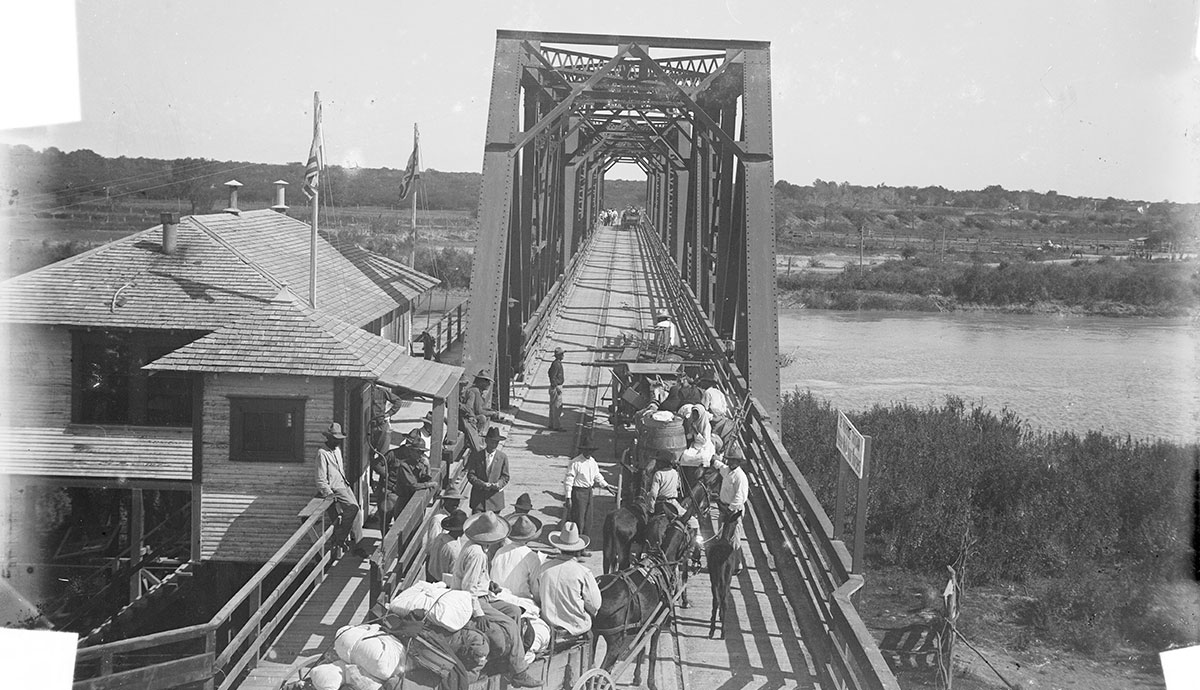

In the early part of the 20th century, Texas became more integrated into the United States with the arrival of the railroad. With easier connections to the country, its population began to shift away from reflecting its origins as a breakaway part of Mexico toward a more Anglo demographic, one less inclined to adapt to existing Texican culture and more inclined to view it through a lens of white racial superiority. Between 1915 and 1920, an undeclared war broke out that featured some of the worst racial violence in American history; an outbreak that’s become known as the Borderlands War.

Guest John Moran Gonzales from UT’s Department of English and Center for Mexican American Studies has curated an exhibition on the Borderlands War called “Life and Death on the Border, 1910-1920,” and tells us about this little known episode in Mexican-American history.

Guests

John Morán GonzálezAssociate Professor, Department of English, University of Texas at Austin

John Morán GonzálezAssociate Professor, Department of English, University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Our topic today is the Borderlands War that took place between 1915 and 1920 approximately, on the border between Texas and Mexico. Could you start with a definition or outline of what happened?

Essentially it was a period of violence, in which there was an undeclared war between the Anglo Texan and Mexican American communities, in which there was violence perpetrated by both sides, but the brunt of the violence was directed by the state and local authorities against the Mexican American population.

What made this period so violent? What was the situation at the time?

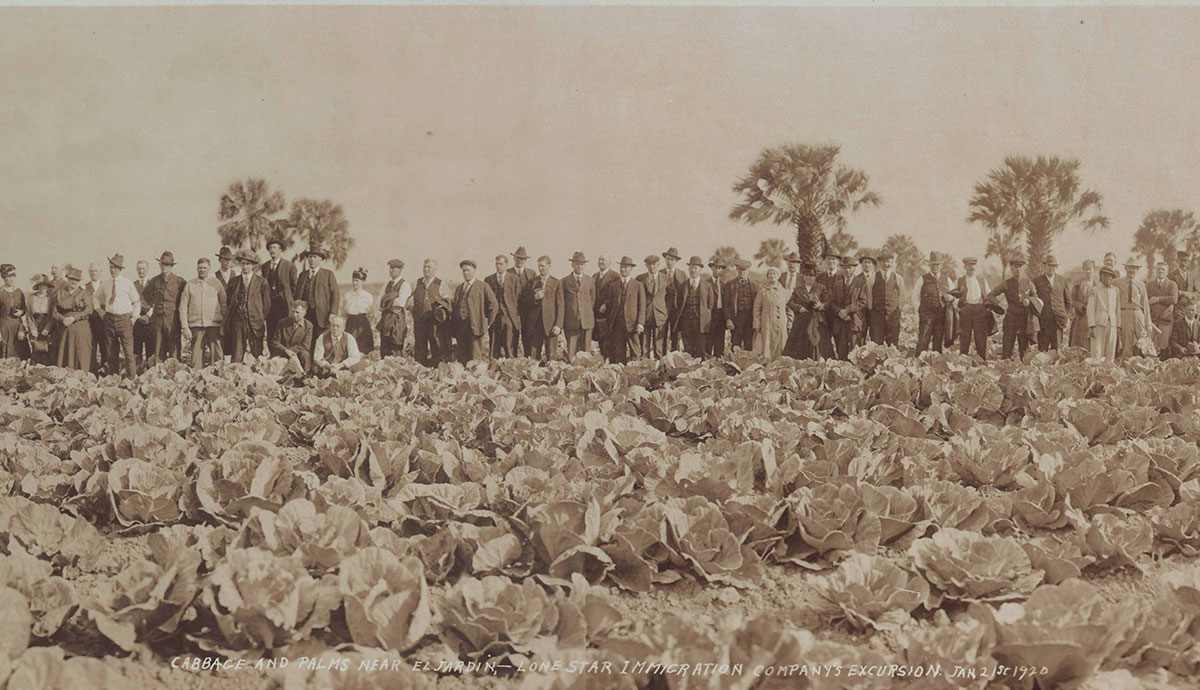

The context for this was the rapid change in the economy — a ranching economy dominated by Mexican Americans into a farming economy dominated by newcomer Anglo Texans. The rapid change over during the previous 10-20 years had resulted in a displacement of the old order, the old Mexican American order along the border, with the new Jim Crow style segregation.

Under the ranching economy, was there more cooperation, or were there fewer Anglos?

There were certainly fewer Anglos coming to the border region prior to the turn of the century, prior to the arrival of the railroad in this region in 1904. And so those Anglos who did come in tended to inter-marry into established Mexican American ranching families and became essentially Mexicanized. After that, the number of newcomers coming in with decidedly different views about Mexican racial inferiority went there to exploit cheap land and cheap labor.

Who were the main targets of the violence?

The main targets of the violence were the general Mexican American population of the area who were often perceived to be in cahoots with raiders and other guerilla fighters who were against the changes that occurred.

About how many killed during this violence?

Estimates are very hard to come by precisely because many of the incidents were

Covered up by those who perpetrated them, particularly those of law enforcement.

The estimates range from a low of 3-500 to 3-5000, which was a figure that Walter Prescott Webb, the hagiographer of the Texas rangers, came up with in his 1935 history of the rangers.

Why did the violence escalate at this point?

The violence escalated because the Mexican Americans of that region who had been displaced from their place with the society and economy of the region very much resented the new racial order imposed upon them by the Anglo newcomers.

They were disenfranchised in terms of their social status, they were disenfranchised literally in terms of their votes as white only primaries became the norm and therefore they saw their power ebbing away. So this built up a great deal of resentment with the new order.

Did the state of Texas play a role in supporting or trying to limit the violence? Were they on a particular side?

The state authorities, particularly as embodied by the Rangers, were perpetrators of some of the worst violence of this period. Extra judicial killings of Mexican Americans by the Rangers was quite common in this period, often taking the form of “shot dead attempting to flee” kind of scenarios. So the Rangers were very much part of the problem rather than an attempt to ameliorate the situation.

And certain segments of the newcomer community very much welcomed what they saw as putting the local Mexican American population in their place. There were lynchings, shootings in the back, decapitations, mutilation of bodies. There was one instance, in which bottles were inserted into the mouths of those who were executed. The violence was extreme and the kind of symbolism attached to it was equally extreme.

One Texas newspaper you quote as saying that this was a good thing because there was a serious surplus population that needed eliminating. Was that a widespread sentiment?

It was to the extent that the Mexican population was viewed as a kind of necessary evil. That is, on one hand, many newcomers came to that region of Texas expecting to be able to use a cheap labor force for their economic endeavors. On the other hand they represented a threat because of their ability to vote and hence the idea of a surplus population that needed trimming is an expression of this latter sentiment.

Can you give us some examples of some of the things that happened?

Yes, the summer of 1915, particularly the months of August through October, saw the height, the most intense violence in the region. In one instance, in late September of 1915, there was a clash between Texas Rangers and about 40 Mexican Americans in Hidalgo County, where Rangers took a dozen prisoners and promptly hung them and their bodies were left to rot for days.

In another instance that same month, Texas Ranger captain Henry Ransom shot landowners Jesus Bazan and Antonio Longoria once again leaving their bodies out in the open to rot. And at one point Ransom reported to Ranger headquarters in Austin that: “I drove all the Mexicans from three ranches.”

Did state officials just turn a blind eye to the violence in the sense that they supported it? Or were there investigations? What was the state role here?

The Rangers had received clear signals from the Governor’s office and other authorities that they had a free rein to handle or control the situation as they saw fit. That is, a clear sign that no one would be prosecuted for any extra judicial killings. The depredations only came to a stop when Brownsville State Representative José Tomás Canales initiated an investigation of the Ranger force and their actions over the previous decade in 1919.

So why would the Rangers, a force that was created to protect the residents of Texas, commit this violence against Mexican Americans?

Essentially, they were in the service of consolidating the new, white, supremacist order in south Texas. That is, essentially was the purpose of the violence was to send a clear signal that Mexican Americans would be dealt with harshly if they attempted any opposition to this new order, whether through the ballot box or other means.

Did the Mexican government play any role in what was going on?

The Mexican government did not have a direct role in this, because the country was in the middle of a revolution. There was constant instability over which faction controlled which parts of the border. It was more the climate of instability that allowed raiders to cross back and forth across the Rio Grande with impunity and created a sense of siege by the Anglo community in this part of south Texas.

Can you say anything about the raiders themselves, that is, the people who were resisting changes taking place in the economy and then eventually the violence being perpetrated on them by the Rangers and other forces?

This group is often referred to as Los Sedisasos or seditious ones and they attempted to essentially oust the new Anglo order by these guerilla raids upon ranches, the derailing of a train near Brownsville, and these sorts of actions, but they were very much constrained by the small number of raiders as well as the state’s overwhelming use of force against them.

So you said that the violence finally subsided when State Representative Canales called for an investigation of the Rangers in 1919. And that ‘s the conventional ending of the violence; did it continue after that?

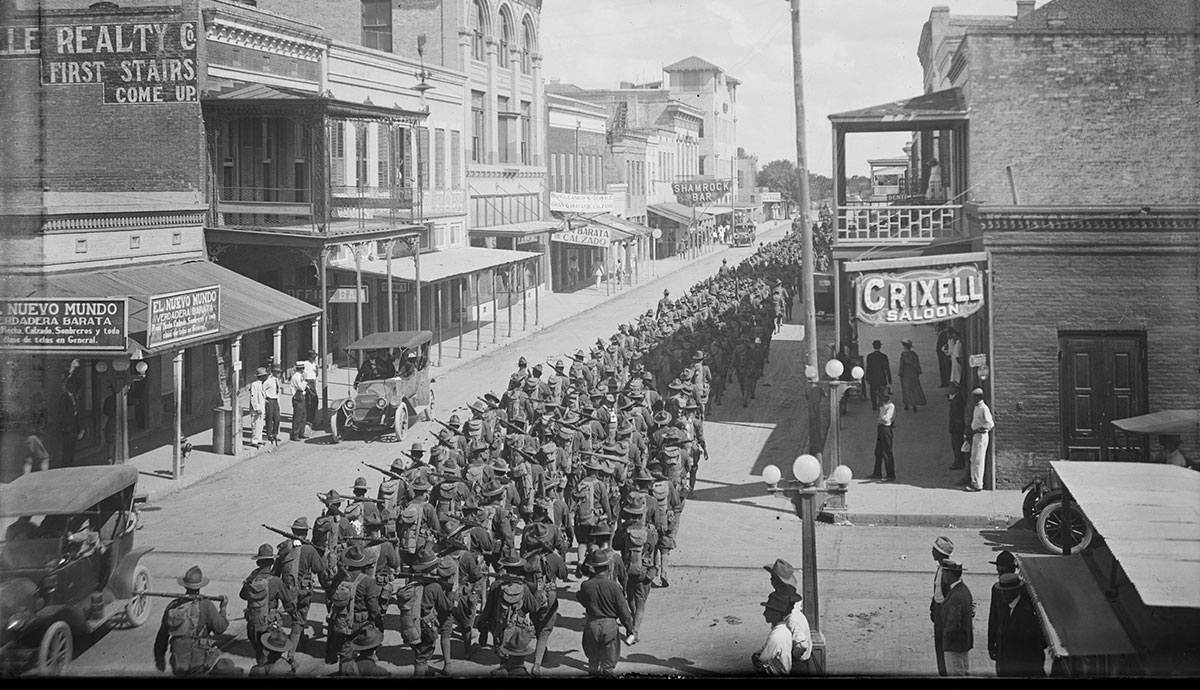

Well in fact it did. I think the most egregious episode was the Porvenir in West Texas in 1918 when Rangers executed 15 Mexican men, separated them from their families and executed them. Now I have to say the role of the U.S. army was crucial here in beginning to tamp down the extra judicial actions of the Rangers and local vigilantes.

What did they do?

Essentially they very much saw the Rangers and the local sheriffs as part of the problem, as continuing the violence rather than defusing it. Mexican Americans began to see the federal government, in the guise of the US Army, as being on their side in some respects.

So we have this very complicated picture where we have a changing economy, we have a revolution going on south of the border, we have people trying to make a living, a small group of people violently resisting the changes, and the representatives of the state of Texas trying to suppress them but also carrying out violence against people randomly as well. What was the response of other people? Was there any sort of peace movement? Was there any cooperation among newcomers, Anglos, other European settlers, and the Mexican Americans there? How did other people respond?

Yes, it was complicated picture be certainly there were Tejanos who were aiding the Rangers and other parties in the suppression of the Mexican American community and, on the other hand, there was Anglo settlers who were very much appalled at the violence perpetrated against local communities. One of them was Brownsville lawyer and historian Frank Cushman Pierce who compiled a list of 102 victims, entirely on his own time. Then he also confronted Lon C Hill who was one of the major developers of Harlingen Texas about his role in these incidents.

In supporting the Rangers, in supporting the violence?

Yes.

What then are some of the short-term consequences of this violence? It must have been incredibly disruptive.

Absolutely. The violence in the lower Rio Grande valley in particular resulted in the depopulation of rural areas as Mexican American residents fled to the relative safety of border towns or crossed into Mexico for safety. This only accelerated the transfer of land to newcomer Anglos as Mexican Americans abandoned their lands. This also had implications for Mexican Americans from this area as they were drafted into military service for the First World War. They resisted the summons to serve because they could not reconcile the violence visited upon them by the U.S. with service in the same military that they saw as part of the problem. And they were termed slackers in the language of the day for allegedly slacking off their duty as patriotic citizens. One other implication was that Walter Prescott Webb essentially launched his career, his academic career, in reaction to the Canales investigation. He wrote his 1922 Masters theses as an apology for the role of Rangers during this period and later transformed that piece into his hagiography of the Rangers, the 1935 Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, which is still a perennial best seller for the University of Texas Press.

What are some of the long-term consequences of the violence?

This event tremendously impacted the development of Mexican American civil rights organizations. During the 1920s Mexican Americans began to organize in new ways, in new kinds of political and civic organizations devoted to the promotion of Mexican American civil rights. The exemplary one from this period would be the League of United Latin American Citizens, which formed in 1929. LULAC emphasized the idea that Mexican Americans had to cement their political allegiance to the United States rather than to Mexico because the United States would be the nation that would protect them from any future violence directed against them. This was the cultural project of this civil rights organization.

This is a really fascinating history that people don’t know much about. You got involved because you’re part of a group that is putting on an exhibit about the Borderlands War at the Bullock Museum of Texas History, is that right? Can you tell us a little about that exhibit and what its purpose is?

The exhibit is called “Life on the Border, 1910-1920” and the purpose is to raise the public’s awareness of this incident and the major role it’s had in shaping Mexican American life in Texas. The role of the state in perpetrating this violence is something that we as a group have wanted specifically to highlight with this project with the goal of making connections with questions of policing communities of color, which are obviously relevant today.

We’re looking forward to that exhibit and you’re hoping to have the exhibit, after its run at the Bullock, travel around Texas to the Borderland region but also to the rest of Texas to bring this story to the population?

We’re hoping to take it nationally.

Even better.