Simone de Beauvoir was one of the most important intellectuals, feminists, and writers of the 20th century. Her life and writings defied the expectations of her birth into a middle class French family, and her philosophies inspired others, including Betty Friedan. Her seminal work, The Second Sex, is a dense two volume work that can be intimidating at first glance, combining philosophy and psychology, and her own observations.

Fortunately, Judith Coffin from UT’s Department of History, is here to help contextualize and parse out the context, influences, and impact of one of the 20th century’s greatest feminist works.

Guests

Judith CoffinAssociate Professor in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Judith CoffinAssociate Professor in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

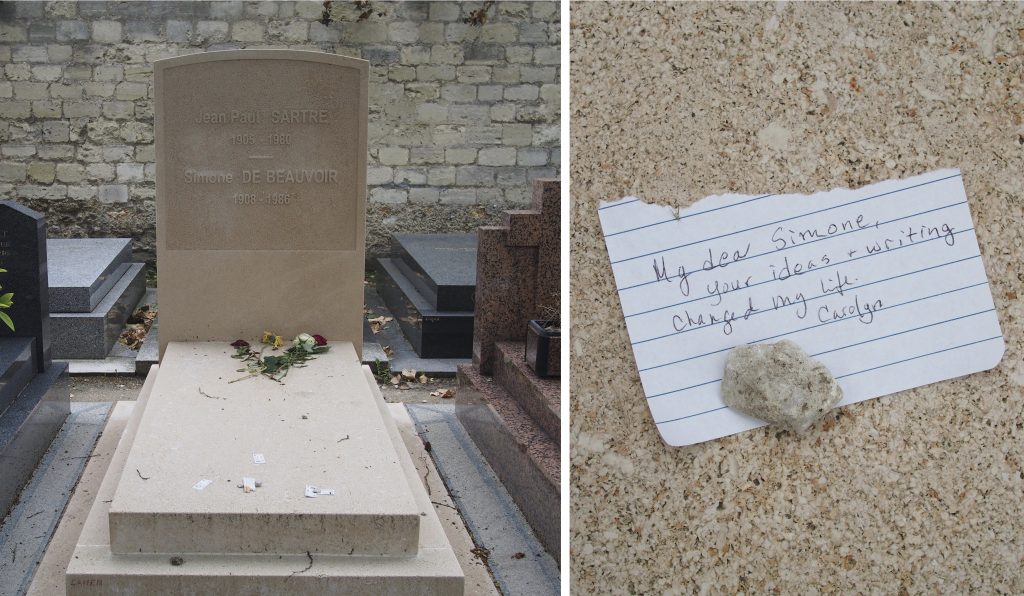

Simone de Beauvoir was an incredibly important intellectual, feminist, writer, popular subject of adoration and attack. Let’s start talking about who she was. She lived from 1908-1986 that just about covers the whole twentieth century.

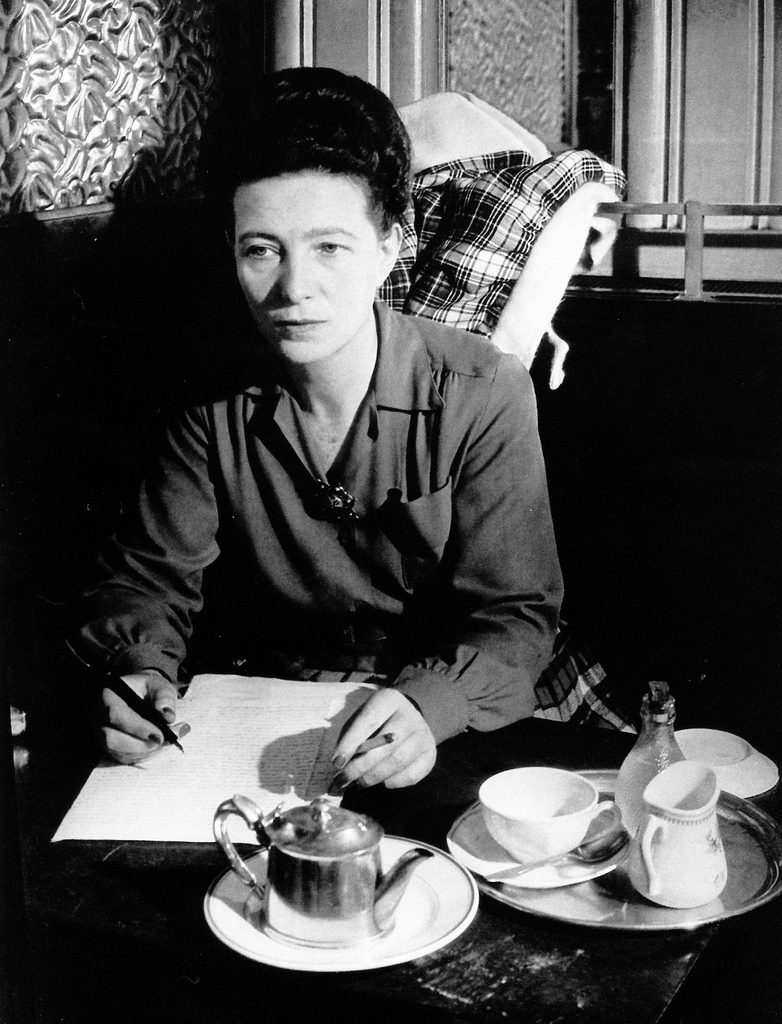

She came from a middle-class family. She was one of two girls. Girls did not have great things expected of them and she blew past everybody’s expectations. She became a philosopher and a writer. She wrote memoirs. She wrote novels. She wrote essays. She edited journals. She was linked very early to Jean-Paul Sartre, the French existentialist. And her first and most important book was The Second Sex.

How old was she when she wrote The Second Sex?

She was young. She was already well established, She had already written essays, novels. And she was in her thirties. She was looking around for a topic and in those days people liked to write memoirs and she thought, oh I’ll write a memoir. And I guess I have to think about what it meant to grow up female, to grow up as a woman. So she said, ok I’ll write about what it might be to be a woman and then I can go on to write my memoir. And that became The Second Sex. That’s the preface to her memoir. It’s a thousand pages long. It is stuffed with facts. And she wrote it really quickly. She wrote it in 18 months. You and I know what it means to write a thousand pages in 18 months or we wish we knew what it meant. And during all that time she wasn’t just an egghead. She went out. She went drinking. She went to cafes. She traveled to the US. She fell in love with an American writer. While she was in America, she said, oh ok I’ll write a book about America. So she was not only brilliant, she had a lot of stamina.

Her life is really amazing. Let’s talk about The Second Sex. When I was growing up in the 60s and 70s and that was the beginning of second wave feminism, everyone said you have to read The Second Sex and I tried to read it but it was pretty tough going. It was hard to understand what she was doing. Those 1000 pages were really stuffed. Introduce it for us.

Well, let me say that I had the same experience. Lots of names, lots of terms, Hegel, Levi-Strauss, Existentialism, phenomenology, subject, object –and all of that was in the introduction. It was not exactly introductory and it wasn’t introductory if you were growing up in the world that you and I grew up in and it is certainly not introductory for people growing up in the world now. But it was one of the most important books of the 20c. It was radical. It was scandalous. It leveled the ground in front of it, as one person said.

Lets start with some of the basic arguments. It’s two volumes. Let’s start with Volume 1.

Volume 1 starts with facts and myths. And Beauvoir starts by asking, what is a woman? Is there some essential woman-ness? And what’s cool about what she does, is that she takes the most self-evident facts of life and makes them problematic. And so she says, is a woman a uterus? You can be a uterus and not be womanly. Is woman a bunch of hormones? Are there real women? Now all of this is relatively obvious to us now, but in 1949 those terms really meant something and Beauvoir was taking these terms apart. She says the facts of biology are real but they do not have any significance in themselves. They’re only significant because we confer meaning on them.

She came to this conclusion partly by thinking hard, but also because she was part of a group of people who identified themselves as existentialists. Can you tell us what that connection is?

The philosophical basis for this way of thinking about womanhood is existentialism. And to make existentialism simple, it says that existence precedes essence. We are. We exist. That’s it. We’re free. It’s up to us to confer meaning on our life. There’s no essence of womanliness that tells how people who are born female should live their lives.

That’s pretty straightforward. It’s not very difficult these days: Beauvoir didn’t use these terms but that’s the distinction between sex and gender. And it’s a measure of how influential she is that that is now common sense. That wasn’t common sense in the middle of the 20th century.

That’s definitely true. I remember struggling with those concepts. The rest of Volume 1 is about trying to understand what femininity is then, right?

Yeah she talks about all the different people who have tried to understand femininity. What does science say? What did Freud say? What did Marx say? And then she talks about literature at great length and the myths of femininity in literature. She talks about the cult of motherhood, the cult of virginity, the “eternal feminine,” all of that stuff. And this part is very angry and polemical but it’s sort of hard to understand today because the writers she’s going after are European and French and not household names. In 1963 the American feminist, Betty Friedan, did what is sort of an update of The Second Sex and she called it The Feminine Mystique and she went after myths that were much more familiar to people. She talked about women’s magazines and popular psychology. And The Feminine Mystique is much easier to read but all of its important ideas come from The Second Sex. And in fact, Betty Friedan dedicated it to Simone de Beauvoir.

So basically Beauvoir saying that there’s no innate or essential femininity or womanness. So then she asks well, what does it matter to be a woman? What is it about women’s experience, what can we understand about women’s experience if it’s not innate?

She uses terms like woman’s “being in the world” or she uses the term “lived experience.” And those terms come from existentialism but they also come from phenomenology. And that’s her other philosophical starting point. We live in the world. We are embodied. We understand things with our bodies and our senses and not just our minds. Volume 2 is about the lived experience of women, if you will, it’s a phenomenology of womanhood. That’s a complicated way of saying it. But the thing that’s important about Volume 2 is that it opens with one of her most famous sentences: “One is not born but rather becomes a woman.” And the rest of volume 2 shows how that happens. It begins with chapters on girlhood and then adolescence and then sexual awareness and the way in which a girl’s everyday experiences of her body are profoundly different from a boy’s. Then she goes on to talk about marriage, and motherhood, almost immediately, right away, because motherhood follows upon marriage if contraception is illegal, which it was. And the point of all of these chapters is to show the existential differences between masculinity and femininity. The cost of growing up female in a world, which is not organized around women, but is organized around men. A man is human, she says, a woman is Other. A man is a subject, he goes through the world expecting to be free, expecting to live his life; she is seen as an object and encouraged to see herself as an object.

Ok that’s a lot. Maybe you could summarize the main points of the book.

Sure. Big Book. Three points. Easy!

- There is nothing innate or essential about womanliness. One is not born but becomes a woman.

- That process of becoming a woman is distorted by the fact that man is essential or a subject and woman is other. And that comes through in all kinds of ways: in culture and the family and division of labor and the organization of the household, beliefs about sexuality—all of that.

- This situation can be overcome but it is not easy. Women have to learn not to accept Otherness, not to accept “unfreedom.” There was a lot of talk in the 40s and 50s about whether or not women were happy. Beauvoir says that’s not the point. The point is whether they are free.

I hope people listening can appreciate just how radical these ideas were in the 1940s when so many of them seem like contemporary topics of discussion. Did the war, which was just over in 1945, have an influence on the way she thought about freedom and femininity and womanhood?

Oh sure, after the war, she writes all this in a Europe and a France that has been devastated by the war and so when the existentialists, Beauvoir and Sartre and Camus, talked about freedom and talked about how to recover freedom against the backdrop of this horrible experience of the war, there’s a real drama to it. We are free, we make choices, we take responsibility for our choices. One of the reasons that existentialism is so popular is that the war is the dramatic backdrop against which choices and a lot of bad choices were made. That’s important. It’s also the time when anti-colonial movements are taking shape, civil rights movements are taking shape. People are thinking about racism and anti-Semitism. So The Second Sex, which thinks about the relationship between men and women is very much a part of this conversation.

And how did people in 1949 react to The Second Sex?

Oh it was a scandal! It’s not just that I was philosophically radical, but there was all of this detail. It was quite graphic. She wrote about abortion. She wrote about lesbianism. She wrote about sexual initiation. She wrote all about sex and the body and she said those were philosophical issues. And she was a woman. And she was perfectly happy not to be womanly, not to be discreet, not to obey codes of decency. So it sold very well and there was lots of discussion, but it was also denounced.

Did her life resemble the book? Was she an object? Did she try to become a subject? Did she try to become the “hero of her own life”?

She did. And that’s one of the reasons why she becomes such an important figure. Her life really lives out the dilemmas of being free as a woman. And so she was an intellectual and a writer at a time when that really wasn’t done. She wrote a big novel about writers and intellectuals in Paris, The Mandarins, which many people did read. I remember reading that when I was young and we were all excited about the lives of European intellectuals. People still love that for reading about the atmosphere of Paris after the war: cafes, philosophical discussions, love affairs, psychoanalysis. She wasn’t married. She never had children. She wrote about all of that. She wrote about not marrying, She wrote about deciding not to have children. She wrote about her love life.

She never married but she had some famous boyfriends, right?

Oh yes. Well, the first and most important was Jean-Paul Sartre, the famous French philosopher and she made a famous non-marital pact with him. They would live their lives together they would work together and they would be together but they did not have to be faithful to each other. They just had to tell each other about all of the other affairs that they had. They didn’t quite tell all. So we only know now about some of the other stuff. But the Number 2 relationship in her life was Nelson Algren, an American writer who lived in Chicago and she fell in love with him in 1947 I believe and they had a wonderful, tumultuous, passionate love affair that lasted I think 4 years, 4 or 5 years. Traveling back and forth across the Atlantic, which was not nothing in the late 1940s. And she was in love with him, she referred to him as her husband but she refused to leave Sartre for him. So that ended sadly. And then her third major love affair was with Claude Lanzmann. Do you know who he is?

The filmmaker and director of Shoah.

He began as a journalist. He wrote for Elle magazine and Les Temps Moderne, or Modern Times which was the journal that she and Sartre edited and she began an affair with him when she was 44 and he was 27. That lasted for 7 years and that too was quite a passionate relationship. But every day she went and worked with Sartre. She sat alongside Sartre at her office, at her desk, and they wrote together. And she stayed with Sartre. She was at his bedside when he died.

Didn’t she have some romantic and sexual relationships with women as well?

Yes. And that she wasn’t quite so straightforward about. But she did and in fact one of her last relationships was with a woman. The extent to which it was romantic or sexual is very hard to tell and a lot of people debate that but I think she pretty clearly had sexual relationships with women as well as men.

Was she popular? Did people love the books?

People loved these books. She wrote The Mandarins; that won the equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize in 1954 if I’m not mistaken. And she followed that up with three big volumes of memoirs. Remember she set off to write her memoir and that became The Second Sex. That was a little bit of a detour. Her first volume of memoirs came out in 1958. That was Memoirs of the Dutiful Daughter. Growing up female and deciding not to be a dutiful daughter. The second volume was called The Prime of Life and the third was called The Force of Circumstance. And she wrote about her work, she wrote about her life with Sartre, she wrote about politics. She was involved in the campaign against the French colonialism in Algeria. She wrote and organized against torture, which was part of the French government’s campaign in Algeria. She wrote about all kinds of things: old age, about her mother’s death, about Sartre’s death, and all of these books were very, very popular.

Would you call her a feminist?

Yes. Absolutely. She’s an interesting feminist and an unconventional feminist. The Second Sex was published in 1949 and French women had just gotten the vote. French women did not get the vote until World War II. And Beauvoir opened The Second Sex saying, you know that battle is over, the battle for suffrage is over, and that wasn’t a very important battle. There are much more serious obstacles to women being free. That’s all the philosophical stuff that’s in The Second Sex. Marriage, as an institution, second-rate jobs, household chores, all of which were done by women, all of it, compulsory maternity, illegal contraception.

Both contraception and abortion were criminalized in France at this time, right?

Oh absolutely. You weren’t even allowed to speak publicly about contraception until 1967.

So she was very radical and uncompromising but she was skeptical about feminism as a movement?

That’s personal and philosophical. She wasn’t really a joiner. She was something of a loner and an iconoclast. But she also famously said, and a lot of feminists have attacked this, women do not say “we.” It was very hard for her to imagine a feminist movement that would look anything like the civil rights movement or a national liberation movement or an anti-colonial movement. She said, and this is an example of WWII vocabulary, women collaborate with men, women are complicit with men. Women are constantly invited to identify with men and to think of themselves as Other and it is too hard to get from that Otherness to a political movement. A woman, she said, has a hard time saying “I,” being a subject, and if an individual woman has a hard time saying “I” it’s very hard for women as a group to say “we.”

And how did people react to The Second Sex outside of France. We started off by talking about trying to read The Second Sex, what was her impact in general on the rise of feminism in the 60s and 70s?

I don’t think she causes any of the rise of feminism. Her autobiography was wildly popular. It made her a popular woman figure. And because she was so popular the French press republished The Second Sex in the mid-1960s and it got a whole new second life, if you will, because at that point there was a feminist movement, which wasn’t caused by Simone de Beauvoir’s ideas but came out of the civil rights movement and other movements in the 1960s and so the movement rediscovers The Second Sex and makes her into a hero. Although it also makes her very quickly into somebody they can disagree with if you have slightly different feminist positions from her. In any event, The Second Sex is so big and it has so many ideas that it had a first life in the 1940s and then a second life with her autobiography in the 1950s and then a third life as a feminist textbook in some ways in the 1960s.