In the waning days of China’s Qing Empire, a riot broke out in Changsha, the capital of Hunan Province. After two years of flooding, a starving woman had drowned herself in desperation after an unscrupulous merchant refused to sell her food at a price she could afford. Three days of rioting followed during which symbols of Qing power were destroyed by an angry mob, which then turned its sights on Changsha’s Western compound. Historians have long assumed the mob was controlled by the landed gentry, but as nearly every dictator knows, a crowd has a mind of its own.

James Joshua Hudson, Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Knox College, describes the riots and some surprising finds he made conducting fieldwork in Hunan that offer a glimpse into the deeply layered tensions on the eve of the downfall of the Qing dynasty.

Guests

James Joshua HudsonLecturer, University of Tennessee-Knoxville

James Joshua HudsonLecturer, University of Tennessee-Knoxville

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

We are going to be talking about Hunan province, in China. What specifically are we going to be talking about?

Well there was a Rice riot that occurred in April 1910 in Changsha, the capital city of Hunan province. Changsha’s modern developments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries is the topic of my dissertation. There’s a chapter on this rice riot, and it’s also the subject of an article that I recently published.

So, for listeners who might be not be familiar with the geography of China, Hunan is located in the south part of China, sort of in the hinterland. It’s a province that, during this time hadn’t had a lot of contact with the West. It’s an agricultural province, a lot of China’s rice production comes from Hunan. There’s also mining that’s very prominent part of the economy there and it’s also famous for its spicy food.

So, how big of a city was Changsha at this time?

It was the capital city and at this time it was probably two to three hundred thousand.

So, what happened in 1910 with these riots over rice?

To talk about what happened in 1910, you need to go back a little bit to set up the context.

Hunan was a hinterland province, and hadn’t had much contact with the West. But, it has a major river that flows north up into the Yangze River. Western countries—Britain and Japan, which was becoming an East Asian colonial power in its own right at the time—they wanted access to this river coming from Changsha because because it flowed up to the Yangtze River and onto a Treaty Port called Hangkou. It had a reputation for being anti-Western. There were anti-Christian and anti-Western riots that happened when the first missionaries tried to enter the province, and it didn’t go well.

In 1904, Changsha city opened as a treaty ports. The Western buildings were in a concessionary area. They were built with a lot of money, and this caused a lot of resentment particularly with the carpenters guild because the carpenters that were contracted were brought in from other cities. This really upset the local labor force of carpenters. That’s part of what was happening.

The other part is that rice was being exported out of Hunan for-profit, and it was controlled by these local gentry merchants. One of them was this man named Ye Dehui. He was very wealthy, and he had a bad reputation among some people in the city for being a greedy rice merchant. Merchants like him would own these large rice store houses. There was a whole system of granaries that existed in the city, some big, some small. He owned one of the biggest ones. During the riots there was a major shortage of rice and imported grain.

The other thing I should mention is that there was a big flood that happened in 1909. It caused a lot of peasants from the countryside to flee into the city. They built shanties outside the south gate of Changsha. Chinese cities at this time were still surrounded by walls and gates. The south wall of Changsha was kind of a gathering area for people who were coming from the countryside, for travelers coming from the south. Also outside the South gate there was a shanty town along a ridge called Hungry Stomach Ridge. A lot of poor people lived there. There was a pond outside called Laolongtan Pond. It was there in the early days of April 1910, that a woman took her own life with her two children because she had tried to purchase rice from a local granary owner. She was refused by him because two of her coins that she tried to purchase with were not very good quality. She was able to go and find some better coins, but when she came back, he told her that the price had of rice had gone up just in that short time. And she was so desperate that she committed suicide. Her husband was a water carrier who found out about this later in the day, and he became so distraught over his wife and children committing suicide that he also took his own life.

News of this spread through the city and people became really upset. They were upset at this particular greenery owner named Dai Yishun. And a few days after that, another woman got into and argument with Dai Yishun at this granary over the same thing, buying rice. Women at this time were the main puke procurers of food. She got into a big argument with him, and a crowd gathered and it turned into a full on fight. And they attacked Dai Yishun and they pillaged his store. And beat him nearly to death. The urban commoners who rioted use that as a pretext to eventually mMarch onto the government compound of the city.

With got a very volatile mix. You’ve got the—as you describe—this indigent lower class who, basically fled to Changsha because their land was wiped out in this flood. Prices are at a premium, the rice houses are price gouging people, and they’ve all converged on the government compound. Where does the resentments against the foreign enterprises kick in, or is that just part of the anger against authority?

Two kinds of resentments were expressed on the part of the rioting commoners. One was on the part of local government for allowing westerners to come into the city. This is also the time when resentment toward the last dynasty of China—the Qing—was kind of at a high. People were just fed up with the Qing government. This was the year right before the revolution of 1911, which brought down the Qing and the first Republican government was established. A lot of the commoners who rioted were members of these carpenters guilds, who had been cheated out of work.

A lot of the research in this chapter came from these oral histories conducted in the nineteen seventies by this middle school teacher named Liu Duping. Some of the people that he interviewed were either eyewitnesses or participants in the rioting.

What kind of foreign businesses were there? Were they exporting rice, and was this part of the resentment?

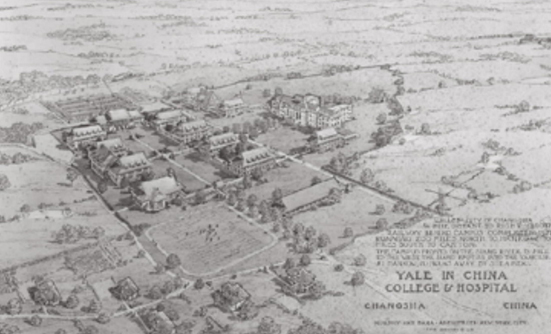

There were import/export companies, there were oil companies. Companies like Jardine Matheson, Butterfield and Swire–two prominent British import/export companies. Jardine Matheson’s building in Hong Kong is one of the most prominent buildings there today. Amco, several Japanese shipping companies. There were also foreign missions. The most prominent foreign mission in Changsha at the time was Yale University which, in 1904, had set up a mission there. It was a medical mission: they built a school, hospital, and a medical college that went on to become Yali Xiangya medical College. This established Yale’s presence in the city, one that still exists.

I want to come back to the oral histories in a moment. So what is the trajectory of the riot? What happens?

The woman committed suicide on April 11, 1910 and the riots began shortly thereafter. They lasted for about three days. Most of the oral histories cover the attack on the government compound, during which the governor of Hunan fled, and his lieutenant governor had to take his place. On the third day of the riot, things started to settle down. A lot of the conspirators, the rioters who attacked the government compound were rounded up and shot.

One interesting thing about this riot is that Mao Zedong, who became the future leader of China, was a young middle school student at the time, and he reflected years later in an interview with Edgar Snow that this riot impacted his revolutionary understanding of history.

You mentioned that they converged on the government compound. What happened there?

Well, the Qing government compound in Changsha at the time was a walled city within a walled city. It didn’t have much contact with the outside world. A lot of the officials and runners that were working there were all people from outside of Hunan. There was a policy under imperial rule that went way back called “The Rule of Avoidance,” under which local officials working in government or politics would be appointed from outside the province to avoid the appearance of favoritism. So these were outsiders, and were perceived as such.

The government compound was a walled compound. On the outside of it there were two ceremonial lions called foo lions. You see them in a lot of Chinese buildings today, like restaurants. They toppled those over. They stormed over the the screen. If you ever see traditional Chinese buildings or residences, a lot of times there will be a screen, or a stone wall. It is from these ideas related to feng shui that bad spirits tend to travel in a straight line, and so it would hit this wall and have to divert itself. The rioters, they ransacked over that. Then they went inside and they went’s burn the inside of the compound. They also sawed down the the Qing government mast, which is a big giant hole with the imperial ballot banner and the seal of the governor audits. They took a saw and they sawed it down.

These commoners were attacking symbols of state power, and trying to delegitimize state power in that way. What I’m trying to do in my chapter is give some of these commoners a little bit of agency, because the prevailing theory has been that the gentry control of the riot, and took advantage of the crowd’s indignation to burn all of the foreign buildings and compounds as well. But in historical writing on the riot, there’s been a tendency to say that the gentry took control of the rioters, and that’s it. But, it’s so hard to gauge what a crowd thinks or what a crowd does. In every instance in history it has its own unique circumstance, so I don’t want to generalize too much. But I think there’s a degree of agency going on on the part of the commoners or rioters.

So after they destroyed the government compound common they went the foreign compound and wreaked havoc there. Was it also destroyed?

Several buildings were destroyed, like schools, a the British counselor office. All these buildings were located on the river bank with easy access to the wharfs and ports. Most of them were destroyed or burnt. The only one that survived, as far as I know, was the Yale compound. A lot of it had to do with Yale’s reputation of benevolence. The head of the compound was a man named Edward Hume. Yale had been doing philanthropic medical work in the city to earn a good reputation. But, It’s also owing to the – I keep using this term agency, but in towns and cities in China there was this form of local government: community or neighborhood organization. They were community associations. The Association of the neighborhood that Yale’s compound was located in the center of the city. They posted a notice on the front of the gate of the Yale compound saying “We, the members of the Street Association don’t want this building to be harmed.” And it wasn’t. And I think it speaks a lot to the power of local government and the power of community. So again, there’s a lot going on. There’s a lot informing this — It’s not just people going on a frenzy. There’s some intelligence, consciousness going on. So the Yale compound was spared.

The interesting thing is that this notice was preserved by Yale. It’s archived at the Yale China association archive in Connecticut. And I found it last summer when I was doing research there. I already known about the existence of this placard, but I had no idea that it would be archived there, and I sort of stumbled across it. When I took it out of little crate was stored in, I almost fell out of my chair! It was framed, and it probably hung in the offices in Changsha for years. It may have even been framed by Edward Hume himself.

You mentioned before the existence of oral histories of the riot. And I know from our conversation before we sat down to record, that you also discovered these. So, how did you find those?

Really randomly. Someone once told me that a lot about doing history is really about showing up. In the fall of 2010 I went to Changsha on a preliminary research trip. I hadn’t lived in the city, I didn’t know anything about it really. I went there to establish contacts and started to do some preliminary work. And I was this coffee shop owned by an American, He was kind of a local history enthusiast, and he was married to a Chinese woman. And he told me, “Hey, if you’re interested in history, you might find this interesting.” And he gave me this book. It was a book about the race riot, and it was a popular history book. But what really struck me about it was that in the appendix of the book were these oral histories. As a historian I had a “Wow!” moment. None of these oral histories ever been used in English language scholarship before. And I found copies of these oral histories in other Chinese language sources.

Then I was able to get in touch with the author of the book, this woman named Tang Ying, who is a local writer, and a member of the Changsha literary association. She’s a very sweet woman, and I got to meet with her quite a bit. She actually collaborated with the man, Liu Duping, who had actually done these interviews in the 1970s. They collaborated in this book together. I ended up getting to meet him at his house toward the end of my fieldwork in 2013. He’s quite old now. That’s how I found the oral histories. When you combine that with the archival work I had done in the city, it really lends a lot to the overall project and the overall dissertation.

Which really takes these riots from a blip on the radar screen to really representing the tensions at one moment in time.

Yeah, absolutely.