Andrew Jackson’s presidency marked the introduction of a real maverick to the White House: a frontiersman from Tennessee, not part of the Washington elite, who brought the ideas of the people to the national government — or, at least that’s what his supporters claimed. But Jackson’s lasting political legacy instead comes from expanding the vote to all white males (not just landholder), and the tragic effects of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Guest Michelle Daneri from UT’s Department of History helps us sort through the political forces that brought Jackson to office, and the long lasting impact of his presidency.

Guests

Michelle DaneriNative and Indigenous Studies Scholar

Michelle DaneriNative and Indigenous Studies Scholar

Hosts

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Christopher RosePostdoctoral Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, The University of Texas at Austin

Today we’re going to be talking about the social impacts and legacies of the era of Andrew Jackson, who of course is one of the more infamous of our 19th century presidents. So remind us who Andrew Jackson was and how he came to politics.

Andrew Jackson is often remembered as a president of the people—incredibly popular and attuned to peoples needs and wants. This whole image rises up from how he first became famous, and that was because he was a war hero in the War of 1812. He was a major general and was hugely famous, especially after he won at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. After this point, he really would have been a household name. He would have been someone people know. This was a time when, during a big war, people knew these sorts of things. He definitely would have been a huge celebrity.

Also during his election campaign, he really worked on setting himself apart from presidents of the past. He wanted to show that he wasn’t one of these elites from the Northeast and New England. He was from the backcountry, he was a frontiersman. He was born in a cabin in Tennessee.

He wasn’t a part of the Washington elites.

Exactly! That rhetoric really comes out of today, but that’s how he tried to set himself apart. And this is really an ironic persona for many reasons, one being that he was incredibly wealthy. He owned a plantation with many, many slaves. He was one of the wealthiest people in America. So while he did have humble origins, for sure, he wasn’t just some guy that they found on the frontier and had him become president. So those are two reasons why he’d be remembered as a president of the people.

However, the third thing that he did that made him have more mass-appeal was that he extended the vote to nearly all white males. So this was a departure from voting being reserved for landholding people, and extended this perception that he cared about people and wanted more voices to be heard in Washington D.C.

I guess I don’t realize that, before that, it was only landholding males who could vote.

Yes. So, in a way it is arguably elite, obviously. He did extend the vote to more segments of the population, but obviously not everyone.

Ok, so now we’ve extended the vote to white males, but we’re clearly leaving out other segments of the population.

Yes, absolutely.

By 1840 ninety percent of white males could vote, but this of course left out a lot of people. I, for one, could think of women who would not be allowed to vote until the ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920. African Americans, despite their status of freedom (some were enslaved, some were not), did not have the right to vote, and arguably they didn’t until the passing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, when they were able to comfortably and consistently vote.

Also, Native Americans, who were not citizens of the United States, universally, until 1924 with the passing of the Indian Citizenship Act—before then, they were only citizens, universally, of their own tribal nations—and then in 1924, whether they wanted to or not, were extended US citizenship. Of course, today there are still people who can’t vote (such as felons, children, non-citizens). So clearly Jacksonian Democracy didn’t include everyone, it does extend those who are included, but it doesn’t cover everyone.

All right, so what was behind this expansion of the voting to more people, rather than just landholders. Was there some political interest behind it?

Well, it would have changed what political interests would have been, or what priority issues would have been. There have always been these tensions between white people who wanted to have land and native people. Earlier we see Bacon’s Rebellion happening between frontiers people, upset that the British government was siding with the Native People rather than them—and that’s something to remember: when these tensions are happening, and the United States had formally been a colony of the British, the British would have catered more to the needs of native people because they were seen as a diplomatic power that you want to have good relations with (otherwise they could side with the French, the Spanish, someone else). They had this diplomatic power that they won’t have by the time the United States is in power. Because the United States is the real imperial force in the area and they don’t have that same leeway.

So once the United States is in charge, once the newly implemented voters have a say, one of their top priority issues is going to be land acquisition. Even though people can vote without land, land is something you really need for status. Think about how important holding land, with those pastoral images for all Americans, it’s not a surprise that people who could now vote would want to have access to these desirable lands in the southeastern United States.

And we’re talking about the Southeast, as in the area that is now Florida?

We’re talking about the deep south, the Carolinas, Georgia, and such. So this area.

And also, by this point, we have the Louisiana Purchase, which was still being divided up, and of course the problem was there were people living there, even if we didn’t recognize them as citizens at the time.

Yes, absolutely. So even though the United States is pushing further west, there’s still this desire to take up ownership in parts that had already been a part of the US. So even though these areas in the southeast, that would have been owned by native peoples, are their own nations, there is a desirability to see that become part of the US—become lands that non-elite white people can have access to.

So, clearly we’re heading into an area with a bit of tension here, because we’ve got one group of people who claims they own the land (because they’d been living on it) and another group of people who have basically created a nation on top of it. So what role is Andrew Jackson playing in all of this? What is his opinion and how is he expressing it as the newly elected president of the United States?

Well, that is a very interesting question, and I’d like to set up a little bit about what Jackson’s past role had been with native people. So, one thing Jackson took part in before he became president was a prominent role in aggressing the Seminole people in Florida. This happens, of course, when Florida is still owned by the Spanish. The Seminole people were a group of native people who lived there and were largely seen as a threat to the American nation—especially because they were in this southern borderland where escaped slaves could possibly go to. The Seminole people were famed (or unique) for embracing into their membership these formally escaped slaves. So they were seen as this huge threat to slave owners, and that’s one reason why he invaded it. And this is really remembered as something very brutal; there are a lot of massacres that take place between Jackson and these people.

It’s kind of interesting that this aggression happens because, previously, Jackson had actually allied with native people in the war of 1812—as I had mentioned earlier, in the Battle of New Orleans. He had to round up a lot of people to fight with him, and a lot of those people were actually native people. So you see a real change in his attitude with native people somewhere in this period. But he’s definitely known as someone who doesn’t have positive feelings towards them; in fact, he has a very paternal attitude towards them. And you can look at political cartoons of the time that would portray him as this father figure to native people.

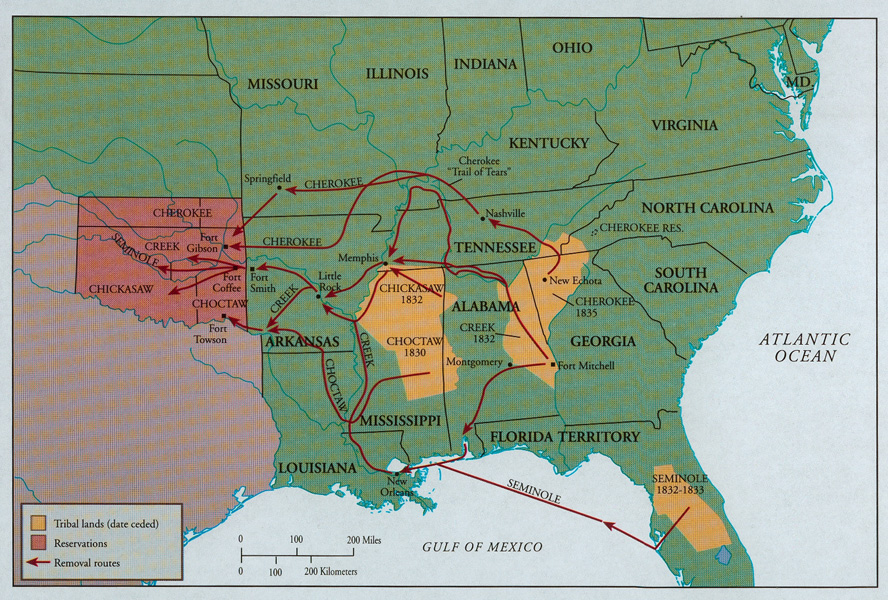

So by the time this issue of land acquisition comes up, and he’s newly president, he’s pushing forward this idea of the Indian Removal Act, which was framed as a voluntary migration of native people to Indian Territory, west of Mississippi. As you had mentioned, these land purchases that happened—migration would have pushed them even further west—west of the Mississippi into present day Oklahoma, a land where no one lived in at this time (but we’ll see that it, too, will also become desirable at some point).

It’s also interesting, as I mentioned earlier, this would have been a very favored move, but it did face some opposition. One sector of society that would have been really upset by this was Christian missionaries. They opposed this. Also, Davy Crockett. He’s a famous figure who also opposed it—so people who were more familiar with native people, who were a little more personally vested in their issues. It wasn’t this issue that everyone supported. People other than native people did oppose. However, ultimately we’ll see Indian Removal was not voluntary, and actually came out of a lot of violent coercion.

So, when was the Indian Removal Act actually passed?

1830. It authorized a voluntary migration of native people to federal lands in present day Oklahoma.

Ok: we’ve now mentioned two or three times that the Indian Removal Act was supposed to authorize voluntary migration, but it wasn’t voluntary if I’m not mistaken.

No, absolutely not. In practice it ended up being incredibly violent and coerce by the army. It was a forced removal of the Five Civilized Tribes, which were the Cherokee, the Chickasaw, the Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole peoples. And it would be absolutely devastating for them.

Why are they called the Five Civilized Tribes, out of curiosity?

Actually, that’s an interesting question. One of the reasons why was that a lot of these tribes owned slaves and practiced the same economic practices that other people practiced in the south. So it was this idea that they were a little bit more “white,” a little bit more “European;” they were civilized. If there was a scale of native people that went from “savage” to “civilized,” the Five Civilized Tribes were further up there.

Ok, so they were pretty much forcibly removed to the territory that is now Oklahoma.

They were forced tribe-by-tribe by the US Army, starting with 1831, that was the first forced removal. And it would continue until 1838 with the Cherokee.

What was that forced migration like for the people who went on it. And this is, if I’m not mistaken, what is popularly referred to as the “Trail of Tears,” correct?

Yes, that’s correct. That’s an important name for a reason. It really encapsulates the trauma and devastation that it caused.

I have a quote to read from Eliza Whitmore. She was age 5 when she experienced removal as a member of an enslaved family:

The aged, sick, and young children rode in the wagons, which carried provisions and bedding while others went on foot. The trip of was made in the dead of winter and many died from exposure to sleet and snow. And all who lived to make this trip, or had parents who made it, will long remember it as a bitter memory.

So this quote really is interesting for two reasons: one, is that Eliza Whitmore is part of an enslaved family—so we have to note that it wasn’t only indigenous people who were removed, there were slaves who also had to go with them. Another interesting point is that it’s something that people remember; it’s something that had a lasting effect. It was very traumatizing to have gone through this and truly devastating to be removed from your homeland—forcibly removed very, very far to these new lands that are desolate (even geographically/environmentally, nothing like where you lived before).

Right, we’re talking about slaves that were coming from the Deep South, which is sort of humid, forested, marshy, and they’re going to Oklahoma, which is basically grazing land, flat, plain, more extreme climate.

Yes, that’s correct. And that would actually create a whole slough of problems for the Five Civilized Tribes who were moved there. Once they get there, they’re encouraged by the US Government to practice agriculture. They end up devastating and exhausting the land, and the Dust Bowl ends up happening.* That’s largely framed as this chapter in the Great Depression where all these people from Oklahoma were removed (not “removed,” but economically forced out), but the kind of thing that gets talked about less is that a lot of these people were native people. So it’s kind like this whole pressure of moving west doesn’t even end with the Trail of Tears; again consequences pile up and you see people having to move to California during the Depression.

You’ve already mentioned that the Dust Bowl is sort of an indirect result of this forced migration of people who didn’t really know how to work that land after a couple of generations. What are the other lasting effects of the Trail of Tears migration?

Well one more commemorative aspect of it is people today continue to do pilgrimages to remember this certain chapter in native history. That may be walking pilgrimages, but there’re also motorcycle pilgrimages. It’s very interesting to see that people still find ways to commemorate and remember it.

And, as I had mentioned earlier about enslaved people being removed with the tribes, there would be lasting societal conflicts with these people who would eventually become freedmen in these societies. The question, at least for a lot of these groups, was how do they become incorporated after this? Do they get full citizenship? The US government mandates that they do, but of course that creates some societal tensions. Native people aren’t separate from the rest of society, and have some of the same ideas that mainstream society would have about race and difference. So they’re not exempt from the feeling that black people should be marginalized or not included, or somehow treated unequally. So you see that become a real challenge that continues to today with the Freedmen controversies. Some of these groups not wanting to acknowledge or extend membership to people who didn’t endure this experience that everyone had shared in. And it’s really a big part of who these people are today. It’s something that they collectively experienced, whether their origins can be traced back to being indigenous before exploration and colonization, or they were enslaved and made to experience this trauma along with the rest of the community.

Right. The other question that pops up into my head is: eventually Oklahoma became desirable land as well, even though these people had already been relocated there, so how did that work? Or did it work?

That’s fascinating because Oklahoma was originally selected as Indian Territory, and set aside for these people, because of its undesirability and its remoteness. “Oh, that’s way over there, west of the Mississippi, we’ll just put all these native people over there,” you know, “it’s not a problem.” However, we can think about the way the United States expanded past Oklahoma, that’s going to become desirable eventually, and it does. When people are pushing west there’s another newfound pressure, by the late 19th century, to open up these lands for white settlement. What ends up happening is something called “land runs.”

What ended up happening was they cut Indian Territory in half—so people now have half of Oklahoma, pushed into a smaller allotments and reservations, and were systematically given less desirable land—and the other half was opened up to settlers. What they would do would be to have all these people lined up, stand in a line, shoot a gun, and they would all run to claim land. So the trail of tears, and Indian Removal, wouldn’t mark the end of people consistently loosing land and being undermined by our larger national government. That continues as their land always becomes desirable in one way or another.

And, as we mentioned in the beginning of this episode, they wouldn’t even be able to claim citizenship until 1924, was it?

Yes, that’s correct. That’s something important to notice because while different segments of the population can vote, native people don’t have that voting voice that other people would have. It’s difficult.

And, of course, we can see some of these issues playing out even today with migrant workers and different issues having to do with sovereignty on reservations in the western United States.

Yes, absolutely problems are still ongoing. And problems become really complicated, too, during the 50’s. The United States government starts terminating the tribal sovereign status of groups, meaning, “we’re just going to incorporate them into the rest of the United States and it’s going to be great for them. They’ll progress like the rest of us.” However, the real effect of that is people in reservations, native groups, lose the communal holding of land. Land gets owned by individuals, and individuals can easily be swindled, or even economically motivated, to sell their lands.

That again is another way in which the lands of native people are slowly chipped away at. It’s something that definitely continues today. It’s something that people try to push back against—one group that comes to me is the Coast Miwok in northern California only have one scare mile left, but it’s something they’re holding on to because they don’t want to lose it. Land is really important to native identity and tribal sovereignty.