In the early 20th century, an unprecedented cultural and political movement brought African-American culture and history to the forefront of the US. Named the Harlem Renaissance after the borough where it first gained traction, the movement spanned class, gender, and even race to become one of the most important cultural and political movements of the interwar era. Guest Frank Guridy joins us to discuss the multifaceted, multilayered movement that inspired a new generation of African-Americans—and other Americans—and demonstrated the importance of Black culture and its contributions to the West.

Guests

Frank A. GuridyAssociate Professor in the Department of History at Columbia University

Frank A. GuridyAssociate Professor in the Department of History at Columbia University

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Why don’t we start off with a general definition and explanation: what was the Harlem Renaissance?

The Harlem Renaissance was a cultural, political movement, which established, I think successfully, the importance and the centrality of African American and African derived culture and history to the evolution of the United States and the evolution of civilization. In retrospect, I think it successfully challenged and overturned the prevailing notion that Black people, people of African descent, had no history, had no culture. Much of those assumptions consolidated not just during slavery and after, and in the 1910’s and 20’s and into the 30’s we see this broad based movement that crossed genres of art and music and letters that basically sought to demonstrate the importance of Black culture and its contributions to the West.

So you’re talking about a movement that’s cultural and political. It’s probably hard to separate the two, but let’s start with the cultural movement. Who were the most important figures at the beginning of the movement who really kicked things off?

The cultural front, what many our scholars focus on, are the writers and the poets. Novelists like Jean Toomer, who wrote Cane, a very important novel—early, about 1923 or so. Also for me, Langston Hughes is extremely important as an early figure in terms of poetry, in terms of taking Black vernacular, culture, and speech and turning it into poetry. Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, Jessie Fauset—a lot of us focus on the writers and the poets, and indeed Harlem Renaissance is kind of standard course in many American English courses now, like at UT.

Then you’re moving into the realm beyond that, into musicians—Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson. And as important are not just the artists themselves or writers, but also those who promote them. People like Alain Locke, who was a Harvard educated PhD philosopher who takes upon himself to promote this younger generation of black writers and artists. Charles Johnson, sociologist who edited Opportunity, which was the periodical of the National Urban League. He’s an incredibly important figure. So you’ve got the artists themselves, but as important are these promotional figures, these figures that help promote the work of these mostly younger generation artists for not only a black audience, but also a cross-racial audience—white audiences within the United States, but also an international audience as well.

How would you explain how this whole new generation of artists and writers and thinkers suddenly emerged right at the turn of the century?

I would explain it by talking about a broader context of the period, namely the consolidation of Jim Crow segregation in the south, which is a major push factor in pushing African Americans to northern cities. There’s a generation of college educated African Americans in historically black institutions (Howard University, Fiske, Tuskegee, among others) and that’s producing a new class of aspiring black young people, some aspiring writers and artists as well. And then there’s massive migration of African Americans to the north and also Black Caribbeans from the Anglophone Caribbean and the Spanish Caribbean to northern cities, New York in particular. I think this combination of migration, political oppression, and then also political aspirations heightened by World War I—the sort of need to bring the notion of Democracy home—applied to black people. I think those are the factors that produced this tumultuous yet creative movement.

You’ve written about Afro-Cubans in New York and in the United States and in the Harlem Renaissance. Maybe you could talk about the international impact and influence on the Harlem Renaissance?

The international influence is great. We know about it in Europe, in France and Paris, we know about the contributions of English speaking Caribbean people to the movement as intellectuals, as artists, and as political activists. But the Spanish speaking Black diaspora element has been understudied. I think, for me, the Cuban aspect becomes very interesting—not because you have millions of Cubans of African descent migrating to the North, but because Cuban artists and intellectuals and writers and musicians brought a circuit of performers that comprised the Harlem Renaissance. These artistic networks cultivated by black institutions in the North and they’re publicizing the work of Afro-Cuban writers Nicolás Guillén, the sculptors like Teodoro Ramos Blanco. And so Cuba’s interesting in the sense that Black Cuban writers and artists are being showcased in the more prominent Harlem Renaissance periodicals.

So there’s this whole international dimension to the Harlem Renaissance that certainly I didn’t appreciate before. Are there also sites of similar movements outside of New York? Outside of Harlem, but within the United States?

For sure. This has been made very clear by a recent book called Escape From New York, a large anthology edited by historians Minkah Makalani and Davarian Baldwin. They have highlighted precisely the notion of this new “Negro movement,” that is very much part of the Harlem Renaissance, is really happening throughout the United States. Chicago is a major site of black cultural affirmation. Economic activity in the south side of Chicago, what becomes known as Bronzeville, is a major site for much of the same thing going on in Harlem: economic activity, artists, intellectuals, musicians all moving through that circuit. Los Angeles is another site in the 1920s. So I think the more we study the Harlem Renaissance the more we realize it has a broader national identity. Not as an impact from Harlem, but literally it’s happening simultaneously.

We’ve been focusing on cultural issues, but really the political is coming in now too. So could you summarize what the political movement of the Harlem Renaissance was, and then we’ll talk about some of the details?

Politics is as varied and diverse as the culture movement is. One of the more well known political movements of the Harlem Renaissance era was a movement called Garveyism, led by Marcus Garvey, of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Marcus Garvey was a Jamaican immigrant to the United States. He sails to New York and he gets involved in some Harlem, New York politics, but he basically leads what most historians call, the largest black mass movement in the history of the African diaspora because it’s really happening in Harlem, but also throughout the diaspora: Cuba, Central America, various divisions throughout the United States. Garveyism is all about crafting a new politics of a “new negro.” The African Diaspora should have their own nation, should have their own commercial enterprises, should have their own schools, very much a race-first philosophy that is very attractive to black people across class locations. That’s one of the things about Garveyism, it is very much a mass movement.

Then you have more elite, middle-class movements led by the NAACP, led by the very famous black intellectual, W.E.B. Dubois, who eloquently articulated the aspirations for racial, political, civic, and social equality in the year 1909 (but really taking off in 1920 during the Harlem Renaissance era). So you’ve got this kind of middle-class elite movement galvanizing around him and the NAACP, and you’ve got this mass movement lead by Marcus Garvey, and then you’ve got a host of other socialist and communist movements that are also agitated at the same time and often articulating similar aspirations, but also sometimes in conflict around class and the ultimate goals of these movements

Were socialism and communism popular among the members of the Harlem Renaissance?

I would say yes. A number of them are moving in and out of different socialistic, communistic organizations—some of them starting their own. A lot of these movements are lead by West Indian migrants to the US, but also African Americans. A. Phillip Randolph is very much a part of this embryotic labor-socialistic movement. He’s a very famous civil rights and labor activist for many, many decades in the 20th century. So yes, you’ve got a host of black radical movements articulating all of this stuff. This also makes up some of the material, the sort of literature of the movement. They’re producing periodicals, they’re producing essays, they’re producing all sorts of political tracts and that very much comprises the archive of what we call the Harlem Renaissance today.

So they’re all in dialogue with each other about how best to promote African Americans and African American culture and lead towards more equality?

They absolutely are in dialogue with each other and often in conflict with each other. Many of the movements were jealous of the mass appeal of Garveyism—in fact, that lead a number of black, African American, black-Caribbean activists to advocate for the overthrow and the end of Garveyism. They are very happy that Garvey meets his demise in the mid-late 1920s. So they’re in dialogue with each other, no question about it, and sometimes it erupted and opened conflict

Well that makes sense — that there have to be different ideas about how to move forward. What other kinds of tensions are there within the Harlem Renaissance?

I think the political tensions I just described are very much reflective in the promotion and the reception of Harlem Renaissance writers and artists. I think, like all artistic movements, they can’t be neatly packaged into something that has one message. I think a number of the members, including W.E.B. Dubois and more elite members, were a little anxious about the sort of ways in which writers like Langston Hughes were portraying black life. Hughes is writing poems in the speech of what he imagined the black vernacular speech. He’s talking about things that are happening in the nightclubs. There’s a poem, Beetle Street Love, in which he’s talking about black domestic violence. So he’s talking about things that are seen as the ugly side of black urban life, and rural life in some cases, and some of the African American elites were very anxious and upset about that. In 1927, Langston Hughes’ Fine Clothes of the Jew, the volume of poems, is very much negatively received by a number of black newspapers. So you’ve got this class tension running around. The politics of respectability and the need, on the one hand, to project that black people, African Americans, have art and culture; and on the other hand, they want to do it in a sanitized way that many of these artists are not interested in presenting.

So far we’ve been talking almost entirely about men, but there were some important women writers and activists, weren’t there?

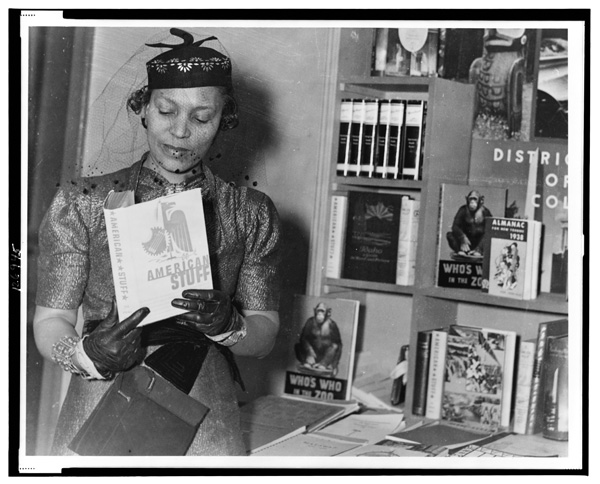

Absolutely. Among the novelists, Jessie Fauset, and scholars, including Jennifer Wilks at UT Austin, who talked about the works of Fauset and a number of other African American writers. Then there’s among the black radical activists, Grace Campbell, who was very much part of this black radical movement, galvanized by a lot of these Caribbean intellectual activists. You’ve got Erin McDuffie’s new book on black radical women in the communist movement. Louise Thompson. You’ve got Zora Neale Hurston, who was a writer, anthropologist, researcher. So absolutely, I think what the more recent scholarship, over the last decade or two has really focused on not just the contribution of women, but the ways in which queer sexuality is very much part of the life of these intellectuals, but also in the scenes of the works themselves. So we have a much more rich understanding of this movement that’s beyond the male centric narrative that had dominated beforehand

And Harlem was very attractive to white intellectuals during this period as well, right?

Yes. White intellectuals, Carl van Vechten, is extremely important in the Harlem Renaissance. He’s the one who’s putting a lot of these aspiring black writers and artists in touch with some of the main presses of the time. Knopf, for example, whose publishing a number of these works of Hughes and other writers associated with the movement. Carl van Vechten is shepherding their work to them. He becomes a documentarian himself by photographing a number of these artists and writers. Then there’s the patrons. Osgood Mason, who bankrolled a number of these artists and writers and had complicated relationships with Hughes, with Hurst, and Alain Locke.

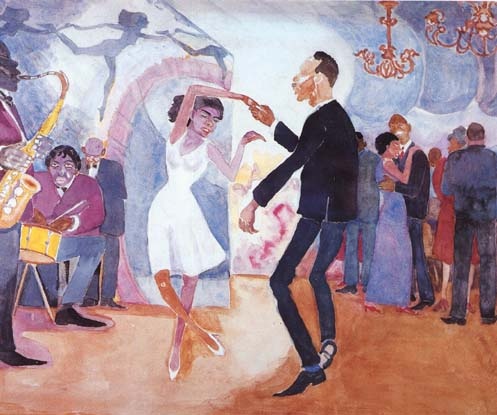

Then of course there’re the folks who were packing the Cotton Club and coming up to Harlem and seeing the Jazz and the dancers at the Savoy and the Cotton Club and others in Harlem. So there’s no question it’s a cross-racial phenomenon that, on the one hand, is emblematic of a genuine interest in black culture and black art and black writing, but also is invested in a primitivist view of black life. The idea is that they’re going there, consuming these culture products because they’re perceived as exotic and different and therefore more exciting in that way.

So a lot of whites are going up just to consume exotic black culture in the clubs in Harlem, and are also consuming a lot of the writing—political and cultural writing—do you think there was any positive impact of this new interaction between blacks and whites?

Absolutely, yes. Notwithstanding the fact that these interactions are driven by this kind of desire for the exotic, to sort of pander to white audiences that consume that kind of exotic culture, there’s no question that the movement has a tremendous impact in increasing the awareness of non-blacks to this vitality of black culture and its centrality to American and Western life. I think the van Vechtens and all the publishing houses that published these writers, the nameless people who we don’t know who went to these clubs, certainly gained a great awareness of the artistic genius of Duke Ellington, of Fletcher Henderson, and Langston Hughes. No question.

And what do you think was the impact of the Harlem Renaissance on American culture in the long term?

In the long term, I think it’s a tremendously pivotal moment in the evolution of African Americans, people of African descent, in the world as well as the United States. I think that the Oscars of a couple of days ago sort of reinforces that point. The critical acclaim that 12 Years a Slave has received, and even Django Unchained last year—those are just two small cinematic examples that demonstrate, that notwithstanding that they’re about complicated themes like slavery and oppression, that non-blacks and people around the world understand the importance and the vitality of black cultures to American western life. And that’s precisely what the new Negro movement was trying to show. So again I think that a lot of those tensions are still there, but nonetheless you have to conclude that even with its limitations, the movement, and obviously this is because there have been other black movements after the 1920s, like the Black rights movement of the 1960s and 70s among others. Hip-hop culture, which has had a tremendous impact among younger people over the past 30-40 years, is just one example, which you could link back to the Harlem Renaissance.