The Haitian Revolution, which took place between 1791-1804, is significant because Haiti is the only country where slave freedom was taken by force, and marks the only successful slave revolt in modern times. A ragtag force of slaves managed to unify Haiti, defeat Europe’s most powerful army and become the first country in Latin America to gain independence, second only to the United States in the Americas as a whole.

Guest Natalie Arsenault from UT’s Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies discusses the Haitian Revolution and its significance within the narrative of the political revolutions of the 18th century.

Guests

Natalie ArsenaultAssociate Director of the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Chicago

Natalie ArsenaultAssociate Director of the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Chicago

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

What is the Significance of the Haitian Revolution?

The Haitian Revolution, which took place between 1791-1804, is significant because Haiti is the only country where slave freedom was taken by force. It was the only successful slave revolt in modern times. In addition, Haiti was the first country in Latin America to gain independence, second only to the United States in the Americas as a whole. It’s important to discuss Haiti because of its significance within the narrative of the political revolutions of the 18th century.

Where does this story begin?

In 1492, Christopher Columbus “discovered” the island of Hispaniola. The island was known at the time by the Taíno Indians as Hay-ti, which meant “mountainous place.” In the 1500s, the Spaniards began to settle the eastern part of the island, where they began sugar production in 1516. They introduced slavery at about the same time; the first slave revolt in the New World happened on the island in 1522, which seems to foreshadow what would happen a few centuries later.

In the 1660s, the French began to settle in the west part of the island, and they established a colony. After a few decades of fighting, in 1697 the Spanish ceded the western part of the island to the French, who named their colony Saint-Domingue. For purposes of simplicity, we’re going to refer to the colony as “Haiti” here.

Once the French got control of Haiti [St-Domingue], what was life like in the colony?

In the early years, the population was primarily comprised of a few white planters, engagés—these were indentured servants who would work for seven years and then earn their freedom—and a small community of slaves. All of these groups were near equal in number, working together. The economy was based on small multi-crop ventures. They grew cotton, tobacco, indigo, a few subsistence crops, but they were small farms with very few slaves, and everyone working side by side.

Then sugar was introduced. 100 plantations were established between 1700 and 1704. Sugar is a labor-intensive crop, which requires more slaves. It’s also highly profitable, so more and more plantations were established, and more and more slaves were imported. Soon, large-scale crop production would dominate the landscape, and the only people you would see working the farms were the slaves.

What was life like for the slaves?

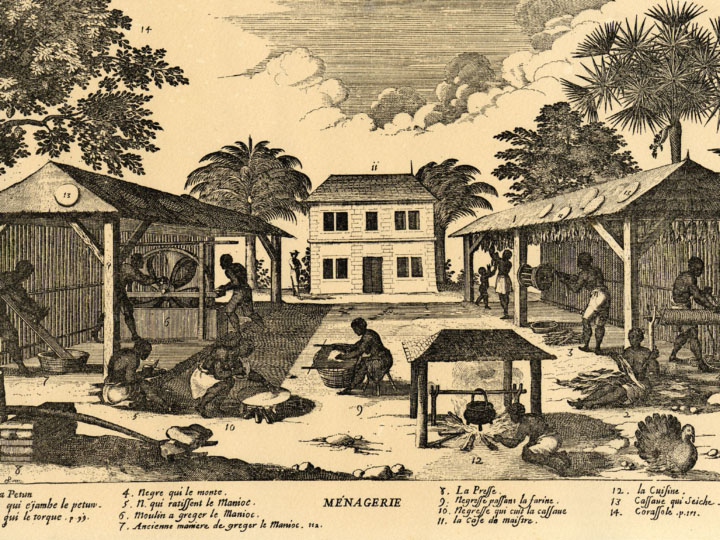

Haiti rapidly transformed from a society comprised of small farms with everyone working side by side to one in which each plantation essentially formed its own industry. There were far more Africans than Europeans, so they would separate out the slaves. Slave quarters were built on the lowest part of the property where there was no wind or ventilation, and there was excessive heat and it was very crowded. All of the slaves worked the land, men and women alike. Only the less robust—the newly arrived Africans, women in their seventh or eighth month of pregnancy, or nursing infants, and children—got the “lighter jobs.” Everyone else was working the land from five a.m. until well after dark, with working hours even longer during harvest times.

The French were particularly cruel to their slaves. King Louis issued the Code Noir in 1685 to regulate slavery and punishment, but it was never really followed in the colony. It had little influence over life there. They didn’t ration food like they were supposed to. The Code Noir required 2 1/2 pounds of manioc and either two pounds of salt beef or three pounds of fish every week, but generally most slaves only got a few potatoes and a little bit of water every day. In addition, the French employed cruel punishment techniques. If someone misbehaved—ran away and got caught—they were usually put to death in a fairly extreme fashion. The average life span of a slave in Haiti was 7 years. Essentially, the owners were OK with working their slaves to death, or punishing them with death, and buying more slaves.

Given that, what was the social and economic landscape of Haiti in the years leading up to the revolution?

In the colony, there were various groups vying for power and influence. The most powerful group was the grand blancs, or the “Big Whites.” These were the plantation owners and the elite. Then there were the petit blancs, or the “Little Whites.” These were tradespeople: shopkeepers, merchants, overseers, the former indentured servants who had gotten their freedom and now worked in smaller aspects of the economy. There was a growing population of affranchis, which were freed blacks or freed slaves, and then what were called gens de couleur, or people of color.

The gens de couleur are interesting: they were the products of white plantation owner fathers and slave mothers. What’s interesting is that they had their freedom, and they were recognized by their fathers, which we don’t frequently see in other parts of the new world, and sent by their fathers to be educated in France. Then they would come back to Haiti and own plantations and slaves of their own. The gens de couleur looked like the grand blancs, they dressed like them, and for the most part they lived like them, but there were still restrictions on the work they could do, and even on the way that they could dress.The gens de couleur had a pretty good life, but they still wanted the rights and privileges of their planter parents.

In addition to all of these groups, there were the slaves, who were by far the majority of the population. Blacks outnumbered whites fifteen times over. In 1789, there was a population of 40,000 whites and 500,000 slaves. Nearly two thirds of those slaves were African born. They still practiced traditions and religions that they brought with them from Africa, and that influenced the revolution as well.

This seems like an incredibly volatile situation to begin with. What was the spark that finally lit the fire?

It seems to have been a rather slow burning spark between 1789 and 1791. In 1789 the French Revolution began with a cry for Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. Everyone in the colony was paying attention to what was going on in France. Also, on the French side, none of the colonies were making as much money as Haiti, so they were trying to maintain control even while there was a lot of turmoil in France. There was a lot of tension between the grand blancs and the petit blancs who were vying for power and control in the colony. And then, with the beginning of the revolution, the grand blancs started seeking local autonomy. They wanted to get out of the exclusive trade agreement that they had with France and sell their sugar to the highest bidder.

The gens de couleur were seeing their chance for citizenship and equality because they couldn’t practice certain professions and had to be separate in public spaces, and they also couldn’t marry whites. They were hoping to have those freedoms. The petit blancs were eager to protect their position in the color-based class system. And all of these groups were against the slaves.

Also in 1789, there was a major drought in Haiti and a food shortage. In this kind of situation, the last priority for food distribution is the slaves, and as a result, there was a large population of slaves that was not well-fed and mistreated. In addition, in early 1791, some of the gens de couleur tried to use force to get their citizenship and equality of rights. Two representatives went to France to try to demand these rights, and when they came back to Haiti, they were beaten to death in the town square. This was a special, public punishment dealt out because the whites in Haiti didn’t want to extend full rights to the gens de couleur. So this further inflamed things.

Finally, in August 1791, the slaves organized. They held a voodoo ceremony where they called for their liberty. From that ceremony, they set out and attacked plantations, burn them down, and kill all of the white planters they came across. For months, they just went across the island burning the plantations and infrastructure.

Haiti was France’s wealthiest colony, as you mentioned, so, presumably the government in France did not react well to this uprising.

No, they did not. The unrest in Haiti moved France to send various agents there to try to quell the uprising. There’s a wonderful quote from a French colonist in 1792 that summarizes the French attitude:

There can be no agriculture in Saint-Domingue without slavery. We did not go to fetch half a million savage slaves from off the coast of Africa to bring them to the colony as French citizens.

France was not going to let this happen. They temporarily abolished slavery in parts of Haiti to deal with their own problems because they were being attacked by the British and the Spanish, who wanted into the colony as well. So, they abolished slavery for a little while so that the former slaves would fight the British and Spanish on their behalf, however they had no intention of allowing the slaves to be free.

As you mentioned at the beginning of the episode, the Haitian revolution is considered the only successful slave revolt in modern times, so we know that the slaves were able to gain the upper hand. How were they able to successfully fight off one of the world’s strongest military powers?

When the uprising started, it was basically guerilla warfare. They weren’t very organized, and they weren’t very well equipped. Within the first couple of years, Toussaint L’Ouverture arose as a leader. He was a former slave; he had been a coachman for the manager of a plantation. By the time the revolution erupted in 1791 he’d been a free man for over a decade, meaning he was able to circulate around the island and get a sense of what was going on more broadly. In 1793, he arrived on the scene, taking a leadership position. He sent a letter to slaves all over the island introducing himself. In the letter, he emphasized that he was fighting for liberty, equality, and fraternity–picking up these concepts directly from the French revolution.

He was able to start organizing armies of former slaves and defeat the Spanish and British forces that had invaded Haiti. By 1801, he’d actually conquered Santo Domingo, which was the Spanish part of the island and had made serious inroads into the French part of the island. By this point, his armies had made great strides.

Finally, in 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte decided that the rebellion in Haiti–now having dragged on for a decade–needed to be put down once and for all. His theory was that if French forces were able to capture Toussaint L’Ouverture everything else would fall apart afterward. I find this to be a really interesting perspective given the number of slaves that were rebelling at this point, that Napoleon thought that taking out one man would end the revolution. And it did not. He sent a general, who tricked Toussaint L’Ouverture, arrested him, and shipped him off to France where he eventually died in prison, but the revolution did not end. It struggled a little bit, but Napoleon’s plan ultimately failed.

In 1803, Napoleon stated:

Damn sugar, damn coffee, damn colonies!

In November 1803 slaves managed to defeat the greatest European military power. On January 1, 1804, Haiti declared its independence, and in the proclamation, they used the expression “Live free or die,” which they had taken from the American revolution.

In terms of looking at the revolution as a whole, we should consider the case of Haiti because it is important in the broader context of the American and French revolutions. They were very important predecessors to the Haitian revolution, and they were heavy influences on Haiti’s freedom fighters.