding and healing Europe.

Britain’s not in the picture at this point. Britain at this point of course is in many respects still struggling with its empire. It’s in the process, a very long drawn out process, of what we call decolonization. Its rapidly losing parts of its empire. India’s already gone, Palestine’s gone, a few other places, and many more are to come. Britain is kind of dealing with all of that stuff. In 1957 those coal and steel treaty members, half a dozen European countries, signed something called the Treaty of Rome and it was that that led to the creation of what at the time was called the European Economic Community, or this is a phrase that many people will be familiar with, the Common Market. And that was what it was called until really until the middle of 1990s when the European Economic Community became the European Union.

Now Britain twice retried to join in the 1960s. It was clear by the 1960s that the empire was dissolving around them in many ways and so Europe is just across the water. It really is, you can swim the channel if you’re a good swimmer, and so we’re very close to France in that respect. On a good day, and there aren’t many of those in Britain, but on a good day you can see if you’re on the cliffs of Dover, you can sort of see where France is. They’re very very close to Europe in that sense. And Eastern England is very close to The Netherlands and so forth and so on. So in the early 1960s Britain tried to join the European Union and was promptly turned down. The biggest opponent was De Gaulle, the French Premier, who felt that Britain was still too welded to its empire on the one hand and to the US and very much in the US’s pocket after the Marshall Plan and the financial borrowing that had gone on, so he vetoed them in 1963. They tried again in 1967 and once again De Gaulle said no. That year, in 1967, the European Economic Community changed its name to the European Community, so it goes from the EEC to the EC, same year 1967. It took De Gaulle getting out of power for Britain actually be able to join what had become the European Community at that point. And they finally joined in 1973 along with Ireland and Denmark.

It was a conservative government, Edward Heath was the Prime Minister at the time, the Prime Minister of course is the chief minister in any British parliament. Edward Heath who was the conservative or Tory — as we call them — MP at the time took them in. So it was a conservative who took them in and it was a conservative who essentially although accidentally took them out in 2016.

So they join in 1973 but what’s interesting and the slight kicker here is that two years later when a new government comes to power, and this is a Labor government, so the conservative are the right wing dominant party in Britain, the Labor party is the dominant left wing party in Britain. Labor had come into power in 1974 after a really bruising set of strikes shortened work weeks. It was a really ugly period in British history. Harold Wilson who was the labor Prime Minister who came in decided to have a referendum to see whether Britain should stay in the European Union. What’s interesting of course is this was the first ever referendum in British politics so this is really interesting sort of set of things going on where the two bits of this look the same. So in 1975 there was a referendum and 67% or there about voted to stay in what was then called the Common Market and it’s interesting to see how that broke down. The support for staying in the Common Market at that point was conservative and right wing for the most part. The left of the Labor party actually pledged that they would withdraw from the Common Market, from the European Community if they got the chance. And in fact it was in the manifesto of one of the subsequent labor leaders, a left winger called Michael Foot who subsequently died, but his pledge was that he would take Britain out of the common market.

What was the impetus to join the Union? They tried three times so they must’ve really thought it would be a good idea.

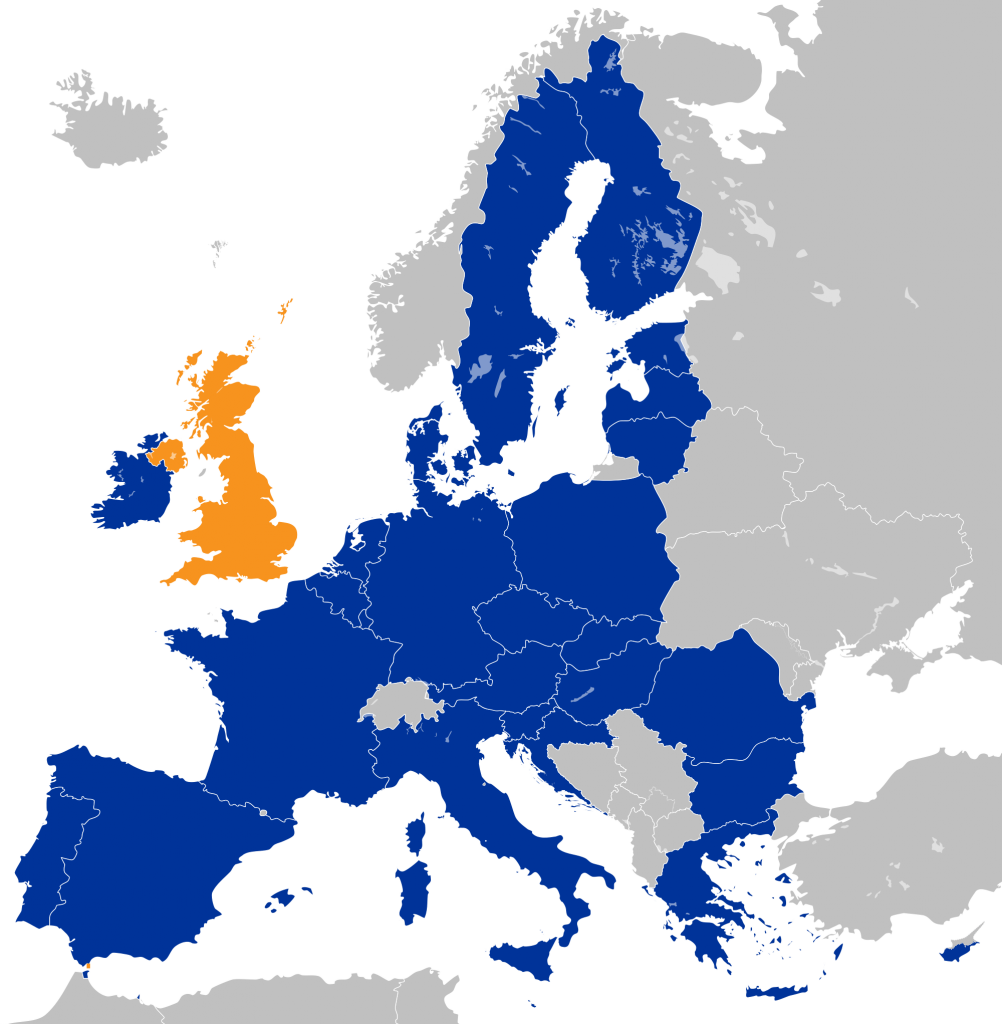

By the middle of the 1960s, when it was clear that the colonial economy was not really going anywhere anymore, they had the Commonwealth, which was the former white settler colonies who were bound together in some sort of position, but essentially they need the economic impetus that came from being part of this market. They realized that proximity as an island, but as I said very very close to Europe, that they would disadvantage themselves if they didn’t become part of this rapidly growing environment. It’s worth noting that today– Britain’s still in or Britain’s not out yet — but right now there are 28 countries. There were then, it was growing and most of Europe wanted in and so it was clear that this was going to be an economic power house for the future and not to be part of that for Britain, which remember also was losing its status in the world with the loss of its colonies. It was becoming a kind of second-rate, second-class country without the kind of power and influence that it had had, that had in a sense been ceded to the US in large part at the end of the Second World War, but increasingly also to this increasingly United Europe. And again not just 28 countries but today 507 million people in the European Union. That is a power house.

–which is as large as the United States again by half

–and its GDP is very, very significant indeed. I think the largest in the world.

After joining, after the referendum said, ok, we should be here, we want to be here, what was Britain’s relationship with Europe like? For example, they’ve excepted themselves from a lot of the rules. They’re not part of the Schengen customs agreement, they’re not part of the Eurozone, so that speaks to not a full contentment.

I think that’s exactly right Chris. I think the relationship between Britain and the European Union has always been a tense one, an uncomfortable one and in some ways a kind of partial one. Britain wants some of what the EU has to offer, but not all of it. And there have been a series of embarrassments, clashes, all sorts of things. Here are a few examples. In 1988, for example, Margaret Thatcher, who was then Conservative Prime Minister of Britain, made a stinging speech in Bruges, rejecting what she called a European super state. In some ways it was the end of Thatcher.

She doesn’t get kicked out for another couple of years, but she was rapidly becoming what today we call a Eurosceptic and most of her cabinet was still Europhile and it was one of the things that actually brought her down. So she had made this criticism of Europe about the ways in which it was making laws and deciding things for the group as a whole and she was uncomfortable with that. Then a couple years later, in 1990, Britain joined what was called the Exchange Rate Mechanism and it had to withdraw from it a couple of years later because it couldn’t control currency speculation that happened at the moment of introduction of the Eurozone. It was called Black Wednesday and it was a moment of deep humiliation and embarrassment for Britain. So they weren’t happy with Europe over that they of course don’t join the single currency, the famous Maastricht Treaty of 1992.

There’s also in 1999 a few years later, lots of tension with the EU, particularly with that old foe France. They’d been at war with France since the 18th century and De Gaulle had, of course, as I said, twice rejected joining the EU, but in France in 1999 at the time of the big mad cow crisis when people were getting here horrible brain diseases from eating infected, tainted beef, France banned all imports of British beef. So the Union is kind of cracking there in many respects but Britain was deeply deeply unhappy about that.

And so there have been these constant tensions — as you say they didn’t join the Schengen zone, they didn’t join the Eurozone, they’ve kept themselves apart in those ways and much of the debate has been about this idea of what the British like to call “sovereignty.” This idea — that one is deciding one’s own fate and it isn’t being made by faceless bureaucrats over there in Belgium. What the difference to me between faceless bureaucrats in London and Belgium is seems to me a little interesting but that’s been a lot of the rhetoric behind this campaign in the last few months.

Would it be fair to say that internal British politics played a role in why this referendum took place now?

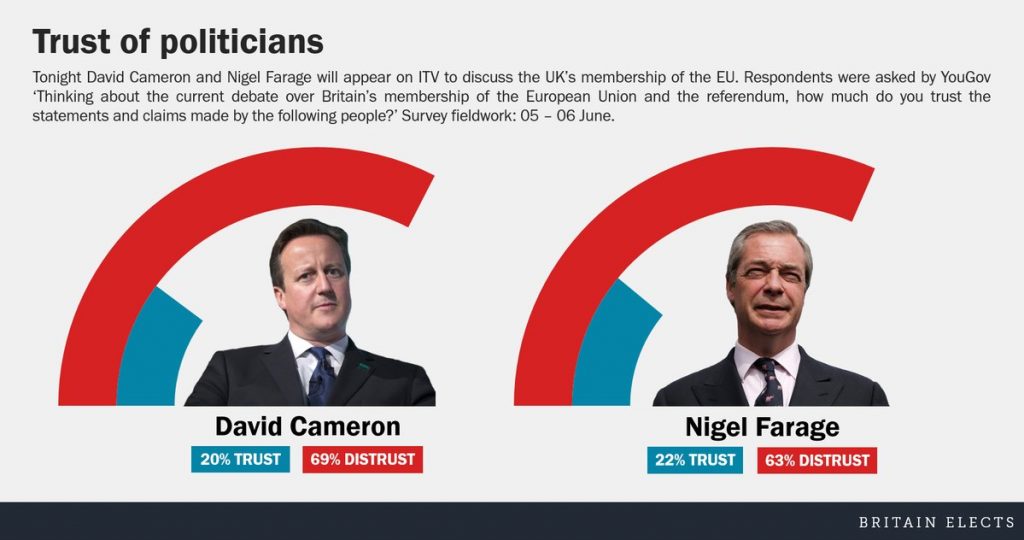

I think there’s absolutely no question about that. David Cameron the conservative Prime Minister who resigned yesterday, the 13th of July, Teresa May has, of course, become the Prime Minister today as you said in your introduction, Cameron made a pledge in his manifesto for the 2015 general election that he would have an in-or-out, or an up-or-down vote on this if he were reelected. He was playing to the right wing of his party he was playing to the fringe of his party the right wing fringe of his party because he was worried about the increasing success of a newish party called the United Kingdom Independent Party known as UKIP, this is the Nigel Farage party very very active in the campaign as you all know. And he knew that he was losing people on the right of his party to UKIP. UKIP was getting stronger, Farage was an MEP, he was in the European Parliament, got booed there of course a day or two after the referendum. So Cameron had made that promise it was part of his election pledge and it was done because he was worried about splits in his own party and about the loss of his right wing. So there’s no question that inter-party politics played quite a roll.

The other thing that played quite a role has been the Scottish and Irish question. You may recall, a year or so ago there was another referendum in Britain. Britain’s only ever had 3 referenda, two on the European Union, one on whether Scotland was going to secede and become an independent country. Scotland is now reeling because it stayed in the United Kingdom because it saw the United Kingdom as being part of Europe and it wanted to stay in Europe. So there are two sets I think of internal politics, one to do with the notion of what constitutes a United Kingdom and the other to do with Cameron’s understanding of where he stood in relationship to his overall conservative party membership that I think have played a really significant role in this. Many people have actually said that Cameron was deeply irresponsible in even holding a referendum of this kind, I would have to say I hew to that position.

As we saw, the vote was incredibly close and the results seem to have surprised even those who were campaigning to leave. So what do we make of this? Or is that the million dollar question right now?

I think that is the million dollar question, but I think there’s really interesting things to be said about this. Let me just recap what that vote was for somebody who perhaps was on Mars on perhaps living under a rock the last two weeks, I stayed up of course all night til 2 in the morning waiting for the results as you would expect when you hear my accent, you know why I was staying up as I suspect many people here were. 52%, about 17.1 million people voted to leave and about 16 million, 48% voted to stay. The turnout was a little bit less than they thought it would be. It was in the high 70%s. They predicted a turnout a little bit higher than that. It’s still extraordinarily high for any standards for a modern election in a country that doesn’t have compulsory voting.

What to make of it? Well, most the political pundits, most of the commentators, most of us in Britain thought that it would close but that it would be close the other way around and you’re absolutely right that many of the “leave” people, you could see it in their faces that morning. Boris Johnson was the classic, he looked like a deer in headlights that morning, he looked shocked, he looked flustered. Nobody expected this to happen and there has been speculation, and it is speculation, that in fact the leavers didn’t know what to do, didn’t have any plans, because they never thought that this would happen. And many people speculated that in fact BorisJohnson didn’t really want to leave. He was just using it to further his own career and didn’t really know quite how to deal once it happened.

Why did it happen though and I think that’s the really interesting question here and I think it’s worth thinking about this because I think there’s a global message here that isn’t just about Brexit. I think we’re seeing some of the same discontent in many other places including right here in the United States and I think it’s fueling some of what’s happening in our own presidential election right now. Many of the people who voted to leave were in a number of groups. They tended to be older, they tended to be in the north of England, and they tended to be working class. They tended to be people whose jobs who have been taken away from them, not by the European Union necessarily, and not by the European Union really much at all, but by the ebbing of heavy industry and manufacturing and those kinds of things within Europe generally in the space of the last 30-40 even 50 years. So it’s a group of people who have lost ground economically, politically, socially in many ways but look at London and other capitals around Europe and see that they are awash in money. One of the things that has really been striking in the last 20-25 years, a little bit longer than that even in Britain, since the Thatcher era, the gap between rich and poor has become very wide indeed and the poverty has become really quite a serious problem and they look around and they see, they perceive, that the super rich in London don’t care. Nnd so it was a vote of protest. tThere are other things going on as well but there’s a real economic and political vote of protest about not being heard, not being respected within the system. And I think that’s one of the principal reasons that we saw this mass working-class revolt, essentially, it’s an electoral revolt, but it is a revolt. There are other things going on, there is a kind of racist anti-immigration politics in here as well. There are concerns about the particular economics, there are concerns about sovereignty, but mark my words this is a working-class vote of discontent and it could happen here.

As you point out the vote is about sovereignty but at the same time there is a lot of speculation now that the United Kingdom may cease to be. You’ve got Northern Ireland which, Britain’s Brexit if you will, threatens a lot of the arrangements of the Good Friday Accords and Scotland who’s already talking about another secession referendum because there wasn’t a single precinct in Scotland that voted “leave.” They all voted to remain in the EU. So there’s a huge irony here.

It’s very interesting and we don’t know of course what will happen, but indeed this could mean that the United Kingdom cease to exist as a political and constitutional entity. That is quite possible, I think, Chris. We could end up with 4 separate parties, or England and Wales with Scotland as a separate country and there’s a lot of talk about that in Scotland. I have Scottish friends who voted to stay within the United Kingdom who are now saying, that’s it. And they were saying before the referendum that if England and Wales vote “out” then I will vote to leave [the UK] the next referendum because they feel there will be one.

It’s particularly difficult for Ireland. One of the advantages that Northern Ireland has enjoyed, as a result of being part of the European Union, has been the open borders between it and its southern neighbor. Because remember Northern Ireland is just a few counties in the north of the country and the rest of it is southern Ireland which of course is an independent country, has been since the 1920s and is part of Europe and will stay in Europe, and joined at the same time, by the way, as the UK. Now if Britain comes out of the EU which looks as if it’s going to happen, we assume that’s what’s going to happen. Teresa May has said she will trigger Article 50. If that happens, those borders will close. Those borders closing will bring back some very very painful memories for people who remember until very very recently all of the troubles and violence and anger and desperation of what was going on in Ireland as those counties fought for independence from the United Kingdom. So two things: on the one hand the borders will close and that’s going to make life very difficult just on a daily basis. People go between Belfast and Dublin, and wherever, all the time and you could just do it at the moment, I’ve done it myself, but they won’t be able to. There will be border checks and so forth and so on, but it may also revive some of the concerns that people in Northern Ireland have and they may now re-open the fight to secede and join Ireland rather than stay within the United Kingdom.

Wales, of course, voted “leave” and there are very good reasons why. The coal mines are in tatters, manufacturing is in tatters, it’s a very poor community in many ways. We know why Wales voted to leave and of course the irony is it’s going to lose its EU subsidies, which had been keeping it going. But England and Wales could end up as a much diminished independent country and what that will mean economically and politically in terms of the world I don’t know. Now the Remainers are saying that’s a really bad thing. The Leavers are saying no — no we can then negotiate much better trade deals with other parts of the world . Well maybe, but England and Wales is pretty small, and not all that significant in an era in which coal doesn’t matter that much, in which heavy industry doesn’t matter that much. I’m not sure what the basis of that economy might be.

I won’t ask you to look into your crystal ball and try to answer this question. We’ll just have to sit here a year from now and do a follow up episode and see how this has all unraveled, but I’d love to thank you for being with us in the studio and talking more about this. This has been another episode of 15 Minute History and we’ll see you next time.

Teaching younger students?

The Digital Speakers Bureau has an episode on Brexit that’s great for classroom use, also featuring Philippa Levine. Check it out!

Be sure to visit the Digital Speakers Bureau for other videos ready for classroom use, too!