Fears that the U.S. is being invaded by illegal aliens, of vast numbers waiting to stream across the border and undermine the American working class may seem ripped from the today’s headlines today, but a century and a half ago politicians weren’t looking south toward Mexico when debating immigration policies, they were looking west, toward China. Concerns over Chinese immigration shaped U.S. immigration policies in ways we still observe today.

Guest Madeline Y Hsu from UT’s Center for Asian-American Studies discusses the tumultuous experience of Chinese immigration to the U.S., the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, and sheds light on the lingering immigration issues first discussed in the 19th century that continue to concern us in contemporary political debates.

Guests

Madeline Y. HsuProfessor in the Department of History and Director of the Center for Asian-American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin

Madeline Y. HsuProfessor in the Department of History and Director of the Center for Asian-American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

When and how did Chinese immigration to the United States begin? I know that a lot of people might associate it with the gold rush in California in the mid-19th century — is that about the right time frame?

The gold rush was the reason for a big increase in Chinese migration to the United States; Chinese will become more visible, particularly on the west coast, after the mid-19th century, and will be used extensively as manual labor on the railroad and west coast agriculture. But, Chinese start trickling into the United States really with the Clipper trade out of Boston. Some Chinese will also come to the United States as students, brought in by missionaries. We know that there were a few Chinese that showed up in displays of exotic persons put by people such as P.T. Barnum. But, it’s really after the gold rush that we have Chinese coming in visible, and in significant numbers.

What social and economic challenges did Chinese immigrants face upon their arrival? Did they come in legally, or illegally, and what kind of challenges did they face as a result?

When Chinese first started arriving to work in the United States–and, if we think of the United States as a land of opportunity, we have to remember that this was true as well for Chinese–many Chinese looked to the west coast as a place where there were many employment opportunities. At this point in time, the United States had not yet started trying to restrict immigration and so, the United States really was a land of immigrants–so, the Chinese come.

Up until completion of the transcontinental railroad, it was actually quicker to travel from places like Hong Kong to San Francisco; you could catch a ship across the Pacific Ocean–it would take several weeks–than it was to travel from the east coast of the United States over to the west coast. So, when we think about pioneers and people helping to construct economies, Chinese were really critical on the west coast, and particularly California. We mostly associate the Chinese with the railroads, but they were also active in many, many industries such as cigar manufacturing, boots and shoes, textiles; they were really critical for laying the agricultural foundations in California. They diked certain rivers. They turned certain swamp lands into farmland. Chinese had a really critical role on the west coast.

It was also California that starts feeling the strains of having what was regarded of having an alien population. As early as 1855, Californians concerned about the Chinese start wanting to pass laws starting to restrict the numbers of Chinese entering into the state. The California state legislature did pass laws, and these were struck down in court because, according to the Constitution, it’s only the federal government that has the power to restrict immigration. California will be home to the greatest numbers of Chinese for many decades to come, and what is California’s problem will have to become a national issue, and this happened over the course of the 1870s.

There are a variety of reasons: in the 1870s, the United States is going through a severe economic contraction. Politics at the time mean that the Democrats and the Republicans are running neck in neck in presidential elections, which means that, for a swing state like California, their concerns and issues become aggrandized. Across the last half of the 1870s, both Democrats and Republicans jump onto this bandwagon of the anti-Chinese movement.

We have to bear this in mind because it reflects a significant shift in the direction of the United States. The Chinese Exclusion law that will be passed in 1882 will be the first time that the United States enacts an enforced immigration restriction law. It sets the country on a course of distinguishing people on the basis of their immigration status, and allotting differential rights. This is a considerable turn in a country that has considered itself democratic, has had embedded in its Constitution notions of equality for all, to embark on this path.

The Chinese Exclusion Law is notable also for the fact that it distinguishes Chinese as a race. This has to do with the reasons why Chinese could be seen as such a threat, such a problem that you would enact this kind of restriction.

What kind of threat were they considered?

Fundamentally, an economic threat. So, unfair labor competition. Chinese were seen as undercutting the white working class: they could live more cheaply, they could eat more cheaply in part because they didn’t know any better. They also didn’t have their families in the United States, so they could live more cheaply. There was also great fear of the Chinese numbers and the idea was that Chinese could overwhelm the west coast of the United States because there were so many of them back in China just waiting to come across the ocean.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad–which would have taken much longer if it had not been for Chinese workers; the Central Pacific railroad, which was constructing the railroad from the west coast eastward, about 70-80% of its workforce were Chinese–once the railroad was completed, it reduced travel time from the east coast of the United States to the West Coast by weeks, which facilitated Euro-Americans moving westward, but it also led to this fear that Chinese could use the railroad and travel eastward.

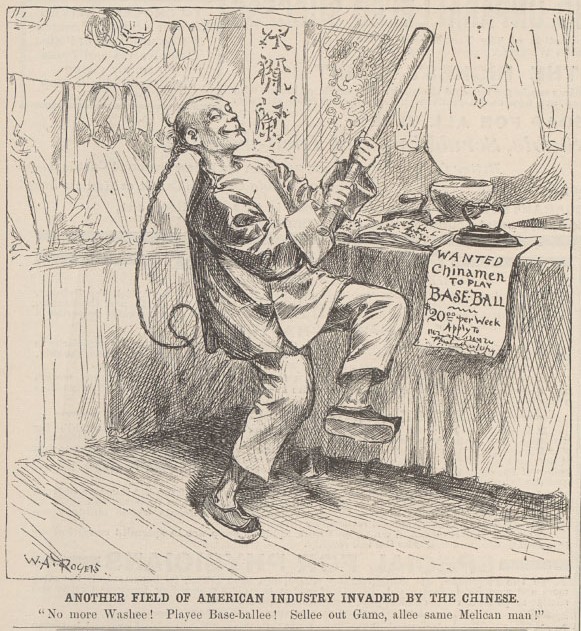

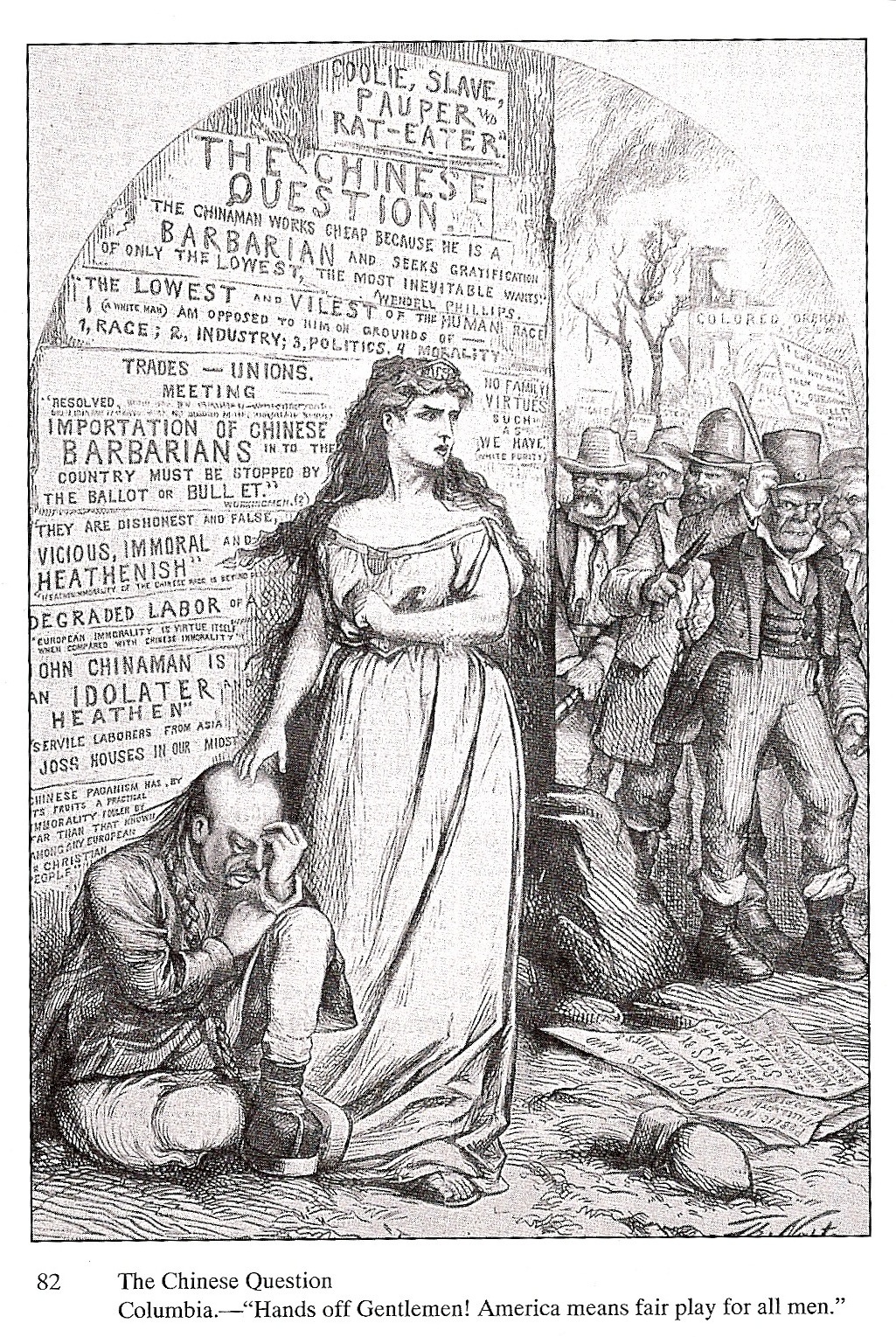

This idea of Chinese invasion–and you can look at some of the political cartoons from that time period–in fact were being broadcast widely in journals such as Harper’s Weekly, which were widely read. So, there was this idea of invasion, of competition; there also was this very powerful conception of racial difference.

We have to remember at this time period that Charles Darwin had published his famous book, and many people’s about racial difference were affirmed scientifically by what they understood of evolution and social Darwinism. Ideas of racial difference, competition between the species, the ideas that some species evolve and survive, whereas others were meant to go extinct, were in fact very real. When you couch this sense of competition against Chinese who were seen as fundamentally racially different, incapable of exercising citizenship on fully equal terms in an American republic and an American democracy–also, legally restricted from gaining citizenship by naturalization. In 1790, Congress had visited this issue and had decided that only, “free white persons” could get naturalization, mean that legally, Chinese were believed not suitable to become U.S. citizens and casting a vote.

All of these notions of differentiation raise the question of whether Chinese should be allowed to continue coming to the United States. And, resoundingly, when Congress went to vote, the answer was no. It was a matter of protecting the United States as well as conserving an idea of the United States as a nation, as well as what kinds of people can be U.S. citizens.

So, is this where that notion of the “Yellow Peril” in your book title comes from?

Yes, the “Yellow Peril” is the fear of orientals, of being taken over.

So, what were the broader impacts of that Exclusion Act? I know that by the early 20th century, we had begun to impose quotas on other groups. Did that all come out of this?

In addition to the legal foundation and the ideological justification for Chinese exclusion, you have the very serious problem–which we continue to grapple with today–of how you enforce border controls. This is something we still have not worked out.

The U.S. faces this challenge of having these very long land borders with places like Canada and Mexico. And, although you can install immigration officers in places like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Portland, all a Chinese person or anyone whose entry into the United States is restricted has to do is land in either Canada or Mexico and walk across the Rio Grande, as they did.

The strategies for border control and border enforcement develop around this problem of how you actually carry out the Chinese exclusion laws. So, certain commonplace tactics emerge with Chinese. In 1892, Congress passes another law called the Geary Act, which requires that Chinese “legally present in the United States” have to carry around a certificate of residence. This requirement was intended to cut down on the illegal, illicit border crossings, and is the precursor to what we now know as the Green Card. You have to provide evidence that you have legally entered. This, of course, pertained only to Chinese.

The 1892 act also authorizes the use of deportation. So, if you are found to be present in the United States illegally, you can be sent away. This was to deal with the reality that you can’t just enact border control at the borders. The realization that many people will successfully make their way into the United States, will be living and working in the United States, and then, what do you do about those people? The solution was to send them away. There are requirements for evidence.

Not all Chinese were forbidden from entering. If you were of certain select classes, such as students, diplomats, merchants, merchants families, you were legally allowed to enter the U.S. But, you have to be able to document that you are of the correct status. And then, there is a working out of how you are able to prove that you are a merchant or diplomat or a student. The experience of trying to enact Chinese exclusion also shows us that, as specific as the laws may become, and as carefully as immigration officials may try to carry out their responsibilities, people with motivation and drive to come into the United States–usually motivated by economic reasons, sometimes for reasons of political safety, sometimes for purposes of family reunification–people can become very clever in figuring out ways of getting around the laws.

And it also sounds like the issue of whether local law enforcement should be allowed to enforce federal immigration laws by checking papers and status is also one that we’ve been grappling with for quite a long time.

Another thing that we see getting worked out with the enactment of Chinese exclusion are issues of U.S. federal government sovereignty. What are the powers of the federal government? It is determined by the courts that it is the federal government that holds the power to enact border controls. And so, historically there is long legal and judicial precedent that it should be the federal government that holds those powers. Of course, local governments often run into problems of what you do with certain populations. There is also this working out of whether the U.S. government has sovereign control to impose border restrictions against other countries, or whether or not this should be worked out by a process of treaty negotiation.

You have to remember here that when you have very discriminatory immigration laws, it’s clearly a slap in the face of this other country. The Chinese government made efforts to negotiation through treaties and through diplomatic contexts better conditions for Chinese to come to the United States. Pretty much, the U.S. government sweeps this away and imposes its own prerogatives on Chinese mobility into North America. This becomes an accepted aspect of international relations by the turn of the 20th century, and I think governments around the world that each should have the powers to control its own borders and decide who can come in and out. At the same time, there’s this balancing act of having to try not to offend those with whom you wish to be friends. So, we see this in many of the choices that Congress will go on to make in future legislation, particularly in the 1924 Immigration act, which imposes a system of differential quotas. Some countries get extremely large quotas that are never used up, particularly historical allies of the United States. Some countries get tiny token quotas, and some countries, such as Japan, get none at all.

So, when was the exclusion act repealed–I’m assuming that at some point it was–and what caused the change in attitudes toward Chinese immigration that led to that?

We have the repeal of the exclusion act coming in 1943, in the throes of World War II. The exclusion law is being used by Japan to make the argument to China–and, we actually note, the Japanese were dropping leaflets onto Chinese territory–making the argument that China and Japan should be allied on a racial basis and that China should turn against its American ally since clearly Americans did not think much of Chinese, as they had this Chinese Exclusion law in place. Chinese were the only people identified by race for immigration restriction into the United States.

Under these kinds of pressures, and it was very political–there were across the 1930s a sense of greater understanding toward Chinese, there were the novels of Pearl Buck, the movie version of The Good Earth came out and was extremely popular, Henry Luce, who was the publisher of Time-Life Magazines was friends with Chiang Kai-Shek and his wife Song Mei Ling, who were the heads of China, so there was a lot of popular media representations that depicted China more positively. But, in 1943 it really was about the need to retain China as an ally.

Repeal was also possible because Congress and, in particular, representative Walter Judd, who had been a medical missionary in China, were able to figure out symbolic changes to immigration law. What was worked out was that you could remove the stain of discrimination against Chinese, you could get rid of the Chinese Exclusion laws, and place Chinese on the same immigration basis as everybody else, and so this was a gesture toward treating Chinese equitably, but still prevent large numbers of Chinese from entering the country. You simply placed China on the same quota basis, and Chinese had a quota of 105 per year, and you would accomplish that end, and you wouldn’t have a flood of Chinese entering.

That’s 105? Not 105,000? That’s … 105 people?

105 people per year. The main thing gained by Chinese in 1943 was that they were allowed the right to citizenship by naturalization, and the first Asian group to gain that right. The 1943 repeal of the exclusion laws was really a symbolic gesture. It was received with appreciation by the Chinese government for the gesture toward treating the Chinese racially as equals, but it will be the harbinger toward greater liberalizations to come as, increasingly, use of racial and national origins as criteria become unacceptable, particularly as the United States moves into a phase where it is attempting global leadership. You cannot simply shut out large chunks of the world, particularly Asia and the emerging African nations, through your immigration laws. This produced in 1965 the more equitable system that we have.

Are there any lasting legacies of the exclusion laws that we still have in our immigration policy?

We see the legacies all around us. The focus of concern about illegal immigration has shifted from Chinese and other Asians to Mexicans and Latin Americans. The sense of crisis around being invaded, of being take over, now focuses on the great numbers that we fear will cross the southern border, but the strategies of deportation, of creating a caste of illegal aliens–what May Nai has termed “impossible subjects”–people who are present in the United States but because of the fact of their illegal entry are never permitted to normalize and become regular Americans; this is something that is very much on the table today as we try to debate terms for immigration reform and whether or not a democracy can sustain and should force a certain caste of people to remain with lesser rights. The use of the deportations is also still very much with us; great anxieties about border control; differential access to citizenship; use of documents; some people have less rights to use the American court system–all of these things were part and parcel of Chinese exclusion and they’re still being used today.