The year 1968 was a momentous and turbulent year throughout the world: from the Prague Spring and the riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, to the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F Kennedy, to the Tet offensive and the surprise victory of Richard Nixon (possibly the most normal thing that happened all year). Apollo 8’s trip around the moon is said to have saved the year from being all bad news.

Guest Ben Wright has helped curate an exhibition on 1968 at UT’s Briscoe Center for American History called The Year the Dream Died, and discusses why 1968 looms large in our collective memory.

Guests

Benjamin WrightResearcher and Writer within the UT community

Benjamin WrightResearcher and Writer within the UT community

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

So what’s special about 1968 and the historical imagination?

I think we see a few things I think you see an absolute bombardment of the public sphere with information, particularly visual information. We see photograph after photograph. So many that we now look at and think of his iconic images of Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, election photographs, photographs of Vietnam. So, it’s very well documented and at the time that had sort of what the reporter Jules Whitford talks about as being this giant bombarding — you know, the nerve endings of Americans being stretched beyond bearing as they’re just inundated with bad news. And if you look at the calendar of the year, month after month, it’s “something else happens,” things develop, old stories take a turn for the worst -that sort of thing. But I think that experience as well is what makes it different, let’s say, from other important years in American history–the big ones, maybe 1776, 1917, 1941, 2001–is that you have this immense collective documentation of it that’s now available in archives, such as the Briscoe center, and it’s such a detailed inventory of what happened and what people thought and how people reacted. And it’s complemented by this visual record of it as well. I think when you combine those things together in an exhibit or in a program, you just you just able to recreate a very rich reconstruction of what happened.

Would it be fair to say that the fact that we have all this archival material played a role? The fact that people felt as though they were constantly being inundated with bad news, the fact that this stuff was being reported widely: television news journalism, a sort of a new kickoff thing that was going on. There is a bit of a correlation between mass media and that sort of feeling of gloom; we’re talking about it now with the social media effect…

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think social media is a good corollary to this. Because if you look at say, 2016 –which people regardless of whether they’re on the right or the left–think of as quite a stressful year where quite a lot of things happen. If you look month by month, is it that significant of a year in American history in terms of the month by month events on the ground? I would argue that the effect of social media is to magnify everything and to and to create not just an echo chamber but just a reverberation that just makes everything seem much more cavernous. And it is.

I think what people were experienced in 1968 is similar, but it’s not like cameras had just been invented or newspapers. So I think the other side of that is, yes, you’ve got an absolute critical mass of media coverage that’s now different, that now knows what it’s doing–as opposed to, say, the early 1960s. You’ve got reporters running around Vietnam embedding themselves in units and reporting back on atrocities– that’s new, right? But then you’ve also got this this unprecedented cascade of events–I mean, we’re talking — LBJ in March deciding not to run, It completely transforms the political landscape, right? You’ve got Martin Luther King’s assassination. The following month you’ve got Resurrection City. The following month then you’ve got RFK’s assassination–and we’re not in the summer yet, we’re in June. Then over the summer the Cold War kicks off in a sense, the Prague Spring is finally ended with Soviet tanks. You’ve got things going on in Paris and all across France. And, in fact, in marked contrast to the students and protesters in Chicago, in France they’re actually able to team up with the unions and you’ve got strikes across the country. So you’ve got things going globally. And I think there’s a sort of claustrophobia that that cascade of events creates, but then it it’s absolutely magnified by just how well and and efficiently things are being reported.

So walk us through the year. Set the stage for us, how does the year begin? What’s different between 1968 and 1967?

So I think the year begins as sort of ‘business as usual’ politics is partisan. Vietnam is in the back of everyone’s mind. And then the sort of first big event is at the end of January where the Tet Offensive, where North Vietnamese forces break the ceasefire and with a surprise attack and they draw the Americans into this rather bloody battle that last for several months that eventually sort of scored as a tie. But it’s because–again, bringing how things are reported, when you talk about the photographs of Dick Swanson–his archives are at the center–of the photographs of Eddie Adams–his archive too. We have that iconic image of the Saigon execution, so these these images and their reports are how this is landing in the American dining room, right on the kitchen table. And so it feels close and it saps the energy of the American public that things are going south in Vietnam.

And I think from there the next big thing that happens is in March when LBJ decides not to run again. And again, this absolutely transforms the political landscape. He’s not certain to win the nomination in Chicago, but it’s pretty hard to remove an incumbent president from your nomination. So it’s sort of, you know, that other campaigns we have going on are seen as elevating, but not necessarily endangering him having a second term. This blows the field wide open and and the person who benefits from this the most is Richard Nixon, who’s running strong on the Republican side–

–who does eventually actually win the election–

Yeah. We have–a lots been said and written about Richard Nixon’s presidency and his personality. I think says a lot about 1968 that his election is one of the most normal things that happens during the year. Let me put it in another way–Nixon has a strange allure of … he seems a calming, almost hopeful candidate. He kicks off his campaign in September with a motorcade through Chicago, which has only days before been the subject of riots, protests what goes down as a police riot, too. So, you have this absolutely chaotic scene at the Democratic Convention and then you have within weeks Nixon on a motorcade, surrounded with security, but relaxed, you know, standing up, waving, shaking people’s hands. It’s a jarring contrast. And it’s a very cleverly orchestrated one. And this is one of the things that Nixon really brings to the table in 1968 is the carefully orchestrated campaigns that breed this air of reassurance, control and even hope.

Right, because a lot of the Vietnam War had been hung on LBJ. And with the new offensive kicking off, it really looked as though things were spiraling out of control in Southeast Asia.

I think that’s definitely how it was experienced, again, in the American home, on on the kitchen table, through the newspaper, through the television, that that things are spiraling out of control. Ironically, one of the reasons for this is the fact that the Johnson administration were pretty– journalists were allowed to embed with units, they were … I’m not saying there weren’t any restrictions at all. But I think a lot of modern reporters would be quite envious of the access that the journalists during the Johnson administration in Vietnam. We think about these iconic reports that come out: Morley Safer reporting on the burning of villages. So we think of Walter Cronkite going to Vietnam coming back and saying, “Look, guys, this is isn’t going to work out.” So you know, it’s the First Amendment that sort of creates this environment of anxiety that really allows Nixon here–who famously calls to press the enemy–to really come in and say, I’m going to calm everything down, I’m going to quiet things down. Really meant Nixon was the silent majority and I think that’s an important phrase to sort of turn on its head, is that was the appeal of Nixon, that there was a majority out there that wanted some silence and that was part of the political bill of goods that he was selling.

And of course the other thing that Johnson administration was known for was the Civil Rights Act which had been passed the year before and one of its main proponents was then assassinated the following month–Martin Luther King, Jr–another shocking moment in American history.

Yes. It’s interesting to look at the photographs of King’s funeral and to just be reminded so sadly that this is a family man. This was someone who’s 39 years old who left a wife and children. There’s just a gigantic human element to the tragedy of this, which is very obvious, but, you know, we often concentrate on the the riots that ensue in Washington DC caught by Dennis Brack–his archive’s at the center; amazing photographs of looting and just outright anger on the streets. And we think of the funeral procession and we think Johnson declaring a day of mourning, and today when we think of him, we think of the statues and we think of you every every college town having an MLK Boulevard, and things like that. But you really get this moment, it’s a very human moment, it’s a very tragic moment.

I think that’s symptomatic as well about just how this affected people. The exhibit is called The Year The Dream Died. And it wasn’t just a dream that died in 1968; people died too– you know it right you see that symbolized with the to assassinations with with Martin Luther King and then with Robert Kennedy as well that there is something — you know, I’m trying not to say a way that belittles what their families went through, that they were people but they are also important symbols in American discourse. You know, if you think of MLK symbolizing a sort of racially just America that could happen; if you think about Bobby Kennedy symbolizing the return of a liberal Kennedy president, of progressive America–that sort of post World War Two dream of an America that leads itself and the world into into a progressive future. The these assassinations have this symbolic meaning that I think really lead to the anger and anime that you then see in Chicago.

Well, let’s talk about Chicago for a moment. Because this is something that comes up a lot. It’s sort of the epitome of the major nominating conference gone wrong. We can sort of compare and contrast to what happened in Chicago here with what takes place in Paris.

I think so. And you know, what’s wonderful about that comparison between Paris and Chicago is that Robert Trout, a reporter for CBS was in both at the time. He’s a foreign correspondent, he’s a legendary political reporter by the mid 1960s. And they bring him over to cover the conventions because he’s covered everyone since the mid-1930s, but he’s based in Paris and Madrid. And he sort of does these fun little radio vignettes for CBS about bullfighting and the trail of Hemingway and people bowling in Paris, and all this fun stuff. And then he finds himself in the middle of the Paris riots. And he talks in his reports about having to wear handkerchief over your nose, like you’re a Western bandit; about how tear gas makes you have a good cry, whether or not the cops were aiming at you or not, and how it smells rather like Juicy Fruit gum. And that you have to sort of smell your way home because you can realize when you’re about to enter a cloud, a tear gas, and so you have to go a different way. I mean, it was these wonderful sort of almost funny eye-rolling reports of these silly French students. And things do turn deadly. And in France several students die. They’re in pitched battles with the police throwing copper stones at them. But Trout’s reports remain sort of sort of sardonic.

Then he gets on a ship–he’s terrified of flying–So he gets on the ship and he sails to America, to New York, and then from there to Chicago where he covers, first the Republican convention, actually, down in Miami, and then ends up in Chicago for the Democrat convention. His tone completely changes. He becomes very serious, very worried about what he’s seen. He’s worried about the gas masks and the police officers, he’s worried about the the general climate of fear that seems different from France. There is sort of a sinister aspect to this, that really quite scares him, it’s not the America that he left. He talks about how the students in Paris knew what they didn’t like more than what they did like, they didn’t they didn’t have a lot of solutions, a lot of ideas for how things should move forward. Whereas the students in in Chicago we’re very clear about what they wanted: they wanted an end to the war in Vietnam. So that was an interesting contrast. But I think the other thing that you see in Chicago is the proactivity of the police–I mean this is later labeled as a police riot, where the police just descend into violence with their clubs and really injure folks.

What could possibly happen next that would add fuel to the fire? That would increase the claustrophobia and reverberation of all the political intrigue? Well, what happens is a path-breaking general election, one of those general elections that people look at again as one of the really important elections and it’s a three way contest. It’s Nixon representing the Republicans, Hubert Humphrey, vice president who’s sort of dragged his way out of Chicago with the nomination, and they’ve got George Wallace running as a third party candidate. This is going on in September. So you’ve got these three duking it out – both Nixon and Humphrey are terrified of what Wallace may do to to their prospects as a sort of third party kingmaker. Wallace does end up actually taking several southern states, but this is seen as more of an issue for Humphrey than for Nixon.

You’ve got other things going on, too. You’ve got the sentencing of Huey Newton in the Bay Area to manslaughter, you’ve got Eldridge Cleaver battling it out with the University of California Board of Regents about an appointment. Entering on the scene, sort of stage right, here comes Ronald Reagan, who was the governor of California, who very nearly had an Obama style run in the Republican convention. And you really see him being born as the political creature that you then see in the 1980s come fully into fruition. One of our archives is of a documentarian called Paul Steckler and he talks about Wallace and Reagan and how Wallace sort of acts as a way station for some of these guys that eventually migrate into from the solid South Democrat vote to the to the Reagan right. And that you see Wallace is sort of a rough around the edges proto-Reagan which is interesting–there’s obviously lots of other things going on with Wallace. But as I said, he’s an interesting guy to consider.

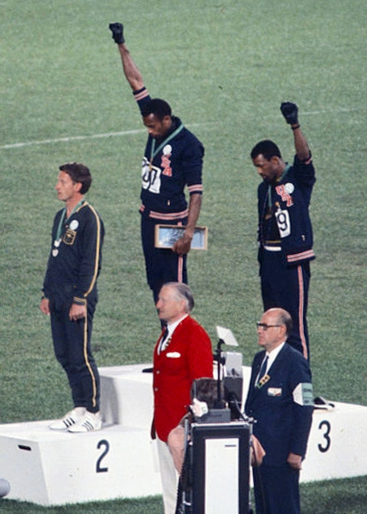

And then in October, you’ve got the Black Power salute at the Mexican Olympics, which, you know, again, creates one of the most iconic images of the year–

–and in many ways it’s sort of demonstrates a completely different approach to Martin Luther King who was nonviolent. But he was also assassinated violently, and so this sort of symbolizes the rise of a different tactic….

Yes, the Black Panthers certainly had a different approach to political change than Martin Luther King. I think sometimes that is somewhat overplayed. We have the archives at the Briscoe Center of Stephen Shames, who was the Black Panthers photographer, and he thinks there’s been a bit too much made about the militancy of the Panthers. He portrays them in his photographs–but also if you interview him– as their priority was protecting the black community, but they didn’t want to do this at the exclusion of others. That they didn’t swagger around thinking they were better. They had this what he calls a religious commitment to public service. And that if you look at the images and his collection, I think you see that more sort of just everyday mundane side of the Panthers in their community work.

But yeah, I think at the same time there, it’s something we should chew on why we have Martin Luther King Boulevard, we don’t have Malcolm X Avenue.

Exactly, exactly. So are there any bright spots to 1968? We’ve been talking an awful lot about struggle and assassination and rioting and whatnot, so something that we can remember fondly?

Well, beginning on Christmas Eve 1968 photographs and some very patchy video starts to get beamed back from Apollo 8 showing American astronauts circumnavigating another world–that is, the moon. And this is really, you know, this is the world’s first selfie. And it is sort of this sort of weirdly, hopefully existential moment where — I think it was Walter Cronkite that said “was it you know, that blue disk of ours out there in space floating alone in the darkness? how ridiculous it is that we have difficulty getting along on this little lifeboat.” It made a great impression on Cronkite, and I think Cronkite made an impression on everyone else. And actually one of the astronauts–Frank Berman is told later that they got all these telegrams and thank you notes when they get home–and one of them says, “You saved 1968!”

So you so it ends on this sort of good note. It’s what you want to happen before the credits start rolling, right? But I think there’s something else that’s interesting about this as a cultural moment as well, because obviously, six months later, you’ve got Neil Armstrong walking on the moon, but then, the same year, you’ve got David Bowie’s Space Oddity, right you’ve also got the growth of sci-fi, you’ve got 2001 A Space Odyssey you’ve got this kind of interesting intriguing thing going on where parts of the culture are starting to look out to find good news. Can we find good news outside? That’s the ironic thing about the moon, about Apollo 8, is that the only good news happens off the planet!

Well, I mean, given that we’re in such a similar cultural moment right now, where we just feel like there’s a lot of bad news and we’re looking for something hopeful. Hopefully, that aspect of 1968 will also repeat itself 50 or 51 years later.

No, I think I think what we need right now is Mars landing and that will that’ll solve all our problems.

Okay. Alright, we’ll look forward to that!