With the establishment of Manila as a Spanish trading port in 1571, one of the most important economic links in the early modern world was established. Spanish silver flowed from the mines of Potosí (in modern Bolivia) through Manila to Ming-dynasty China. The interplay between these two empires created a global financial system that linked far flung parts of the world in a way that mirrors the 20th century phenomenon that has become known as “globalization.” Guest Ashley Dean just completed her doctorate in history at Emory University examining the impacts of this pre-modern trans-Pacific linkage whose far-reaching impact touched nearly every part of the globe.

Guests

- Ashleigh DeanAssistant Professor of History at Monmouth University

Hosts

Kristie Patricia FlanneryPostdoctoral Fellow, University of British Columbia

Kristie Patricia FlanneryPostdoctoral Fellow, University of British Columbia

We often think about globalization as something that is a quite a recent phenomenon. Some people would even say that globalization began in the late 20th century with the end of communism in Russia and the fall of the USSR, but you’re suggesting that this is actually a much older phenomenon.

Yeah, actually there’s a lot of historical evidence to suggest what when we have globalization, that is the linkages of all major continents in permeant trade networks, that this can date to 1571 with the establishment of Manila as a Spanish outpost in the Philippines. Now when we think of the Spanish we think of them exploring, colonizing, call it what you will, when we think of them establishing these new bases outside of Spain, we think of them being in support of what we call the three g’s: gold, God, and glory, and in various orders depending on who’s saying it. What’s actually more important in terms of metals, is silver, not gold.

Tell us about the world in the 16th century, so we can get a sense of what it was like before these new linkages were formed between the Americas and China.

Well in the 16th century there’s already been several decades of Transatlantic travel, trade, I don’t know if I want to say exploration, but European expansion I think would be a better way to describe it. We don’t have this happening in the Pacific. The best we have for the Pacific before this period, is that it’s quite likely that Polynesian people had traveled through a lot of the islands in the Pacific, they may even have made it to the American continents. There are persistent rumors that Chinese sailors did as well. It’s a historical controversy, but for the most part in this period, the Pacific ocean hasn’t been an aspect of this new rise in intercontinental trade and travel.

So in the Pacific in the mid 16th century, there’s this interesting thing, on one side, we have the Ming Empire which had been in power since 1368. It is a Han Chinese Empire, that is, it wasn’t China ruled under the Mongols as it was before, and the Ming Empire in this period traditionally historians thought of it as being in a period of decline in the 16th century. That view has changed in recent decades. The Ming are now considered to have been very powerful, very militarily advanced, and a major world power, if not the major world power in this period.

We have the Ming on this one side of the Pacific, and on the other side we have the Spanish Empire in the Americas, which has been established for several decades by the mid 16th century, and it’s part of an aggressive expansionist Spanish Empire which in this period that we’re talking about here of the silver trade, not only controls a large proportion of the Americas but a large amount of continental Europe as well. This control andwarfare in continual Europe is very important because its where Spanish finances are draining too. When we’re talking about the terrible state of Spanish finances, it’s because they’re spending everything on these incredibly ruinous wars on the European continent.

So silver drove the first globalization in the world?

Absolutely, and we tend to, and I think particularly when I was in high school, throughout most of the 20th century, we think of this as a European driven phenomenon, that it happens because these European powers are leaving Europe, colonizing new parts of the world and this colonization and this grabbing for gold, silver, and other precious metals, is what’s driving this. But what is actually driving this is a major reform in the Chinese tax system around the same time.

So tell us more about these changes.

This change is complicated, everything involving this is complicated. When we talk about Chinese money, Chinese currency, Chinese exchanges, one of the first things that comes up, is China is one of the first countries to invent paper currency. They’re very famous for this. The problem with having a paper currency is the eternal temptation to print up more of it, and this happens at the end of the Yuan dynasty and the beginning of the Ming dynasty. There’s serious inflation, there are financial problems and they start printing up more and more paper currency and people lose their faith in it, as happens everywhere. So what happens is that in China, they move from this paper currency to actually metals, and silver is one they’ve chosen, and the reasons for that are complicated and not fully understood I don’t think. What happens during the late Ming dynasty though is that there is a push from the center to reform the tax codes. This is called the Single Whip Reform, or in Chinese the Yi Tiao Bian Fa. In Ming China you’d pay a series of many different taxes and you would pay them in rice. The Yi Tiao Bian Fa, the single whip reform converts them all into one payment, and it converts that unit of payment from rice to silver.

So suddenly people who have been paying tax in rice have to pay those same taxes to the government in silver?

Absolutely, and in 1580, this becomes a law throughout the Ming Empire.

So I guess that means that China is looking for a source of silver then?

Yes, and in a fairly short period of time, China needs a tremendous amount of silver, and where they get this silver, they get this silver from two different places: Japan and Latin America.

So how does silver get from Latin America to Manila, and also actually maybe you can tell us a little bit about the silver mines in Latin America?

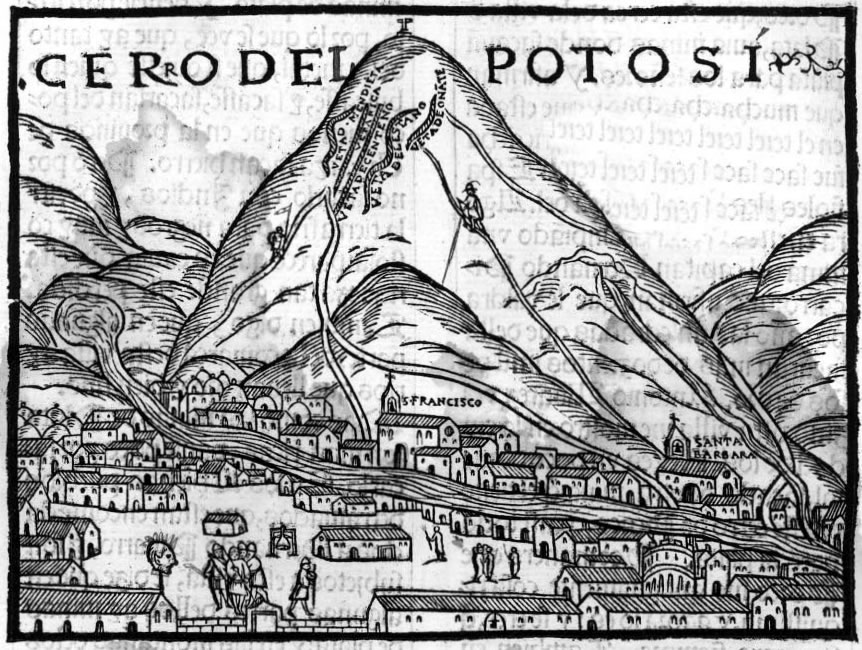

Yes. I was actually going to suggest we start with that. Well silver obviously comes from mines, and the most famous mine in this period is Potosí, in modern day Bolivia. This is a mine that is at an altitude of about 15000 feet. When this mine is discovered in the mid 16th century nobody was living there, but the Spanish imported mass amounts of people there. First they tried African slaves, and then they moved over to working Indians in these mines, to working indigenous people in these mines. I think the mines of Potosí can be considered one of the greatest human rights violations in Latin America history. The count for deaths at these mines in Potosí is about 8 million in this period.

Wow.

Just for some perspective, the mines are still operational today. Most of the silver is gone, but several thousand people still work in these mines. Today in 2016 with all our modern technology and medical advances, your life expectancy in those mines, you’re not going to make it past 35 or 40. It’s brutal, terrible work. Usually the miners die of lung diseases, accidents, that kind of thing. In the 16th century it was much worse. This silver that we’re talking about, one of the things that you always have to remember is that it comes at a terrible human cost.

So the mines at Potosí are the most important, there’s also mines in Mexico as well. What happens in these mines, how the silver gets from Potosí to China, is a trade route known as Manila Galleon. And this is a trade route that sails from Acapulco in Mexico to Manila and back once a year, one round trip a year, in the 16th century and early 17th century, twice a year, thereafter.

And how long did that take, because that is a very long way from Acapulco to Manila?

So first the silver has to be shipped from Bolivia to Acapulco, and that adds a tremendous amount of time in and of itself. Just the actual route itself, we actually have pretty decent records for how long that took. It’s very dependent on, first of all, individual factors like the weather, predation from pirates, Francis Drake was very well known for picking off returning Manila galleons in what’s now California. So it varies, we’re averaging for the period I study in the late 16th century, we’re averaging a return trip of, ignoring the fact that you typically will stay in Manila for a few months, it’s about 6-8 months total sailing time. And that can vary wildly. It’s much longer in the 16th and the 17th centuries because in that period, the return route goes much further north than does the late 17th and 18th century, so it’s a very long trip.

So the silver is coming from silver mines in Potosí and Mexico to Manila, how then is the silver moving to China?

Basically Manila is functioning as this giant trading post. There’s a very active trade with Chinese merchants in Manila, its the silver trade the trade between China and Spain, its very interesting trade. We think about Chinese trade in the pre modern period, we usually think of it in terms of tribute, of trade agreements. There’s actually no formal treaty between Spain and China in this period. They did have one with Portugal. They don’t have one with Spain, and this is a trade that’s very lucrative and very profitable, and a lot of my research examines why they don’t do this, and how this ends up falling apart, but, anyways I don’t know if that’s really relevant.

Could you tell us about the short term and longer term impacts of this silver flow that’s really flowing all the way from America through Manila to China. How is that changing people’s lives in both Asia and the Americas?

I think that you phrasing it as a short term and a long term question is very important because there are two very different outcomes. In the short term generally it’s quite good. For the first several decades after this trade begins, we have a tremendous amount of silver flowing into China. In return they’re getting not just the luxuries that we think of Europeans being interested in, silk that sort of thing, we also get gold from China that sails back to Mexico and then on to Spain. And in the short term this is very lucrative for both countries, for both empires. However, it doesn’t last.

Like I mentioned before there is a tremendous amount of silver pouring into China from not just Spain, but also from Japan. Over time, the amount of silver just becomes to much It becomes a glut on the market and the price of silver drops alarmingly, but all of these taxes and all of these wages are still being paid in silver, so it’s worth less. This leads in turn to more corruption, to less buying power, and in the long term it weakens the strength of both the Ming and the Qing dynasties. In Spain you have a very similar situation, except that as the value of silver drops the Spanish become less interested in trading silver with China, and when this trade kind of dwindles, it has a terrible effect on the Spanish finances, and in fact, Spanish finances in this period are generally terrible to begin with. The Spanish Empire had multiple bankruptcies even when the silver trade was at its most profitable. So in a lot of ways the silver trade is very much propping up this empire that’s financially in very bad shape to begin with and when that silver trade finally dwindles and lessens in scope, it’s very bad for Spain.

And what about some of the cultural consequences of this exchange?

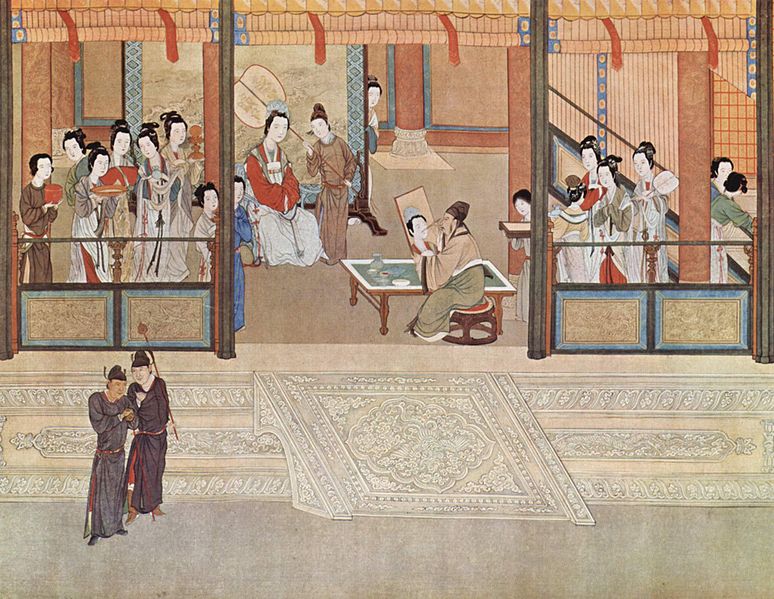

Well, when we talk about cultural consequences we look at it is as being something on both sides of this large Pacific world. In China, there’s this influx of silver. There’s a lot of debate over whether not it actually helps people on the ground in China long term, whether or not it actually helps the individual economic prospects of people. In terms of cultural exchange, it actually fosters this very wonderful exchange between China and Latin America, obviously Spain, of course. There’s an exchange for silver, they’re not only getting gold, they’re getting luxury items, they’re getting commodities, and what this does, is this spurs an industry in China of producing and shipping out these commodities for a Spanish audience.

So what kind of commodities are we talking about?

We have the typical, I guess the stereotypical things like silks, spices, you also have interestingly this growth in religious items. Icons, statuary, reliquary, that kind of thing. And a lot of these things are produced in China for an audience of Spaniards living in Latin America and in Spain, so you see these very interesting statues of the Virgin Mary, where she’s actually being painted and portrayed by a Chinese artist and she’s being portrayed in similar style to how they portrayed Guan Yin the Buddhist Bodhisattva of Mercy. So there’s a very interesting rise in Chinese produced luxury and religious items in Latin America.

Was there a similar flow of European or American goods going back to China?

Not as much, really. They mostly just want silver. Ming and Qing diplomacy at this time involves gifts and there’s this theatrical aspect of this presentation of luxury items from your home country. There’s not a huge trade in actual European goods until much later in the 19th century.

In the mid 16th century, we have China on one side of the Pacific Ocean, and on the other side is this transcontinental Spanish Empire, but they are very much separate.

Yes. They did not actually meet directly until the 1570s when the Spanish were able to establish Manila as a trade base.

Any ideas for wrap up questions? Do you want to go out with a bang? Shipwrecks? Pirates?

So much shipwrecking, so many pirates. Actually I was just reading some really interesting research, somebody went through and they counted every single Manila galleon that sailed in the 16th century and they calculated that the rate of shipwreck in this period is about 1/3.

I would not want to be on one of those.

No, never, not for your life, but actually piracy is a huge problem of both sides of the Pacific. I mentioned Francis Drake before, but in the Chinese sphere in the Pacific it’s a major issue because of these restrictions on formal trade, this informal trade, this piracy springs up, but it only gets worse as the Ming collapses.

So are we talking only European pirates?

No, no, no, Chinese pirates, Japanese pirates, Korean pirates, everybody could be a pirate.

Maybe you could wrap up by talking about why do you think this is an important kind of thing.

This is the first major transoceanic trade. This predates the rise of the slave trade, what we call now the triangular trade in the Atlantic. It actually in a lot of ways sets the stage for it, establishing that this is possible, this transcontinental, across the ocean trade is sustainable long term and ultimately at least in the short term, very profitable for both parties concerned.