There is no question that the idea of race has been a powerful driving force in American history since colonial times, but what exactly is race? How did it become the basis for the institution of slavery and the uneven power structure that in some ways still exists? How has the idea of what constitutes race changed over time, and how have whites, blacks (and others) adapted and reacted to such fluid definitions?

Guest Jacqueline Jones, one of the foremost experts on the history of racial history in the United States, helps us understand race and race relations by exposing some of its astonishing paradoxes from the earliest day to Obama’s America.

Guests

Jacqueline JonesWalter Prescott Webb Chair in History, Ideas and Mastin Gentry White Professor of Southern History in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Jacqueline JonesWalter Prescott Webb Chair in History, Ideas and Mastin Gentry White Professor of Southern History in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin

Hosts

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Joan NeubergerProfessor of History, University of Texas at Austin

Jackie Jones is a specialist in American history and she’s a regular contributor to Not Even Past. In fact her book was the first we featured when we started Not Even Past. She just published a new book called A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama’s America. (editor’s note: one of the New York Times’ 100 Best Books of 2013!).

Let’s start with the paradox that’s at the heart of the book. This is a book that’s founded on a paradox, that’s full of paradoxes. There’s no historical or biological basis for racial ideas, but the concept of race is at the center of American history and American life. And the use of race has become a tool for creating and promoting and maintaining power hierarchies, and yet, the first paradox is, before the American Revolution, you argue, slavery existed without any basis in race, or without ideas of race justifying it.

That’s right. The slave holders I looked at in 17th century Maryland and 18th century South Carolina were looking for the most efficient work forces they could find, and those happened to be Africans and people of African descent. In this Atlantic world of colliding empires, Africans were the most vulnerable. They did not have a nation state to rescue or redeem them, they did not command the high seas, and it was for this reason that Africans and their descendents were enslaved. The slaveholders I looked at did not talk about race; they did not use that as a reason for enslaving an entire group of people.

So then what happens when the American Constitution’s written? Why does that promote the need for racial ideas?

I think, actually going back a little earlier, during the American Revolution, we find Thomas Jefferson, the author of The Declaration of Independence, writing a book called Notes on the State of Virginia in 1781. It’s in that book that he begins to speculate about “natural,” or racial, differences between blacks and whites. I think he had to do that because he had to justify the fact that a whole group of men, men of African decent, were left out of the body politic. So there’s a paradox: the author of The Declaration of Independence was one of the first people to engage in what people today would call scientific racism. And he had to speculate about “natural” differences between the races in order to justify the exclusion of black men from rights.

Talk about paradoxes and contradictions! We just two months ago featured Denise Spellberg’s book that shows Thomas Jefferson using ideas of natural law to justify the inclusion of people of all religions, and now he’s using racial ideas to exclude some people from the body politic.

Well, we have to remember that Jefferson himself was a slaveholder, and when he describes the differences between blacks and whites — he says for instance that black people can work in very hot temperatures and very cold temperatures, black people can work without much in the way of sleep, black people don’t grieve over lost loved ones — these were all generalizations based on his self interest as a slaveholder. So we do see this myth of race is very much a product of its time and place.

All right, well let’s move forward a little in time then. After the Constitution codified slavery, many northern communities passed laws abolishing slavery, but at the same time they passed other legislation to exclude blacks from freely participating in the economy and also to limit their legal rights. You look at Providence, Rhode Island, how did that play out there?

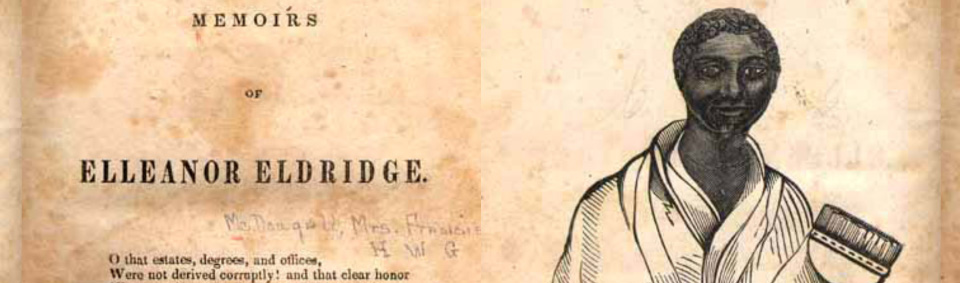

Yes, I looked at a savvy black businesswoman named Eleanor Elridge who revealed some of the contradictions during this period. This was a period in Northern history where black people were considered naturally poor and dependent. Many of them had been released from slavery with very little in the way of resources, and so were very poor. But at the same time in Providence there was an idea that black people were predatory, that they would not rest until they had taken the jobs of white people. This I think shows how contradictory this mythology of race can be in any one particular time and place, the idea that blacks are simultaneous very lazy, very dependent, and at the same time very ambitious, very aggressive, and very assertive, and wanting their rights and wanting jobs, and so on.

And Eldrige’s life really exemplifies that. She was an ambitious woman.

She was. She was a whitewasher, a painter, she was a laundress, and most of all she was a real estate investor. She accumulated money and invested in real estate, overextended herself, and found herself at the mercy of not only creditors, but also sheriffs and other local officials who really wanted to deprive her of her property. She belied the stereotype of the dependent African American and she relied at the same time on her patrons and her employers, otherwise she would have been totally at the mercy of whites who wanted her property.

So they could use her dependence on them to argue for her weakness and justify and explain away her ambition.

Well, she certainly needed patrons, and at the same time they could say that she was exceptional. So they could hold in their mind this stereotype, and at the same time they could acknowledge she was very different.

One of the areas later in American history, really throughout American history, where this contradiction plays out is in the area of education. So this myth develops that blacks, because of inherent natural weaknesses or flaws, can’t really learn. But at the same time communities felt the need to pass legislation to exclude them from education. How does that play in? You discuss an example in Mississippi in the early 20th century.

Yes, I think this is an interesting paradox: on the one hand whites claimed that black people cannot learn, and on the other hand they feel like they need to pass legislation to prevent black people from learning and going to school. Actually it was one northerner who said, “Black people will never be able to rise because of their natural limits. We should not permit them to rise here,” suggesting that it was going to take some legislation to keep them from going to school. It is a point that I make throughout the book, that a lot of discriminatory legislation actually reveals that white people know that black people are just like them. It’s kind of counterintuitive, but the legislation is to keep black people from doing what white people know all people want to do: to get an education for their kids, to live safe and secure lives, to get good jobs. So we think of this legislation as highlighting the differences between the races, but in fact it reveals the similarities between blacks and whites. And that is why whites were so eager to protect their own privileges and enact legislation to prevent blacks from sharing in those privileges.

Tell us about William Holtzclaw and his effort to open a school in Mississippi. What happens to him?

He was born in the late 19th century in Alabama, he went to Tuskegee Institute, which was run by Booker T Washington. Then Holtzclaw, himself, wanted to found his own small Tuskegee called the Utica Institute in Mississippi. He founded that school in 1903. And he lived in a period when white politicians were really demonizing black people, and especially black men, arguing that they were naturally aggressive and vicious. James K Bartleman, the governor at the time, argued that black people should have no schooling whatsoever. They should not learn to read or write, they should not get any industrial training, because they should stay as field workers their whole lives. And Holtzclaw, by opening this small industrial institute, really fought against that imperative. It’s a fascinating story how he had to navigate these extremely vicious politics at this time.

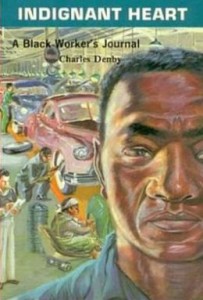

One of the things your book does really well is show how these ideas mutated to whatever situation they found themselves in. By the time we get to the late 20th century, leftist ideas enter into black politics to help challenge some of these contradictions. You tell a really fascinating story about Simon Owens, a black communist and labor activist. Tell us a little about him and what he was facing.

The premise of the book is that we have to look at these particular racial ideologies in a particular time and place. We can’t make sweeping generalizations about them throughout American history because they very much are contingent on the political economy of any time or place. Simon P. Owens is probably best known as Charles Denby, the author of an autobiography called The Indignant Heart, and his life too is full of contradictions. On the one hand, he was very progressive about the role of technology in industrial work places, and exploiting black and white men together; on the other hand, he argued against United Automobile Workers leaders and Socialist Workers Party leaders who argued that blacks were just a subset of the working class, and no one need pay attention to their unique history or unique vulnerabilities. So on the one hand he was very much class oriented and determined that the blacks and whites should march together into the future, aware of the devastating affects of these industrial technologies, on the other hand he was firmly convinced that black history was different and the black struggle should play a critical part in any kind of radical politics.

And he was facing the white labor force in the auto industry, where whites were working very hard to keep blacks from joining together in the kind of class solidarity that his Marxist ideology led him to think about.

Yes, he was frustrated because often the leaders of the UAW would come out with some very egalitarian pronouncements, but the social division of labor in the auto factories remained very much to the detriment of black workers. They were last hired, they worked in the most dangerous and arduous jobs, and many shop-floor stewards did not challenge that social division of labor. They kept blacks in these low paying, menial positions. That infuriated Owens. He found himself very much at odds with UAW stewards and leaders throughout his career.

I think one of the most powerful things about the book is that you show how these ideas about race continually morph in order to protect white privilege and white affluence and power. In your epilogue you talk about the recession of 2008 and how that has really impacted black and other minority communities much harsher than it has white communities.

Yes, it is obviously important that we realize that although race is a myth, the affects of the myth have been devastating and leave us with structural elements today, in American society. A couple of examples from the recession of 2008: historically black men and women have been disproportionally represented in public sector employment, but with the cutbacks at the local, state, and national level, after 2008 many of these public sector workers lost their jobs. Also, because of these predatory mortgage lenders, many black homeowners went into foreclosure.

That was a great example of the way the racial ideology changes. Earlier blacks had been unable to even get mortgages.

Under red-lining, yes! For many generations red lining kept middle-class blacks from owning their homes because they lived in “black” areas and banks said these areas are off limits. So it is a reverse now for these lenders to go in and make a point of finding the very most vulnerable people, offering them mortgages at very high interest rates, and then re-possessing their houses.

The other area where this really comes into play today is in the election of our first African American president. We generally tend to think that in history contradictions will correct themselves, or our ideologies will not be contradictory. But one thing this book shows is how these contradictions are unresolvable. So Obama challenges the stereotypes of the race myth with his Harvard education, his community service, his strong family, his unflappable demeanor, and yet this seems to have brought about some of the worst kind of virulent racist, irrational responses.

Right, so when we elected Obama in 2008 there was much rejoicing over the beginning of a so-called “post racial America.” The idea was if we elected a black president then we’ve overcome this past of racial mythologies and so forth. And that, of course, was just not true. For example, as I’ve already mentioned, the recession had a devastating effect on black families, disproportionate to white families. Secondly, yes in times of great economic stress, as I show throughout the book, black people are often identified as scapegoats. I think we might be seeing something here where Obama, as president, incurs the wrath of people from a different political party, people who are uncomfortable with the fact that the country is becoming more diverse. He’s sort of a proxy for a lot of changes that are happening in the United States today. But it is certainly not true that we can say we live in a color-blind society. I would never suggest that. The structural inequalities in housing, in education, in healthcare; these are very much the product of historical forces and they’re very much embedded in America today.

The product of historical forces based on the myth of race that the whole book is about.

One of the things I do is I try to get people to think about the way they use the word “race.” I suggest that by continuing to use the word “race” we make it concrete. We don’t mean to. Not many of use today would buy in to the idea that there are real racial differences in terms of a kind of biological determinism, but the fact of the matter is the terms race, racial relations, racial disparities, racial differences are used all the time and I’m afraid people don’t stop to think that by using the word they’re actually making it concrete in a way that it isn’t. And they know it isn’t as well.