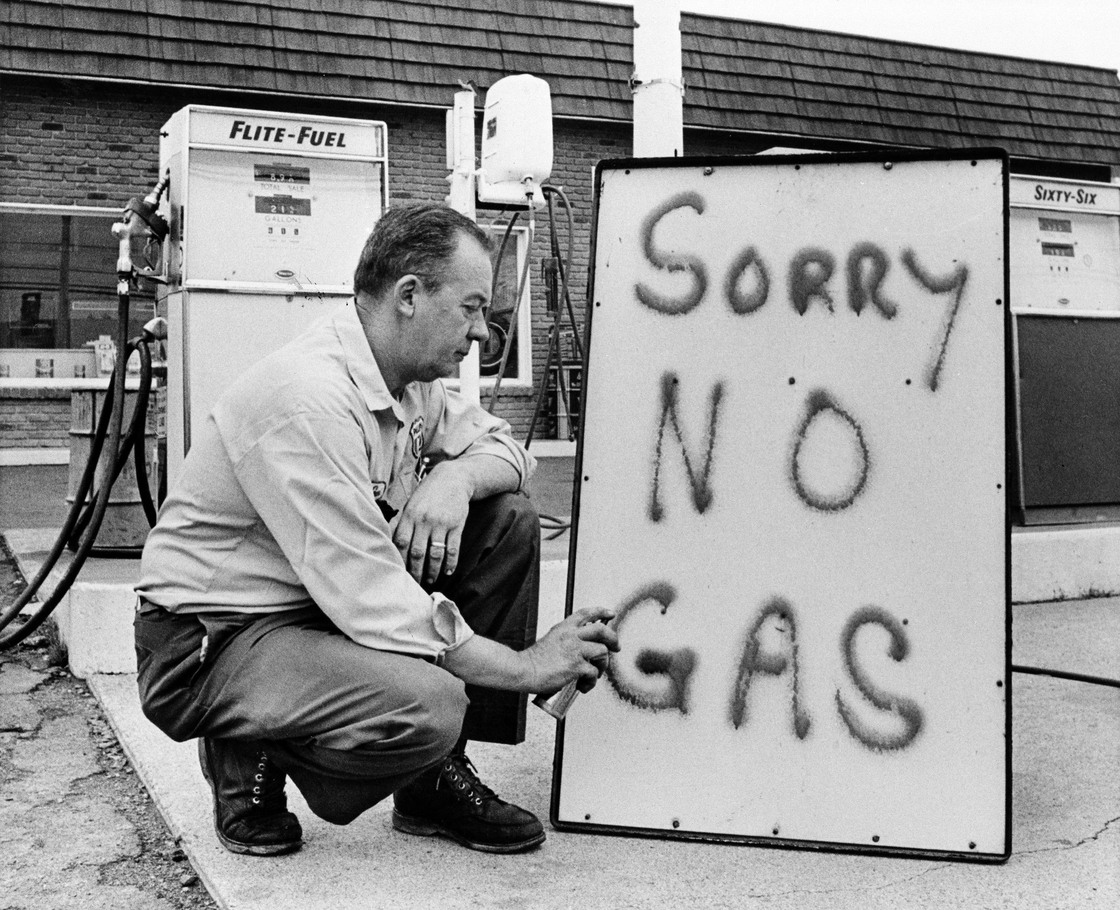

Most Americans probably associate the 1973 oil crisis with long lines at their neighborhood gas stations, but those lines were caused by a complex patchwork of international relationships and negotiations that stretched around the globe.

Guests

Christopher DietrichAssistant Professor of History, Fordham University

Christopher DietrichAssistant Professor of History, Fordham University

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Can you start off by telling us about what the energy crisis was?

Sure. To answer that question I think it’s probably best to take a quick look at three distinct but interrelated coaxial cables that run through the twentieth century and see how they all get twisted together in late 1973, in particular between October 1973 and March 1974

So the first of these cables is essentially economic, driven by the balance of supply and demand in the international economy. The second is essentially, and I say essentially because these do overlap — the politics and economics, the second is essentially political but on an international scale. And here we’re looking at the power of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries – OPEC — to manipulate supply and therefore control the price of oil.

The third cable is also essentially political but it exists on the regional level of the Middle East and it’s important here as we discuss this for the next 15 minutes or so, to differentiate between the third cable, which is shaped largely by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting countries and the first two.

Another way to think about this is to say that the Arab oil boycott of 1973 and the energy crisis are not synonyms. The Arab boycott has to do with the supply of oil to the supporters of Israel, namely the United States and Portugal, whose decrepit dictatorship, on a side note, allowed Henry Kissinger to strong-arm it into assisting in a weapons airlift to the Israeli defense forces in the middle of October.

This Arab oil boycott includes the Arab members of OPEC, so here were thinking about Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Libya, Algeria, the United Arab Emirates, but we’re not thinking of the other members of OPEC — the non-Arab members: Venezuela, Iran, Indonesia, and Nigeria.

So now that we have this context, we could locate the immediate cause of the energy crisis and this was the Yom Kippur war. So upon the first shots of that war on October 6, 1973, the Arab oil producers hastily convened at the Sheraton in Kuwait and announced the imposition of production cuts, an embargo on the US, and a price increase from $3 to $5 a barrel of oil. And this regional cable was quickly wound up with the international ones. In part because OPEC already had engaged in a series of price increases between September 1970 and September 1973. In fact, just the month before the Yom Kippur war, OPEC had already extracted an additional 70% price increase from the multinational oil corporations.

In October 1973, the non-Arab members see what the Arab members are doing and they think this is a good idea and so they also increase prices. And they do so intermittently until agreeing in January of 1974 to freeze the price of oil per barrel at $11.65. So the energy crisis in short is the fact that in course of just three months the global price of oil had more than quadrupled.

This is also a period when the energy crisis helped spur, in some ways, the environmental movement too, right, as people began to realize that consumption of fuel was limited and it was going to be necessary to take better care of the planet, a subject that is still contentious today?

And that works in different directions, interestingly. You do have this increased sense of conservation — the idea of fossil fuels as nonrenewable resources are terms that become more popular. But you also have this drive on the part of energy companies to find new sources of oil that aren’t owned by the OPEC nations. So you have drilling in Prudhoe Bay in Alaska, in the Gulf of Mexico; you have the Athabasca tar sands in Canada; you have oil from the North Sea come on line, all of which the environmental moment is not really that on board with.

Let’s turn to some of the diplomatic issues. So the conflict started in the Middle East when Middle Eastern OPEC nations realized they had a weapon in oil, a source of leverage. Tell us something about the diplomacy of oil prices.

First off we need to distinguish between Middle Eastern oil producers and the Arab oil producers because at this point Iran and Israel are still allies in the Middle East and Iran actually supplies Israel with almost all of its oil until the 1979 revolution.

There are a lot of different strains of diplomacy here so I’ll just center in on a couple that look first at the Arabs and then at the broader diplomacy of oil prices. The Arab oil weapon is actually really useful in some ways. The goal here was to change different nations’ position on the Israel-Palestine problem. In October 1973, fear of the so-called the Arab oil weapon does affect the diplomacy of American allies, and formally Israeli allies, in Europe and Asia. France, to avoid being subjected to the same type of supply cuts that the U.S. was subjected to, France sells weapons to Libya and Saudi Arabia, which they know are being transferred to Egypt. Great Britain ships arms to the Arabs and actually leaves contractual obligations to Israel unfulfilled. And Japan and the European community do similar things but in the realm of public diplomacy, calling on Israel to withdraw to its pre-1967 borders.

As a result, these nations are excluded from the boycott. But of course no one could really be immune to the price increases and on a deeper level the diplomacy of the price increases is connected to the rise of energy consumption in the West because this energy intensive lifestyle was understood as central to the success of liberal capitalism. The oil companies, of course, themselves promoted this. They thought they had essentially an endless supply of oil. But at the same time the OPEC nations, beginning in 1960, are waging a campaign to try to wrest pricing and production control from the grip of the so-called Seven Sisters, the multinational oil companies. And that’s part of a broader Third World issue that has to do with the history of imperialism, of an unjust oppressive past…

Of the colonial past…

Yeah, the colonial past. And this was a political issue that united a lot of people that really hated each other, for example, Iran and Iraq. Throughout the war in Iran and Iraq from 1980 to 1988, in which I think one and a quarter million people were killed, representatives of both governments not only continued to go to OPEC meetings, but they even sat next to each others because of alphabetical order.

So how was Israel involved as all this?

In October 1973, mostly as a catalyst, as a participant in this war. But there are historians who have looked at the longer links between the Arab-Israeli conflict and oil in the Middle East. As you know, conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors began even be the new state of Israel was formed in May of 1948. That conflict had taken overt war form a number of times: in 1948, during the 1956 Suez crisis, and also in the brief but highly significant 6 Day War in June 1967. And that war, which resulted in humiliating defeat for the Arab frontline states and led to the Israeli occupation of substantial Arab territory, was also important for the link between the question of Palestine and oil.

Essentially what happened is after the 6 Day War the Arab heads of state got together in Khartoum and they agreed that the oil producers –- in this period that was Saudi Arabia, Libya, Kuwait and Iraq — it was agreed that they would bankroll Palestinian resistance to Israeli occupation. And this is role, this use of oil money for the Palestinian cause is a role that will have great endurance.

How does the United States respond to the rise in oil prices and the assumption of power that the OPEC nations took during this period–what did the U.S. do?

If you read Henry Kissinger’s memoirs (and Kissinger by this point is the Secretary of State), you get the idea that he had everything under control from the word go, in October of 1973. But if you look at the documents (and just as an aside here, the papers that Kissinger illegally took from the State Department when he left in 1977, are still under lock and key and not available to historians), but if you look at those documents or what we think are similar documents that have been declassified, there’s a much shakier story that emerges. In short, what Kissinger does is he uses his sort of totemic, celebrity status as the world’s great statesman, to demonize OPEC, not the Arab oil producers, just OPEC in general, he paints with a broad brush, as an illiberal bogeyman that is against the proper functioning of the free market and he also makes a parallel argument that the free market was the only system that was capable of meeting the global economic challenge of expensive oil. And this is really interesting because this argument that the high prices were artificial, that they were political decisions that didn’t have economic viability, plays into the sense of vulnerability that I was mentioning earlier. And you have actual government officials fear mongering in epic or even cosmic proportions. At one point Kissinger accuses OPEC of holding the industrialized world in “strangulation,” which I’m not even sure is a word. But my favorite example is Gerald Ford’s bi-centennial State of Union address, where he compares energy independence, this plan that he’s picked up from Nixon, to independence from Great Britain. It’s that important.

OK, so what happens? How did the western oil companies reclaim control over pricing and what are the longer-term effects of the oil crisis?

Well the western companies never really regain control of pricing. In the same time period, the OPEC nations have been nationalizing, some partially through what’s called participation and some outright, the actual production facilities in the oil fields in those nations. The western companies stay on as service providers.

They really benefit from high oil prices, as you can imagine. They just pass most of the cost on to the consumer. Their profit margins are at record levels in the mid 1970s, so much so that they are accused by a number senators as being “OPEC tax collectors.”

But if this application of sovereignty was profitable for the OPEC nations, it was only that way until mid 1980s because in a certain way OPEC was a victim of its own success. As the prices went up, it made it more profitable for the Seven Sisters, the big multinational companies, as well as smaller companies to begin to develop what the industry called traditional alternatives. And these are the sources I was talking about a little earlier that were previously considered uneconomic – the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea, Alaska, the tar sands.

And by 1982, -83, -84, non-OPEC producers have put enough oil on line that prices begin to go down. Supply and demand line up and again prices begin to be pushed down. This causes a lot of damage for the OPEC nations, who have planned their fiscal spending with certain prices in mind. But most of the damage is done not to the OPEC nor to the western industrialized nations but to the poorest nations who were powerless in the face of high oil prices and the financial corollary of those high oil prices, which are huge balance of payments deficits and eventually sovereign debt. So the poorest nations in this period are rechristened the NOPECS.

And who are they?

This is the great number of less developed nations in the world. The number is probably over 130. They’re categorized in different ways by different groups, but mostly they’re called the “poor nations,” the “hardest hit” or the NO-PECs and in the wake of the Ford administration’s emphasis on the free market, what I call neo-liberal diplomacy, the funding to cover their balance of payments problems, that development funding takes the form of private loans from banks on Wall Street, the City of London, offshore banks. By the late 1970s, analysts at the International Monetary Fund are arguing that this exposure to commercial credit is going to have a drastic negative effect on their development and is really going to increase the likelihood of sovereign defaults, which isn’t something that the international financial system had ever really dealt with. It actually comes true in 1982 when Mexico, one of these new oil producers that had taken out a lot of loans to increase their production based on idea that prices were stay up, when their financial house of cards falls in, they default on something like $75 billion of debt and it causes a spiraling banking crisis across the world.

So who are the winners of the OPEC oil crisis?

That’s a really good question.

I want to say nobody, but I would say the oil companies themselves probably make out the best. Their profits are just through the roof afterwards. And they’re able to use their advanced technological skill to gain access to other sources that were not available before.

Some of the OPEC nations, of course, make out very well but that depends on which nations. The nations with larger populations that spent more of their money on development programs don’t do as well as the smaller Arab nations like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, or the Emirates.

One last question: oil prices have gone way up in the last decade and a half. Is that connected in any way to the diplomatic and political and economic issues that we’ve been talking about or is this a whole new environment?

I think yes and no.

It’s connected because the actors are the same and a lot of them have memories of this and some of them even share the same politics as actors in the 1970s. Think about Hugo Chavez before he died and his use of oil as a political weapon to both reward and punish and that did have an effect on oil prices. But now, as I understand it, Saudi Arabia is the real swing producer. They were in the 1970s as well but then they weren’t at full production capacity and now I think they’re at full production capacity.