During the explosion of African American cultural and political activity that came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance, a number of white women played significant roles. Their involvement with blacks as authors, patrons, supporters and participants challenged ideas about race and gender and proper behavior for both blacks and whites at the time.

Guest Carla Kaplan, author of Miss Anne in Harlem: White Women of the Harlem Renaissance, joins us to talk about the ways white women crossed both racial and gender lines during this period of black affirmation and political and cultural assertion.

Guests

Carla KaplanDavis Distinguished Professor of American Literature at Northeastern University

Carla KaplanDavis Distinguished Professor of American Literature at Northeastern University

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Can we begin with a brief description of what the Harlem Renaissance was?

Sure. Not everybody knows about the Harlem Renaissance, although it is one of the most famous times and places in American History because it became a moment and a place that was really famous, not just across the nation, but around the world as the nation’s first place in which black Americans could claim for themselves the identity they wanted. Harlem became famous as a Mecca, almost a holy land, for black self-definition and black self-determination. For black folks to say “we’re not going to keep responding to white ideas of who we are; we are going to define ourselves for ourselves by ourselves and as our selves.”

So really the Harlem Renaissance is a story about black self-affirmation and black cultural development and political assertion at this time of racism. It turns out there were a number of whites in New York and elsewhere in the country who supported that movement. We have a lot of histories of the white men who supported the Harlem Renaissance but it turns out that the women who were involved were overlooked. That’s what your book is about, right? Lets first ask why have they been forgotten?

I think that part of the reason they have been forgotten is the difficulty of telling a story as layered as the story of the Harlem Renaissance is. You’ve already pointed to one of the great ironies, which is that this is most famously a movement of black self-determination and self-definition, but it is also a biracial movement. There are whites involved at every level of the artistic and of the politics of this movement. So whether we are talking about little theater or small magazines or newspapers or political organizations like the NAACP, they are dedicated to black self-definition, but always they involve progressive white people. And that’s been a sort of complicated story to tell. How do you tell a story of black self-determination that is also multi-racial? It’s only fairly recently that we’ve begun to tell the story of the Harlem Renaissance as a biracial story.

And as is so often the case, the men got the attention first. And the white men of the Harlem Renaissance, publishers like Alfred Knopf, cultural impresarios like Carl van Vechten, white writers like Sherwood Anderson and H.L. Mencken got a great deal of attention for their activities, political and cultural, in Harlem. White women tended to draw less attention to themselves at the time, they often had less money in their own names to spend, and they lived during a period when it was considered unseemly and improper for women to draw public attention to themselves. Many of the white women of the Black Harlem Renaissance, even though they contributed mightily to the arts and the politics, still adhered to that dictum, that proper ladies didn’t draw much attention to themselves. Often they hid their own work under a bushel barrel, as it were. They hid their own work to not be unseemly. It’s only recently that people have begun to ask questions about them. My book is the first to say, “let’s tell the story of the white women who said ‘I want to be part of this black movement of self-determination and I want to contribute to it.’”

You point out, in your introduction to the book, that even if we understand race as a constructed category, in the 1920’s it was still a very rigid line to cross. At the same time that these women were not trying to draw attention to themselves, they challenged rigid ideas about race just by being there—is that right?

That is right. Not only was race a very difficult line to cross during this period. I want to emphasize—some people think about this period as a big, wild party where all kinds of social taboos are falling by the way side, about artistic conventions and sexual behavior and social mores (and there’s some truth in that), but this is also a period in which race lines are being drawn with much more vehemence than in most other decades that are part of the post-slavery epic. So that’s part of the background for this. There are very rigid social lines about race in the 1920s and they are different for men and women. One of the reasons we haven’t known much about these women is that they were not necessarily eager to draw a great deal of attention to themselves.

But the principle reason we have not known as much about these white women as we have about white men is that it was very, very different for white women to embrace black culture in the 1920s than it was for white men to do so. White men were actually encouraged to embrace very small doses of black culture, almost medicinally. There was a widespread notion throughout the 1920s that modern, mainstream, white, middle-class American culture was washed out, or eviscerated, or lacking in some kind of vital energy and power. And there was a very widespread idea that the idea the mainstream, male white American culture would be, by small infusions of so-called “primitive energies,” whether those were understood as Native American or African American—and they were called primitive and the movement was called Primitivism. White men were encouraged by Primitivists, and many of the modernists were also Primitivist, to expose themselves to small doses of black culture that would revitalize them.

Women however were not encouraged to do so. Women were seen as vulnerable to changing their core being if they exposed themselves to blackness to any degree. So the notion around how much exposure whites could have to blackness without changing who they were was very different for men and for women and it had a huge impact on the white women who did cross over. It’s one of the reasons we have so few of them. It also had a historical impact because they had double reasons to draw as little attention to themselves as they could. And those whose activities became known often faced violence, danger, and death threats because of what they did.

One of the women that you talk about, who had precisely this kind of attitude — she viewed black culture as being superior in some ways and necessary for revitalizing white culture — is a Texan, Josephine Cogdell Schuyler. Can you tell us a little about her and her attitudes and her fate as a white woman who became involved in black culture?

Josephine Cogdell Schuyler has emerged for many readers as their favorite person in the book, which is very interesting to me. She was a woman born to great wealth and privilege in Granbury, Texas. She was the granddaughter of Granbury’s bank founder and bank president. He also owned many, many, I don’t even know how many hundreds or thousands of heads of cattle and many, many acres. The family had a great deal of money. The house is actually still standing and it is an inn now and you can see it, which is pretty interesting. I’ve stayed there twice. She was always determined to run away from the life that she saw laid out before her in Texas. The life she was expected to lead was one in which she would marry a man of her social class and she would direct the household staff and she would do a little bit of philanthropy and arrange dinners. She said, “Uh-uh, this isn’t nearly interesting enough. I want to be an artist.”

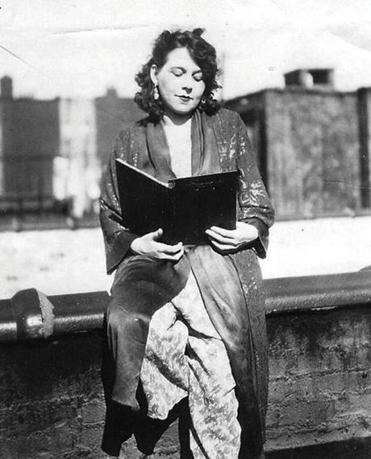

So, at sixteen, she eloped with a traveling salesman—a very failed marriage, it lasted just weeks—left him, and made her way to San Francisco where she became known as a new woman, a rebel woman, a woman breaking out of these gender constraints. She took a lover, he was a painter. She became his muse and his collaborator and his model. There are surviving nude photographs of her as a nude artist model. She lived with him for eight years and then in the late 1920s she decided to go to New York because she had heard about what was happening in Greenwich Village. She got to Greenwich Village, where all the New Women were flocking and all the modernists and the Primitivists were producing all this new artwork, and she was bored to tears. She said, “well, this stuff isn’t that interesting.” So she looked uptown to Harlem and she made her way to black Harlem.

She had been publishing some of her poetry anonymously in some of the black papers and immediately met and fell in love with the most well known black male journalist in America, whose name was George Schuyler. They married and they had a biracial daughter, Phillipa, who was a genius and a piano prodigy and helped make her parents nationally famous. Phillipa was written up in every newspaper and magazine across the nation and it gave her parents a kind of platform to disseminate their ideas about race. They believed very strongly that racial ideology was a myth. Our ideas about the so-called difference between black and white people were fictions that had been used for decades and centuries to oppress black people and to give white people unearned privileges. They fought their whole lives against that idea of racial difference, which they thought as spurious.

Some other white women who became involved in the movement were really dedicated to trying to expose some of the abuses of racial ideology. I’m thinking, in particular, about Lillian Wood. She’s especially interesting because she was white, but people assumed she was black. How did that happen?

Lillian Wood is an instance of what I like to call passing-for-black. That is to say, people assumed for decades that she was a black woman and she never corrected the record, which is different from saying I am black—I’m not sure she ever did that. Lillian Wood was a woman from Ohio who, like many Midwestern and New England women in the years after slavery, went south in the newly formed schools that were dedicated to educating a recently emancipated black population. Most white women who went to those schools, sometimes Freedman Bureau Schools, didn’t stay very long. Lillian was unusual because she stayed for four decades. She taught in a small, all black college in Tennessee. From that college in the 1920s she wrote a novel about the rise of lynching that I was talking about earlier. She wrote a novel in which she imagines, in a kind of wishful way, that federal anti-lynching law could finally be passed. One of the biggest struggles that black Americans engaged in in the 1920s was the attempt to pass federal anti-lynching laws. And year after year it came up for a vote in D.C. and year after year it was voted down. It was devastating and heartbreaking to black Americans who felt that the U.S. government and the U.S. populace didn’t really care.

Looking at all of that from Morristown, Tennessee, Lillian Wood wrote a novel about lynching, about the attempt to pass anti-lynching law, and she did a very unusual thing. She depicted in that novel a portrayal of white women as monsters. She portrayed them as complicit in the racial violence that was lynching mostly black men across the nation and she made them seem monstrous for doing so, for being complicit, for going along with it. This was so unusual. It was so unheard of in literature to see white women as complicit in racial violence that everyone assumed the novel could only have been written by a black woman. Nobody could even imagine that a white woman would portray her own sisters, so to speak, in this way. For years she was described, she was listed in bibliographies, her novel was described as written by a black woman. And she never corrected that record. I think she liked being mistaken for a black woman writer.

How did African American writers respond to the novel when they discovered that it wasn’t written by a black woman?

The people she lived with in Morristown, Tennessee, of course knew who she was and of course knew she was a white writer. They loved the novel and they were especially moved that a white woman would willingly critique other whites for their behavior. It was the kind of critique of whiteness that black folks had been waiting for for a very long time. That didn’t really come from white women until somewhat later. There was a group that formed in the 1930’s of southern white women who joined with black women to protest lynching and to protest the racial violence that was then endemic throughout the nation, but that didn’t happen till later. In her own community, she became really quite a heroine for getting white women to stand up and to say white people have to change their behavior. The novel was a minor success in Harlem, and I don’t think people knew she was a white writer. In fact, had they known she was a white writer I think the novel would have been much more successful because so few other white women were standing up to say these sorts of things. When their identities became known, as Nancy Cunard’s identity became known, a white female activist in black Harlem from Britain who was very public about what she was doing. When her identity became known, she became a local heroine in Harlem for standing up. As did a playwright named Annie Nathan Meyer who wrote an anti-lynching play called Black Souls and within Harlem became a heroine for being a white woman who crossed social lines. I actually think that if Harlem had known Lillian Wood was white it would have done her a lot of good.

On the other hand, some of the women you described were not received as well as Nancy Cunard, for example. What kinds of activities were white women involved in that were not so well received by the black activists in the Harlem Renaissance.

One of the things that I wanted to do, in bringing this untold story to light, since I was the first person to tell the story of the white women of Harlem, is I wanted to express for readers the full range of white female participation in Harlem. From what today we can still learn from as pioneering anti-racist work on the part of women like Annie Nathan Meyer and Josefine Cogdell Schuyler, and Nancy Cunard. To those women who really made critical mistakes and who always carried their own racism with them and never had much success in leaving it behind. One of those women would be Charlotte Osgood Mason who was the principle female white patroness, or philanthropist, of the Harlem Renaissance. She gave enormous amounts of money to black writers. Without her we might not know Langston Hughes and his poetry and we might not know Zora Neale Hurston and her anthropology and her novels. She was the one who funded them and many others. But she brought to that project, the funding of black geniuses, a very set notion of blacks and it was very much indebted to that movement I described, Primitivism. She locked into this idea that blacks were more alive and more essential, but that they were also more intellectually backward and they should help revitalize whites. So she’s an interesting case of someone who does a lot of good, but she does it for her own reasons and from a place we would today describe as racist. In her day she was very much appreciated for the good she did, but she was also very difficult for the blacks with whom she worked.

So some of these women were reviled, most of them and their work has been hidden and forgotten but did the Miss Annes, as a group, have an impact on ideas on race and gender?

They had an enormous impact on ideas about race and gender. This is a period not only of really rigid American ideas about race lines and really horrific American racism, but this is a period in which notions of identity are very fixed and in which people are encouraged to be one thing and stay in their box. Lots of 1920s writers reacted against that. Sinclair Lewis’ Babbitt is a famous parody of the way in which the American middle class, Midwestern, bourgeois are encouraged to be one thing and one thing only. This is a kind of notion of identity at the time. And what the Miss Annes say is, “we don’t want to be stuck in a box, we want to be even the thing that we seem to be nothing like.” So here white women say, “OK, not only do I want to participate in the Harlem Renaissance, but I’m black. I want to claim blackness for myself.” And that puts an extraordinary pressure on American ideas of who we are and who we can be. And it’s still a move we’re struggling with. When people say I want to be something I don’t look anything like, that’s who I identify with, that’s what I feel like, we’re not sure what to make of it. Even if we think people should be free to define their own identity. In their day, they were putting an enormous pressure on the idea that a) we should be stuck inside certain identity boxes, but b) that race is in the blood. That race is biological. They were part of an early movement that said, and now today still says — it’s called social constructionism — that race is a social idea. That we create social ideas of race to serve our own purposes, that it’s not biological, that it’s not in the blood. And these women took this idea so far that they were not only saying let us into the movement, they were saying, “we want to be counted as black.” So really an amazing thing to do in the 1920s and 30s.