World War I ended the long-standing American policy of neutrality in foreign wars, a policy seen as dating back to the time of George Washington. What forces conspired to bring the United States into World War I, and what was the reaction at home and abroad?

Historian Jeremi Suri walks us through the events and processes that brought the United States into The Great War.

Guests

Jeremi SuriProfessor, Department of History; Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs, LBJ School of Public Affairs, the University of Texas at Austin

Jeremi SuriProfessor, Department of History; Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs, LBJ School of Public Affairs, the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

World War I begin Europe in 1914, and lasted all the way into 1917, while the US was still not involved in the war. The U.S. had a policy of neutrality. What did that mean?

American neutrality in the period from 1914-1917 was seen by Americans at the time as the standard American position going back to George Washington. Washington had famously said in his farewell address of 1796 that the United States should not have any permanent alliances, and that it should remain aloof from the wars of Europe. He was speaking at the beginning of what would become the Napoleonic wars in Europe. This was the standard American position: not to join either side.

Neutrality meant that we claimed the right to trade with anyone that we wanted; that we claimed the right to loan money to anyone who wanted it; that we should have freedom of intercourse, that is, the ability to travel, to work with, and to interact with anyone in the world that we wished to work with. And that was the position that Americans quite naturally took.

It was not even an argument in 1914.

So, then, what happened to change that and to bring an end to neutrality?

Neutrality works far better in theory than in practice, and that’s also an old story in 1914. The war of 1812 was, in fact, over the issue that the United States wanted to assert neutrality and the British said no. The British position, and that of most belligerents in Europe, was that if they were fighting another country their friends should not trade with those who are their enemies.

The British did not want the United States in 1812 trading with France, and the British did not want the United States in 1914 trading with Germany. By the same token, the Germans did not want the United States trading with Great Britain. It was made even more of a difficult issue because not only was the United States trading with all of the belligerents–for instance, selling cotton for uniforms to all of the belligerents in Europe in 1914–the United States was loaning money to all of them.

The United States had a surplus of money at that time, and people like J. P. Morgan and others made a lot of money by loaning their cash to foreign countries who paid high interest rates on it. The United States was loaning money to Great Britain and Germany and other belligerents that they were using in the war. For obvious reasons, the British did not want the United States doing that. And so, from the summer of 1914 on, the British used what they called “Orders in Council” to claim the right to stop American shipping. They controlled the seas, especially the Atlantic, and they were able to do this.

This poses a real problem to Germany. It cuts off much of American trade to Germany, and it cuts off much of American capital to Germany. By the end of 1914/beginning of 1915, the British had shifted American trade to them–it’s not American policy, but the British had made that happen in practice. The United States protested, but we could not do anything about it.

So what did Germany do?

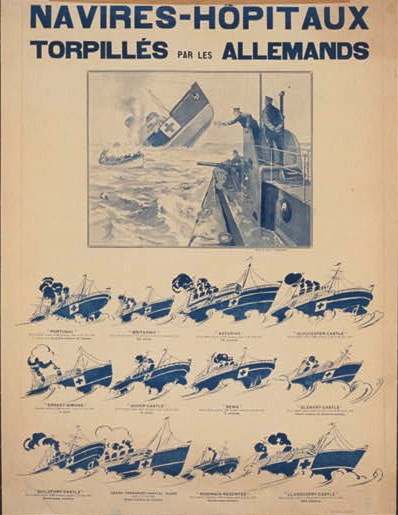

The Germans sought to break what they believed was an unfair blockade on their trade. They did not have surface ships capable of doing this, so they invested in submarines–what were called U-boats at the time (they’re really just small submarines — very small! No one would want to go in one today). What they tried to do with the submarines was destroy shipping going to Great Britain.

The German position was that if they couldn’t receive American trade, the British shouldn’t be able to do so either. The Germans believed–and they were not wrong, as they were winning the war on the ground–that they would win if the British did not have a supply of food and arms from the United States. They wanted to cut that off.

They began torpedoing American ships. There’s a particular moment when this reaches a head–May 7, 1915–which was the sinking of the Lusitania. This, for decades, was a big controversy: why was the Lusitania sunk? What was it carrying? Who was on it?

A number of historians after the fact took oral histories, asking people who were still alive from the time, and people from that generation remembered the sinking of the Lusitania in the way that people of a later generation remembered the assassination of John F. Kennedy. They remembered where they were when they heard that Kennedy was shot, and they remembered where they were when they saw the headlines about the sinking of the Lusitania.

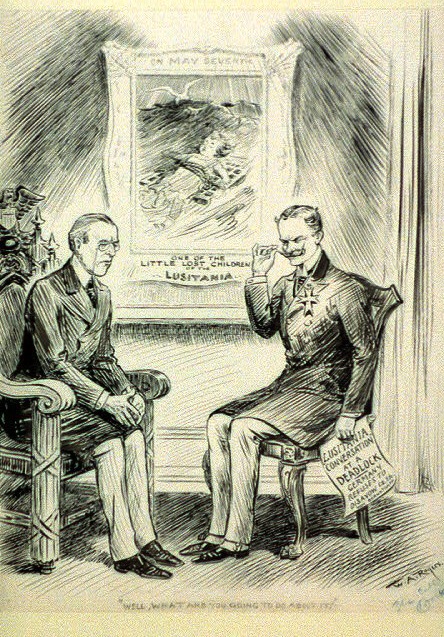

The Lusitania was an American passenger ship, and the sinking of it resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Americans. The question was: why did this happen? The Lusitania was also carrying gun cartridges as well, and so the Germans claimed that it had contraband aboard. Woodrow Wilson, then President of the United States, accused the Germans of barbarity, of violating the protections of innocent civilians. The Germans said they were just doing what the British were doing, but the Germans were killing Americans and the British were not, and that made a big difference in the situation.

But that was 1915, so there were quite a few years before we went into the war…

…absolutely! What it shows is that, despite the widespread anger–and it was widespread across party lines–Americans were still committed to staying out of the war. Woodrow Wilson still had to get re-elected in 1916, and he did not want to run as the President who had brought the United States into the war, so he ran on a peace platform: he would keep the United States out. He said that we were too proud to fight.

But, what the Lusitania‘s sinking did was turn American opinions against Germany. We shouldn’t assume that Americans would have been favorably inclined toward Britain–maybe so, but there were plenty of Germany Americans in the United States and there were plenty of people who disliked British domination of trade, its Empire, the insurance and other industries. But the sinking of the Lusitania, combined with British propaganda about it, shifted American opinion. What historians argue now is that from 1915 on, the United States is neutral, but not equally neutral. We’re showing more favoritism to Great Britain in terms of popular opinion. And that puts pressure on Woodrow Wilson.

In early 1917, the Germans increased their U-boat attacks again, and they did this because they were beginning to run out of supplies themselves–the Germans were beginning to quite literally starve. They wanted to end the war quickly, and on the ground in Europe they launched a new offensive. As part of that offensive, they tried to cut off American shipping again. And so, adding that moment to the prior moment two years ago, we have these new attacks, and Americans begin to say “we cannot tolerate this anymore.”

Famously, one newspaper said, “The only difference between war and peace now is that we are not fighting back when the Germans are attacking us.”

So what is the Zimmerman telegram? Why is that important?

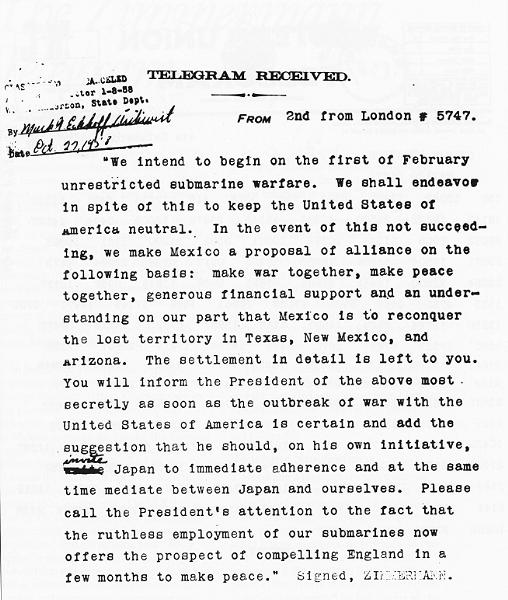

The Zimmerman telegraph is another one of these points that has long been controversial–

–among historians?

–among historians. Students always love to talk about it, too. Arthur Zimmermann, who was the German foreign minister, sends a telegram to Mexico. What he was seeking to do was put pressure on the United States — he wasn’t seeking to go to war with the United States, but he was trying to warn Wilson not to take stronger action against Germany. The telegram alludes to the possibility that if the Mexicans help the Germans, the Germans might help the Mexicans raise claims for land they lost in 1848.

Remember, this is only 60 years after the Mexican-American war, and those lands are now New Mexico, California, Arizona, and a little bit of Texas. The claim here is that the Germans will help the Mexicans try to recover this territory. The British intercept the telegram, and wait to release it. And they released it just when the submarine attacks increased again. And they used it to show the American public that the Germans really cannot be trusted. The telegram was real, but the British exaggerated what was in it for effect. And that contributes, in addition to the submarine attacks, to more anti-German feeling.

By early 1917, more and more Americans are feeling that the Germans are fighting in an uncivilized way, and that this threatens the long term interests of the United States.

So, then, what does Wilson do at that point?

This, I think, is one of the most fascinating moments in the history of the war in the United States. Woodrow Wilson is still not sure; he is deeply committed to staying out of the war, but he also comes to believe on his own terms that the world is careening out of control. The nature of war is changing, and the United States has to do something. He takes it upon himself to try to figure this out. He begins to talk about new war aims, and eventually this becomes the basis of the Fourteen Points speech that he gives, and he sits alone in the White House and tries to figure out what to do. He writes his own speech, which he delivers on April 2, 1917, to Congress. When he went to Congress, they did not know what he was going to ask for, in fact, it looks as though he could have carried Congress either way: for war or against war.

He made the case for war, and he made the argument that the world must be made safe for democracy, that the powers in the world were moving in a direction that would make democracy unsurvivable. This was his case for getting into the war on the side of Great Britain. We would not ally with Great Britain, we became an associate power. We still refused to say that we were going to fight fully on the side of the Europeans. We don’t want to defend empire, he said, we want to defeat a threatening regime, and we want to help rebuild the international system.

There was a big debate on this important point–Americans always debate war; World War II was the only exception. Every war in the history of the United States has been controversial; this one was super-controversial. A number of Senators and members of the House voted against it, many Americans protested against our entering into the war.

And what happened when we did enter the war? How does that change the course of the war?

It changes it significantly. What it meant was that the British and the French now had an almost unending of food, weapons, and people. Our soldiers were poorly trained, but they were still there and they could still fight. This demoralized the Germans, and made it clear to the German leadership that they cannot win in the west. They still push east–and, of course, the fighting in the east is even worse than in the west, but they come to conclude that they will never win in the west. They will later deny this and claim that they were stabbed in the back but … the elites in Germany clearly see that they’re going to lose the war in the west.

Before the war, the United States was in what was called the Progressive Era. How did the war change the Progressive Era?

It really brought the Progressive Era to an end. In some ways, it’s unfortunate because the Progressive Era had so many creative impulses for political reform in so many different directions–it wasn’t really Republican or Democrat in a sense. Both Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, who were political rivals, were both progressives. So many intellectuals were Progressives. Progressivism was about trying to bring the best ideas together with the best functioning government to make peoples lives better. Not big government, but better government. It was the Progressive Era that created many of the urban sanitation enterprises that we know, anti-poverty measures that combined public-private partnerships, all kinds of new education ideas: the spread of kindergarten as an almost required element for early childhood education; notions of social security and other things are actually first experimented with in states like Wisconsin.

What World War I did was pull the United States away from these progressive impulses, not because anyone decided that they were bad but because the attention turned elsewhere, it turned international. One of the tensions in American history is always between the domestic and the international. Wilson and most American energy now looked overseas, not at home, and many of these progressive impulses have to be put on hold because the U.S. government has to do two things that it hasn’t done in a long time, basically since the civil war: it has to mobilize a large army, and it has to use intellectuals and other experts to figure out how to fight the war. People quite literally who were working on education and urban reform get pulled in to working on military issues. That really brings the end of this era.

There’s also the end of the war-1918/1919–a period of terrible intolerance in the United States. Fears that Bolshevik revolutionaries and others who emerge in Europe out of the war, also emerge on the American radar screen because of what’s going on in Europe–there’s a fear that they’re coming to our country as well. And so many good patriotic Americans who were arguing for reform, they’re seen now as threatening. They’re seen as too radical. And this is the beginnings of the so-called Palmer Raid, named for Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, and the beginnings of the FBI. The FBI is created as an anti-communist, anti-radical institution in 1919.