What role did Texas play in the American revolution? What–Texas? It wasn’t even a state yet! And yet, Spain and its empire–including what is now the Lone Star State, did play a role in defeating the British Empire in North America. New archival work is lending light on the ways that Spain, smarting from its loss of the Floridas to Britain in the Seven Years War, backed the American colonists’ push for independence. Ben Wright of UT’s Briscoe Center for American History has been working with the Bexar archives and documents how Spain’s–and Texas’s–efforts to divert sources of food and funding to the American troops helped to tip the balance of power in North American forever.

Guests

Benjamin WrightResearcher and Writer within the UT community

Benjamin WrightResearcher and Writer within the UT community

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

In the 1770’s, Texas was part of the Spanish empire. What part of what is the United States today was also a part of the Spanish empire at the time?

We really can talk about more or less the whole western part of the continent as being part of the Spanish empire and the Spanish influence with settlements in New Mexico and California and Texas and, as well, Mexico — Coahuila state, Tamaulipas state, Mexico City. So this vast, you might say over-stretched empire really straddling North and Central America. And Texas is one of the more fledgling provinces of the Spanish empire in the 1770s.

And Spain, like France, wanted to see the British defeated in its war with the colonies. What role did Spain play in the British defeat?

A lot of revolutionary history comes back to the Seven Years War and this is no different. What we find is that the British have acquired, rather acrimoniously, what we would call Florida, Mississippi, and Alabama, but what they would call the Floridas from Spain in the Seven Years War. And what this means is, firstly, that the British Empire in North America and the West Indies is rather overstretched, more territory than can actually be held on to with the amount of manpower and military power available.

You also have Spain and France who are looking to avenge their losses, not just in North America, but actually around the globe in this race for empire in the late 18th century. The American Revolution is an opportunity for Spain, as it is for France, and a lot of scholarship talks about the role of France in the American Revolution. Spain’s vital too, partly because there are so many factors that determine the outcome of the American Revolution that we can’t discount the role Spain played as well in fighting the British along the Gulf coast, underneath where Washington and his army and Cornwallis and his army were dealing in the Southern states in the eastern seaboard.

So one of the key figures in the Texas contribution to Spain’s contribution was Bernardo de Gálvez. Who was he?

Bernardo de Gálvez was the governor of Louisiana at the time of the American Revolution. He had made a name for himself protecting Tejano communities in their communities with their conflicts with Native Americans earlier in his career. As the governor of Louisiana he is tasked by the king of Spain, King Carlos, to boot the British out of the gulf. Gálvez, with his knowledge of Tejano communities, his knowledge of the droves of longhorns, knows Texas is going to be key to feeding his mustering forces. This is particularly acute in 1779 because Louisiana is recovering from the effects of hurricanes, which have affected the amount of cattle that are in Louisiana at the time.

Why were cattle so important in the war effort in this part of the country?

It’s useful here to paraphrase Fredrick the Great, of course one of the military generals in the Seven Years War, who has this reputation as a great military strategist. One of the things he cites as one of the most important things you can do when making military progressions is making sure your army is well provisioned, as he called it, taking care of the belly. You need to feed your army, it’s one of the things that keeps your army fit in the field and it’s one of the things that keeps your army out of trouble with local populations.

So cattle make a good food source?

Well anyone whose ever had a Texas steak would find it difficult to disagree! In addition to that, you’re talking about a mobile source of food, a source of food that can more or less feed itself on the way from A to B, a source of food that really, for all practical purposes until it’s slaughtered, is refrigerated, and it’s also a multiplying source of food. One of the things Gálvez requests of the governor of Texas is that enough bulls are sent so these herds can be replenished without further droves necessitating a loss in numbers.

And what kind of challenges did Gálvez face in getting the cattle from Texas to the troops further east?

One of the problems was actually persuading the Governor of Texas to go along with this. Domingo Cabello was not a great fan of this plan and had actually made protest to his and Gálvez’s senior Teorodo de Croix, saying this isn’t really practical, this is going to lead to inflation of cattle prices, this touches on certain free trade issues that we really don’t want to get into, there’s problems in remuneration, there’s problems with communication, and not to mention that it’s actually very difficult to transfer across six, seven hundred miles, thousands of cattle, through hostile territory, native American territory. The numbers of these fledgling Texas communities are thousands of people (not tens of thousands of people). Driving large herds of cattle takes manpower. Protecting large herds of cattle takes manpower. One of Cabello’s implications is that these guys are sitting ducks for attacks, if we send this much cattle through Nacogdoches up along the trail to New Orleans.

So about how many cattle?

From what we can ascertain in the Bexar archives, in 1779 about 2,000 were sent on one drove and then at least another 9,000 over the next three or four years.

I think it’s worth taking a moment to think about how walking from San Antonio to New Orleans is tricky enough. Walking that distance with thousands of animals, herding them, this is an enterprise that is not easily accomplished. Actually these are the first organized cattle-droves out of Texas. It’s an impressive feat.

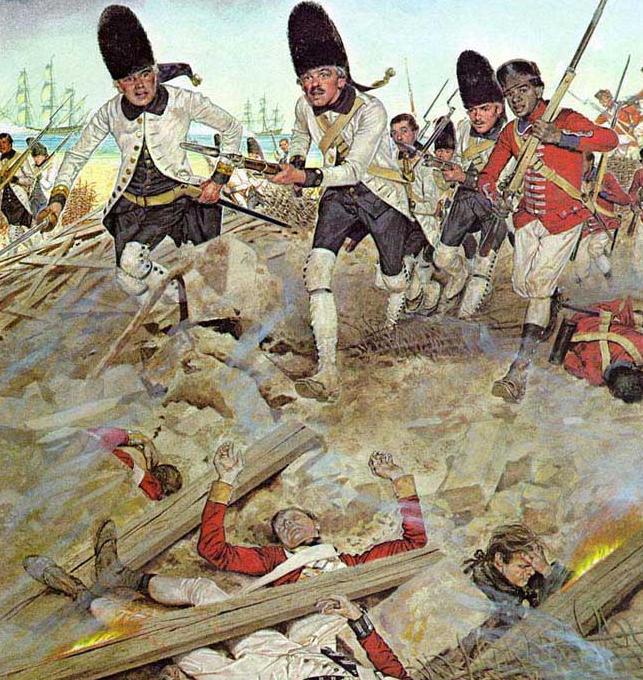

Spanish grenadiers and Havana militia pour into the ruins of Fort George at the Siege of Pensacola (1781)

In addition to cattle, and manpower to protect the cattle, what else did Tejanos contribute to the American war effort?

A few things. One of the reasons Governor Cabello is reluctant to do this is because when you take manpower on these droves, you take manpower away from the presidios and the settlements, which are also vulnerable to conflicts with Native Americans at this time. One of the contributions was the sacrifice of manpower that left Texas settlements vulnerable. There’s a really good example of this in 1780 when Cabello writes to the Comandante General, De Croix saying, “There’s been a Comanche attack on one of the drives.” He calls this disastrous and heinous.

A lot of these letters in the Bexar archives are between governors, these top Spanish elite officials, are very politely written, they very much beat around the bush in that sort of polite language that you find in a lot of elite conversations in European nations at this time. Cabello goes straight to it and says, “people are so intimidated in this province, I doubt I can find anyone, for whatever amount of money, to keep this going.” You get this very graphic picture of vulnerable communities undertaking these dangerous and difficult missions to get these cattle from A to B.

So the Spanish are contributing to the war effort against the British while at the same time they’re fighting to protect European settlers from Native Americans living there and also coming into this territory. So there’re really two wars going on at the same time?

Yes, and I think the conflict with Native peoples were endemic of early European settlement in North America. That’s no different in the Spanish provinces as it was in the English colonies.

Ok, we’ll come back to Native Americans in a second, because it complicates things here, having these two wars here at the same time. You’ve talked about cattle and you’ve talked about protecting the cattle. Did Texans contribute any funds? What else did they do?

Actually in 1780, as if the Texans weren’t doing enough, King Carlos asks all the governors in New Spain and the Spanish provinces, to collect voluntary donations to help finance Gálvez’s campaigns. According to documents in the Bexar archives, Cabello reports rather belatedly in 1784 that he’s managed to collect around 1600 pesos, and puts rather wryly in a letter to his boss he said, “I know well the delay that this assignment has suffered, but if your lordship knew the labor I’ve spent in carrying out, you would surely excuse my errors.” I don’t think he was very happy to have to go cap-in-hand to these settlements and ask, in addition to everything that was being done, for a couple of pesos for the king.

Gálvez also was active in extending the war effort and really stretching the British forces?

Yes.

By opening up a third front, is that right?

I think when we look at the military, bird’s eye view of the American revolutionary war, you’ve got forces along the ground along the eastern seaboard, French and the British Naval presences in the Atlantic, and then you also have conflicts between the British and the Spanish along the Gulf Coast states, along what is today Alabama, Mississippi, Florida. The base of these Spanish efforts in these conflicts comes from Spanish New Orleans. One of the reasons this is important is, as we’ve talked about, the British Empire at this point is overstretched. Sometimes too much success is too much of a good thing. In the Seven Years War, Britain actually takes on more territory than it can actually hold. So with the Spanish kicking the British out of the Gulf, you have a situation where George Washington ends up with a friend rather than a foe on his southern flank.

Let’s talk about the indigenous population in the territory that’s now Texas and what role they played during the American Revolution. It’s really hard to just summarize the situation, right?

Yeah, there are lots of different communities of Native Americans in North America at this time. That means there are lots of agendas. These are competing agendas, contradictory agendas. There are sort of rolling alliances and enmity between Native American communities as well as between Native American communities and European settlers. I like to think that, like other communities in the American Revolution, they too chose sides, they switched sides, they prioritized parochial concerns, they didn’t necessarily see the hand of history leading to this glorious liberal revolution that we sort of look back now with the gift of hindsight at. These were people who were concerned with the immediate concerns of their communities. We also see the Indians operated as guns for hire often, working with the British, with the French, and with the Spanish, as proxies at times, and often in mutually beneficial relationships. You see one of the typical Spanish grievances we’ve come across in the Bexar archives is the British practice of trading guns to Native communities in exchange for stolen horses from the Spanish settlements. And you see this in other parts of the continent as well, this was something everybody did.

Were there any factors that limited Indian activities at this time? It sounds like they had a lot of options.

One of the things that European settlement brought to North America were, in addition to guns, horses. So you’re at a point where Native communities are actually pretty fierce and formidable military powers. In a fledgling community like Texas, where you’ve got thousands (rather than tens of thousands), you have a much more level playing field for negotiations and things like that. At the same time though, we see this going back to Cabeza de Vaca in the 16th century, Europeans also bring disease with them. The late 18th century was no different. You see in the 1780’s, in particular, there are small pox epidemics that really decimate Indian communities.

What were some of the long lasting impacts of Texas’ role in the revolution?

The importance of Texas’s role really boils down to how you value the importance of the Spanish role. We talked about how Frederick the Great said you’ve got to feed your army, if you want to hope to have any success. Bernardo de Gálvez did have a lot of success. He successfully laid siege to British settlements like Mobile and Pensacola, effectively nullifying British power in the gulf. This means George Washington finishes the revolutionary war with a friend rather than a foe on his southern flank. How we gauge the importance of the Spanish role in comparison to the military prowess of Washington or the effect of the French naval resources has been hotly debated for centuries. One thing we can say is that Thomas Jefferson certainly thought it was a very useful contribution. One of the treasures of the Briscoe Center is this letter written by Jefferson to Bernardo de Gálvez saying, basically, Thank you so much for what you’re doing. The weight of your empire has tipped the scales and we are expecting a happy ending to this present contest.

You mentioned earlier that these were some of the first large-scale cattle drives that the Spanish vaqueros, the Spanish cowboys, carried out. Did this contribute to making Texas an economic power?

I think after the revolution Texas stagnates and even languishes, which is one of the reasons why the Spanish at a certain point agree to open Texas up to Anglo settlement as well. It got to a point where numbers were just the bottom line, let’s just get folks here. But one of the interesting connections we get with the story of the Texas vaquero, the Tejano vaquero driving cattle up to New Orleans in the revolutionary war, is the connection it gives Texas with the revolution. Often we think of the Texas connection as being Anglo settlers in the early 19th century coming from the United States and bringing these revolutionary ideas and bringing their way of doing things, what we will and won’t put up with from our government, and transplanting that to the western part of North America. Actually we see there’s an earlier connection, and it’s a connection with Spanish settlers in North America aiding the Spanish governor of Louisiana, who is an active agent in the revolutionary war. So we end up with this lovely buttress to the multi-cultural heritage of Texas and the Union.